In December 1991 the USSR collapsed – a geopolitical catastrophe with deep consequences for the people of the Soviet Union, for China and for the world. I was in Moscow when this announcement was made – for reasons which were connected not only with the Soviet Union and the West but also with China, as will be explained below. At the beginning of 1992 I received an invitation to come to Moscow to write on Russia’s economy and for eight years afterwards I lived there with a goal to attempt to persuade Russia to learn from China’s economic reform instead of following the catastrophe of “shock therapy” – although at that time I had no direct contact with China. I therefore witnessed at first hand the consequences of the disintegration of the USSR and the restoration of capitalism in Russia – which was what produced the geopolitical disaster of the Soviet Union’s disintegration.

Seeing not in newspapers but personally such events naturally made the deepest impression not only intellectually but emotionally. More precisely they gave indelible images of what a geopolitical catastrophe means not merely in statistics but for the lives of ordinary people.

But simultaneously with these experiences in Russia I had been following China’s national rejuvenation from outside for decades, and from 2009 onwards I have worked in China. I therefore came to have first-hand experience not only of the collapse of the USSR and its consequences, but the rise of China’s national rejuvenation – it is almost impossible to imagine such contrasting experiences. In the collapse of the USSR, I witnessed a deep national tragedy. Since working in China I have seen the exact reverse, the rise of the Chinese nation and the development of socialism. For reasons which will become clear these processes were interconnected.

As people in China, fortunately, have not seen at first-hand what a geopolitical catastrophe and the restoration of capitalism means I hope readers will forgive me presenting here not only objective information and “dry statistics” but also first-hand experiences because these may make it easier to understand, and give a more vivid view, of these processes. The contrast of what I witnessed in Russia with the collapse of the USSR, compared to the advance in China’s national rejuvenation, which I had followed for decades in theory, and since 2009 witnessed at first hand, could not be greater.

The conclusion is clear and simple both from the objective facts and the personal experiences. The Chinese people have seen within China, from their own lives, the positive achievements in national rejuvenation led by the CPC. Although I am not Chinese, and therefore could not experience that achievement in the same way, I had the personal experience to analyse and see at first hand not only the consequences of China’s national rejuvenation led by the CPC, but also the disastrous consequences of the restoration of capitalism in Russia and the USSR. It might be said from that angle, it creates the deepest appreciation of how “lucky” China was to have the leadership of the CPC – except it was not “luck” at all, it was the extraordinary achievement of the Chinese people and the Communist political party it created.

The objective role of the USSR

First, it is necessary to make an overall balance sheet of the USSR. This is overwhelmingly positive – whatever was the final outcome in 1991. Furthermore, that balance sheet was positive not only for the people of the USSR itself but for the world.

The Russian revolution of 1917 created history’s first socialist state, it achieved gigantic steps forward in education and literacy for the Soviet people, in its early period it took the USSR from a relatively backward country to the second largest economic power in the world, that state defeated German Nazism saving Europe from fascism, its impact was decisive in the destruction of the colonial Empires, the fear of spread of the Russian revolution led to capitalism in Western Europe creating a system of social protection for the population. For China, of course, the Russian Revolution played a key role in its national destiny leading to the creation of the Communist Party of the China (CPC) and therefore of the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. As Mao Zedong stated, without the existence of the USSR the creation of the People’s Republic of China would not have occurred. These, and many other accomplishments, mean that whatever then occurred the achievements of the USSR were a gigantic contribution to both its own people and the entire world.

Given the enormous positive effect of its creation, the fall of the USSR entirely predictably unleashed a whole series of extremely negative global trends. Within the former USSR it led to the greatest peacetime economic decline in world history, internationally it unleashed a period of reaction in the imperialist countries and many semi-colonial countries which has lasted until today, removal of the fear of the powerful USSR led to the US unleashing numerous aggressive wars in Iraq, the former Yugoslavia, Libya and other countries. NATO advanced aggressively into the former USSR – forcing Russia to engage in a struggle against severe threats to itself which continues until today. In short not only the people of the former USSR suffered from its collapse, but it had powerful negative consequences for the world.

What the consequences of the collapse of the USSR meant in human terms

Turning from these fundamental historical facts to their connection to purely personal experience, it was because it was possible to analyse both the fundamental significance of the rise of the USSR, and therefore foresee in advance negative consequences of its collapse, that I was in Moscow in December 1991. Faced with such fundamental events it was a duty to attempt to do anything at all possible to fight against this.

But by 1991 I also knew something else. There was a positive alternative to the foreseeable disaster that was unfolding in the USSR – this was China’s enormous success and achievements. This was why I was already concentrating on a comparison of China’s successful “economic reform and opening up” to the foreseeable disaster, first, of Gorbachev’s policies in the USSR and then of the shock therapy course proposed for Russia. My first newspaper articles on this were published in Russian in January 1992 and then a more fundamental article, finished in April 1992, was “Why the economic reform succeeded in China and will fail in Russia and Eastern Europe” – also originally published in Russian. Later I had the honour to have my economic writings distributed to all members of the Russian Congress of People’s Deputies by order of the chair of the Russian Parliament. I had the honour to know patriots and socialists in Russia who fought against the disaster unfolding in their country.

But, of course, shock therapy was not reversed – capitalism was restored in Russia. This led to some of the most terrible things I have ever seen in my life – a warning to what the people of China would suffer if capitalism was restored there. Russia suffered the greatest economic collapse in peacetime in world history – from 1991-98 Russia’s GDP fell by 40%. Male life expectancy fell by six years between 1991 and 1994.

As I was in Moscow when the dissolution of the USSR was announced I saw the effect this had on the people I was staying with. They were stunned that it was announced that their country, the Soviet Union, was to be disintegrated. To make a comparison imagine the impact for the Chinese people if it was announced that the whole of China was to be split up?

Transferred from these huge social facts into purely human experiences, literally thousands of pensioners began to line the streets, in the bitterly cold temperatures of a Russian winter, trying to sell pies or cakes they had baked in their homes, or not even a pack of cigarettes but a single cigarette – this last is no exaggeration, I saw it with my own eyes. Wars began on the territory of the former USSR – particularly between Armenia and Azerbaijan and then in Chechnya. The military conflict taking place in Ukraine today is a further continuation of this process.

Direct personal experiences

To turn from what I witnessed to purely individual experiences I may give just a few of my most harrowing memories which characterised that period. I was hiring a room in a building to do my writing work. I noticed that as I came into the building each day the person who looked after the door seemed to be living in a single room with his wife and children – with no separate toilet, no kitchen or anything. As he helped me, I paid him some money for this help. He came to my office almost in tears explaining he had had to flee the war between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and he was so grateful to me – I was embarrassed because I could do so little. Later I found a place to live with a Russian couple and their adult daughter – both the parents died within a year, I am sure in part, because there was no adequate medical treatment.

Such treatment of people would be anti-human under any conditions, but it had an even greater significance for anyone who knew history. These pensioners were the generation which had defeated German Nazism at the cost of 27 million people dead in the USSR. They had saved Europe and humanity from German Nazism. It was a great duty of the state to ensure that they lived out their old age with the greatest possible support.

But instead of this the new Russian comprador capitalist class showed its totally anti-human and anti-national character. Because they made the mistake of believing as a foreigner I would support them, the new capitalists openly declared their views to me. I was told not once but several times that if old people “could not adjust to the capitalist economy then they should die”. It was explained to me that it would have been a good thing if Hitler had won the war against the Soviet Union as capitalism would have been introduced earlier.

To take a particularly graphic example, May 9, the anniversary of the defeat of Hitler, is the most solemn day in the Russian calendar due to the enormous sacrifices of the Soviet people in defeating Nazism. In addition to the official parades for obvious reasons on that day light entertainment, frivolous parties etc are not attended. Sections of the new capitalists therefore on that day deliberately organised parties, theatre visits etc to show their contempt for the struggle of the Soviet people against Nazism. This would be equivalent in China to some people choosing to mark 13 December, the memorial of the Nanjing massacre, by throwing light-hearted parties or trivial entertainment – a deliberate anti-national insult to the suffering, sacrifices and heroism of the Chinese people.

Given these experiences in Russia when I came to China in 2009, I was not surprised to find not only patriotic capitalists but also comprador capitalists who made the same mistake as in Russia of believing that because I was a foreigner, I must support them. So, they told me of their ambitions that capitalism should triumph in China, that the US was a superior country to China, therefore of why they were investing in the US instead of their own country etc. It was a simple echo of what I had heard from similar forces in Russia – not a surpise but a personally significant confirmation and experience.

Failure of the USSR

To return from these personal experiences to the more important issue of objective trends it is of course necessary to understand what forces led to the collapse of the USSR and, in sharp contrast, to the success of China. Given the enormously different outcomes this is the most fundamental question of the last part of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st centuries.

The USSR in its early years faced an entirely different global situation to China today or at the time of China’s launching of “reform and opening up” in 1978. In 1929, only 12 years after the Russian revolution, and 7 years after the legal creation of the Soviet Union, the greatest economic crisis in the history of capitalism broke out – the Great Depression. International trade and investment collapsed, fragmenting the world economy into a series of competing and relatively isolated blocs. The depression destabilised the entire world capitalist system unleashing the most reactionary forces – Japanese militarists began their aggression against China in 1931, Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933.

How to protect the USSR from the threat of external military attack and fascism therefore became the most vital question facing the Soviet Union. To deal with this, in 1929, with the first Five Year Plan and the collectivisation of agriculture, the USSR created an economic system never before seen in history. This was an economy which had only small amounts of foreign trade, and was therefore relatively isolated from the world economy, in which agriculture was collectivised, in which almost all the urban economy was state owned down to small shops, in which the priority was given to heavy industry, and above all military industry. The result was that from 1929-1940, the last year before the Nazi attack on the Soviet Union, the USSR achieved an annual economic growth rate of 5.3%, the fastest of any major economy – for comparison in that period Japan’s annual average growth rate was 4.6%, Germany’s 3.4%, and the US’s 0.9%.

The heavy military industry created by the USSR in this period provided the basis to win the war against German Nazism – thereby saving Europe from fascism. This success then heavily influenced other countries. The People’s Republic of China, in its first Five Year Plan, and in a more general sense up to 1978, was heavily influenced by this Soviet model – with the statification of most of the economy and with the People’s Commune movement the collectivisation of agriculture. But the USSR also affected even capitalist countries such as India. Certainly, in the 1950s and 1960s this Soviet economic structure was taken as the most followed “model” of socialism.

Soviet failure in economic competition after World War II

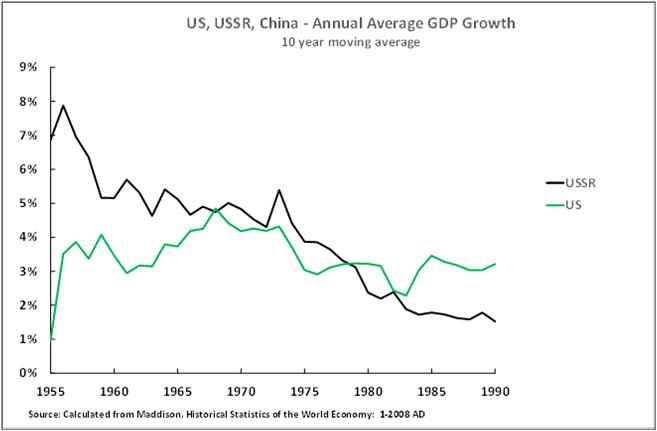

But after World War II this Soviet economic system was a relative failure in international economic terms. From 1950-70 the USSR’s economic growth ranked only 59th out of 142 countries for which there is data. That is, underperformance of the Soviet economy did not begin only in the 1970s, as is sometimes thought, it began throughout the entire period from 1950 onwards. Furthermore, in the new globalised post-World War II economy, which was in contrast to the self-enclosed relatively autarchic economies of the 1930s, major capitalist countries grew more rapidly not only than the USSR during that period but also of the USSR in the 1930s. As already noted, in 1929-40 the USSR’s economy grew at an average annual 5.3%, but in 1950-70 Germany’s economy grew at an annual average 6.0% and Japan by an annual average 9.6%. By 1950-1978 the USSR ranked only 83rd in the world in terms of economic growth in that period – not even in the top half. By the mid-1970s even the US economy, which had grown much more slowly than Germany or Japan during the immediate post-war World War period, was growing more rapidly than the USSR – as shown in Figure 1.

In summary in the several decades of economic competition after World War II the USSR’s economic system was a relative failure. This economic failure in turn led to a deep crisis in the USSR, creating the context for the disastrous policies of Gorbachev, and culminated finally in 1991 in the restoration of capitalism in the Soviet Union and the geopolitical catastrophe for Russia of the disintegration of the USSR. It was this economic failure which led to the restoration of capitalism and the national catastrophe of the collapse of the USSR – and it was China’s economic success which underlay its development of socialism and its national rejuvenation.

Figure 1

China’s success

Of course, in contrast to this economic failure of the USSR China after 1978 achieved literally unprecedented economic success – the most rapid longer than four-decade growth in a major economy in world history. By 1990, the last year of the USSR, China’s GDP had grown by 767% from 1950 – compared to 299% for the US, 290% for the USSR, and 409% for the world average. Updating to the present, from 1978 to 2020 China’s economy grew by 3,914% compared to 231% for the US and a world average of 180%.

In short, whereas by the mid-1970s the USSR’s economy was entering a crisis which finally resulted in its collapse, China was advancing to the most successful economic system seen in world history. It was this new economic policy and structure after 1978 which allowed China not only to avoid the economic failure of the USSR by the 1970s but to grow far more rapidly than any major capitalist economy. But in that case, what explained the extraordinary economic success of China and the economic failure of the post-war USSR? It was this which led to why I was in Moscow in December 1991 and witnessed the final disintegration of the USSR.

Not in line with Marx

The answer to the question of why the post-World War II Soviet economy was a relative failure, and of the post-1978 success of China, lies in the most fundamental analyses of Marxism – this is what made it possible to foresee both developments in advance. As these issues are absolutely fundamental for what took place in both the USSR and China it is necessary to briefly summarise them. They may initially appear as abstract questions of Marxist theory, but as will be seen they have the most powerful possible practical consequences in determining the ultimate collapse of the USSR and China’s success. Analysing them also allows a clear understanding of the enormous achievements of the CPC. (Much less significantly it also explains why I was in Moscow in December 1991).

Marx’s analysis, from the first formulation of historical materialism in The German Ideology through to Das Kapital and his last works, was that human and economic development was based on the increasing socialisation of labour. Indeed, the very word “socialism” derives from “socialised” labour and production. In Marx’s analysis each mode of production saw a greater socialisation of labour than the one before, until finally the enormous socialisation of labour in large scale capitalist production produced the preconditions and necessity of socialism.

Regarding this last phase, of the transition from capitalism to socialism, in the famous words of Marx, in the 32nd chapter of Das Kapital on “The historical tendency of capitalist accumulation”: “Hand in hand with this centralisation, or this expropriation of many capitalists by few, develop, on an ever-extending scale, the cooperative form of the labour process, the conscious technical application of science, the methodical cultivation of the soil, the transformation of the instruments of labour into instruments of labour only usable in common, the economising of all means of production by their use as means of production of combined, socialised labour, the entanglement of all peoples in the net of the world market, and with this, the international character of the capitalistic regime…. The monopoly of capital becomes a fetter upon the mode of production, which has sprung up and flourished along with, and under it. Centralisation of the means of production and socialisation of labour at last reach a point where they become incompatible with their capitalist integument. This integument is burst asunder. The knell of capitalist private property sounds. The expropriators are expropriated.”

Several immediate conclusions flow from this analysis by Marx of the increasing socialisation of labour and production:

- Large scale socialised production is the foundation on which capitalism is overcome – such large-scale socialised production should be “expropriated”, that is it should be in the socialised/state sector of the economy.

- The largest scale socialised production is necessarily international.

- As analysed in detail in Das Kapital, increasing “socialisation of labour” does not only apply to labour produced at the same point in time, a “geographical” concept of socialisation of labour, but it means increasing use of labour produced in previous production cycles – that is, in economic terms, an increasing role of fixed investment in the economy, or historical socialisation of labour. This is analysed by Marx in Das Kapital in terms of the increasing “organic composition” of capital.

- This process of socialisation of labour and production is inevitably uneven in its development – some sectors of the economy will be based on very large-scale socialised production considerably in time before such large-scale socialisation exists across the entire economy. That is, while large scale socialised labour and production exists in in some sectors, in others production will still be based on much less socialised production. The necessity of expropriation of these sectors of the economy based on much less large-scale socialised production therefore does not follow from Marx’s criteria.

- Factually agriculture lags behind urban production in development of socialisation of labour – i.e there will be relatively non-socialised production in agriculture and small-scale urban production.

The structure of the economy in the first stage of the development of socialism

The economic structure of the first stages of socialist development which flows from the analysis of Marx above is clear.

- Large scale socialised production should be in the socialist/state sector.

- This large-scale socialised production must participate in international production.

- There will be a relatively less socialised production sectors, in particular in agriculture and parts of urban production – which therefore do not need to be in the state sector.

This is, indeed, the economic structure during the initial stage of socialism which Marx outlined in the Communist Manifesto, the Critique of the Gotha Programme and other works – the relevant quotations from Marx are given in “The international and historical significance of the resolution on the history of the CPC”. Given I specialised in the international economy and economic theory these theoretical points by Marx were clear. In 1972 for the first time, I studied the Soviet economy within the framework of the international economy. It was immediately obvious that the Soviet economy did not correspond to this analysis of Marx. Certainly, in the USSR large scale socialised industry was in the state sector but:

- Instead of participating in the largest scale socialised production, that is international production, the USSR was building a largely self-contained economy – therefore cutting itself off from the largest scale of socialised production.

- Not only was large scale socialised production in the state sector, but far smaller scale, relatively non-socialised production, was in the state sector – something not called for in Marx’s analysis. In particular agriculture, and smaller scale urban production, was in the state sector. In Marxist terms, instead of the base determining the superstructure, that is the economic relations of production determining the legal forms of ownership, legal forms of ownership, state ownership, were being imposed on the economic base.

- Therefore, while the 1929-40 total statification of the Soviet economy, and its relatively autarchic character, might have been necessary for short term military purposes, in economic terms its continuation into the post-World War II period was an ultra-left deviation from Marx.

The conclusions which followed from that were therefore also clear.

- Because it was a deviation from Marx’s analysis in terms of long-term economic growth the Soviet model would be unsuccessful.

- It was required for the Soviet economy to begin to participate in the international economy.

- The collectivisation of agriculture was a mistake in long term economic terms, as was taking smaller scale urban production into the state sector – that is, agriculture should be decollectivized, and non-large scale urban production should be released from the state sector.

China and Gorbachev

I have no wish to exaggerate at all. At that time, I only studied the USSR, I did not study China. These conclusions formed in 1972 I thought had no possibility of practical application whatever and they occupied about 1% of my practical time. They were simply clear conclusions from economic theory.

But from 1978 onwards something quite new happened. China’s “reform and opening up” did not privatise the largest scale socialised production, it remained in the state sector, but it began to orientate China towards the world economy, introduction of the household responsibility system meant the decollectivisation of agriculture, the creation of non-state urban sector began etc. It was obvious, from the point of view of the economic analysis following from Marx, that this should be extremely successful. And if it was not then my understanding of Marx was wrong and needed to be changed! Either way I had to pay attention to what was happening in China.

Factually the issue was resolved very rapidly. By, say, 1981 it was already clear that China’s “reform and opening up” was a tremendous success. So that solved the issue on the positive side. Again, I do not want to make any exaggeration. As I never imagined that I could ever have any real connection with China. I just simply admired what was being done. Let us say it advanced to taking up 5% of my time.

Then in 1985 something very dramatic and negative began to happen. Gorbachev became General Secretary of the CPSU and from the point of view of Marxist analysis everything he did in the economy was the exact opposite of what needed to be done.

- It became rapidly clear that the privatisation of large-scale socialised production was being prepared.

- The USSR was not being oriented to competition in the global economy – that is it was not being oriented to the largest scale socialisation of labour.

- There was no move towards the decollectivisation of agriculture.

Therefore, the same analysis of Marx analysis which led to the view that China’s “reform and opening up” would be a great success led to the conclusion that Gorbachev’s policy would be a great disaster. From 1985 onwards, therefore, two perspectives opened out – success of China and failure of Gorbachev.

How I came to be in Moscow in December 1991

From 1985 onwards these issues relating to China and the USSR took up more and more of my time. As I never imagined I could have contact with China, I focussed on opposing Gorbachev’s policies in the USSR and his capitulation to Western capitalist attacks on the Soviet Union – first writing from outside Russia and then when it became possible, in late 1991, by going to Moscow. At the same time, I began to study not only the most fundamental features of China’s economic reform, which could be analysed from 1978, but the material that was available in English on the detailed economic discussions in China.[*] Finally, when I moved to Moscow in late 1991/early 1992, I could study Russia’s economy in more detail – all of which culminated in newspaper articles and then in April 1992 my analysis “Why the Economic Reform Succeeded in China and Will Fail in Russia and Eastern Europe”. All these had the clear analysis, self-explanatory from the title of that article, that China’s economic reform and opening up would be a tremendous success and that Russia’s shock therapy would be a disaster.

Through the media this work had some impact – for example I had a public personal exchange with the country’s Vice President, my economic analysis was circulated to all members of the Russian Parliament by order of its chair, I had a public debate with the President’s economic adviser at the invitation of the speaker of the Upper House of the Russian Parliament. Very much more powerful and important was, of course, the activity of Russian patriots and socialists who were fighting against the unfolding national catastrophe.

Russia’s patriots and socialists

Finally, so far, an analysis has been made of the great positive objective significance of the creation of the USSR, of the extremely negative trends unleashed by its fall, of the gigantic economic collapse unleashed by the restoration of capitalism in Russia, by the social suffering this imposed on the Russian people as a result, and of the outbreak of wars and ethnic conflicts as a result of the disintegration of the USSR. All the latter were hugely negative. I believe all these negative lessons are important as showing China what would be its fate if capitalism were restored. But amid this unfolding disaster there were lessons of a different positive type which were also crucial and left the profoundest impression.

In that time, I was in Russia I had the honour to meet Russian patriots, socialists and Communists who fought relentlessly to save their country from an unfolding disaster. These were people who were prepared to do anything, if necessary to give their lives, to fight for their country and for socialism. I mean that quite literally. There were several final attempts to try to turn back the tide of disaster that was unfolding in Russia under Yeltsin after 1991. This culminated in October 1993 when Yeltsin ordered tanks to attack the Russian Parliament which had been opposing the worst excesses of shock therapy – a military attack to suppress an elected Parliament which was cheered on by the farcically so called Western “democracies”. Russian patriots and socialists were killed by tanks and machine guns as they tried to stop that attack in the most severe armed clash in Moscow since 1917. They showed they were literally prepared to give their lives to try to prevent the disaster unfolding in their country.

These patriotic and socialist forces were in personal determination and courage on exactly the same level as the patriots and communists of China or every other country. That is why I said it was an honour in the most literal sense to know them. But China’s patriots and socialists had one thing these inspiring Russians did not have. This was the CPC.

This was a lesson which I had understood theoretically, but which my experience in Russia around the disintegration of the USSR turned into a deep emotional impact. The errors of the CPSU after World War II had led to the policies of Gorbachev. Once his catastrophic policies had been unleashed, culminating in the victory of Yeltsin and the restoration of capitalism, it was impossible for even the most heroic and self-sacrificing Russian patriots and communists to create together fast enough a force capable of preventing disaster for their country. In contrast, in China the policies of the CPC, not only prior to 1978 but in its reform and opening up after 1978, not only saved China from catastrophe but created the greatest economic and social successes in human history.

Reduced to the single most essential point the difference between national disaster in the USSR, and national rejuvenation in China, was the difference between the errors and then degeneration of the CPSU and the success of the CPC. Both the objective facts and the personal experiences I have tried to share in this article were, in the last analysis, the results of this success of the CPC and the failure of the CPSU.

Theoretical issues

Because not merely analysing but seeing at first hand the consequences of the disintegration of the USSR had the profoundest impact on me, in particular compared to seeing the rise of China, I think it is worth to summarise these conclusions in a few conclusions which flowed from these facts.

First, is the incredible power of Marxism – or in the famous phrase “Marxism is powerful because it is true”. It was possible to predict the fundamental trend of events in both the USSR and China in advance because, indeed, it was in fact predicted – not, of course, in all details or exact timescales, but in the most powerful and determining trends. Issues which appeared only as abstract theoretical questions of Marxism in the early 1970s became, by the late 1970s and 1980s, clearly the most powerful trends determining the completely opposite development of the USSR and China – negative in the former case and positive in China’s. Then, in the 1990s, it equally enabled prediction in advance of the catastrophe of shock therapy and the success of China. The test of science is that it predicts the facts of reality. Marxism did precisely that.

Second, linked to the first point, is the extraordinary achievements not only in practice but in theory of the CPC. Already in 1949, the CPC had achieved something unprecedented. Certainly, Lenin in 1917 had shown how socialism could be created in an imperialist country – rightly creating “Marxism-Leninism”. But it was the CPC, led by Mao Zedong, which for the first time in history in 1949 showed how socialism could be created in a developing country – establishing Mao Zedong, with Lenin, as the greatest political thinker of the 20th century and “Mao Zedong Thought”, as it is known in China, as a fundamental contribution to Marxism.

Third, having already created this extraordinary accomplishment in 1949, from 1978 the CPC then carried out a second great revolution both in practical results and in Marxist thinking. The USSR failed in the post war period because it failed economically – as has been analysed. The USSR’s economic structure, successful in the military struggle against Nazism, failed in the long-term economic competition with post-World War II capitalism. It failed because, as already analysed, it was in economics not in line with Marx. In 1978, with “reform and opening up”, China moved to an economic system that was simultaneously in line with Marx in theory but which in practice was unprecedented in world history. To understand the profound character of this, in the last 500 years, only three fundamental economic systems have ever existed – the capitalist system, which was not a product of any theory but was first analysed by Smith and Marx, the “administered” essentially 100% statified model introduced by Stalin in the USSR in 1929, and the “socialist market economy” of China after 1978. It is this latter system which has proved the most successful in world history.

This was a stunning achievement not only in practice but in theory – perhaps it helps to be an economist to understand just how enormous this achievement was, but everyone can feel its practical impact! The consequences of this transformed the world. Deng Xiaoping, Chun Yun and the others who achieved this did so, in the first place, for China’s national rejuvenation but in so doing they also saved world socialism – precisely in comparison to the collapse of the USSR. This has become profoundly understood by the Russian patriots and socialists who I had the honour to meet because they understood what the enormous stakes for their own country were. As Gennady Zyuganov, leader of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, noted in 2008 regarding China’s policy of reform and opening up: “Had we learned from the success of China earlier, the Soviet Union would not have dissolved.”

The fate of two enormous countries, in the negative for the USSR and in the positive for China, was therefore decided by the genius of China’s economic reform and the failure of the CPSU. All the great patriotism, support for socialism, and heroism of those I saw fighting for their country in Russa could not compensate for the fact that on these fundamental economic issues the CPC was correct, and the CPSU was wrong. It showed in the most direct terms that history is determined by the most powerful forces within it and an understanding of them as analysed by Marxism, and by the creation of organisations based on this – precisely of the type of the CPC. Individuals, no matter how much their moral qualities are equal to those of any other country, cannot substitute for this but must build organisations based on Marxism – something which cannot be achieved quickly but only by great effort, precisely as the CPC was created by the great struggles of the Chinese people.

These experiences also showed how important it was to have a precise analysis of the situation – which only a political party can achieve. The error of “rightest” deviations from Marxism, that is adaptation to capitalism, are well known. But it also became clear that “ultra-leftist” deviations were deeply, and potentially fatally, damaging. In China the recent “Resolution on the Major Achievements and Historical Experience of the Party over the Past Century” notes the errors of “Great Leap Forward and the people’s commune movement” as well as the “catastrophic Cultural Revolution”. Fortunately, the CPC corrected these errors. But while from the 1950s the CPSU moved geopolitically to “the right”, including Khrushchev inaugurating attacks on China, economically the Soviet Union never corrected the “ultra-leftist” errors in its economic structure, leading to the economic failure of the USSR and its ultimate collapse. This was a deep lesson to see dramatically that “ultra-leftism” could lead to as great a disaster as “rightism”. Only a precise analysis of the situation could be successful – and only Marxism made this possible

Third, was to see how these most powerful social forces, analysed by Marxism, were translated into the personal lives of human beings and the fate of a nation. The pensioners I saw standing on the streets for hours in the freezing Russian winter trying to sell a pie or a single cigarette, the person living in a single room with this wife and children because they had to flee the Armenia-Azerbaijan war, those killed by Yeltsin’s tanks for attempting to defend the Russian people and their own country. These were the victims of the process that led to the collapse of the USSR. I saw simply individual examples of a process which affected hundreds of millions of people.

Contact with China

Turning from these events in the former Soviet Union to China, I of course understood in theoretical terms and statistics the contrast of all these developments in Russia surrounding the disintegration of the USSR compared to the success of China. But when I was involved in this process in Russia I had no contact with China – to my knowledge I never met anyone from Mainland China until 2002. I had just used Marxism and facts to understand the gigantic scale of what China had achieved.

In 2000 Putin became President of Russia, creating a new political situation which is beyond the scope of this article to analyse. At the same time Ken Livingstone, who had been elected Mayor of London, asked me to come back from Moscow to run London’s economic policy. As a result of this, I began to have practical contact with China. The Mayor of London had meetings with high level Chinese officials in which I participated. It was decided to establish London’s offices in China to promote relations with the country. In 2005, for the first time, I was able to visit China – the country from which I had learnt so much for so long! In 2008, after Ken Livingstone was no longer Mayor of London, I received an invitation – to begin teaching in Chinese universities. In 2013 I became a Senior Fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. There I could begin to interact with Chinese colleagues and enormously expand my knowledge of China’s economy. But it was a great deepening, it never contradicted the fundamental issues of Marxist analysis which had led me to pay so much attention to China decades before. But, of course, it had a great impact on me to see at first hand the rapid improvement in the life of China’s people compared to what I had seen in Russia. If in after the restoration of capitalism in Russia, and the destruction of the USSR, I saw everything going backward, in China I saw with my own eyes the life of the people going forward. I had understood this process from an intellectual point of view. But nevertheless, it is a different thing to see it at first hand.

Conclusion

I hope by giving an account of these personal experiences, in witnessing the consequences of the collapse of the USSR and their connection to the powerful social forces that created them, I might perhaps contribute some knowledge that is useful to China. Because the Chinese people have seen from the “inside”, from their own country, the success brought by the CPC but they cannot see it from the “outside”.

Naturally, as someone who is not Chinese, I cannot have the same personal experience as China. Instead, I first understood decades ago from fundamental Marxist analysis the brilliance of the achievements of the CPC. I will simply repeat what was said previously, because these facts are so fundamental in human history. In 1949 the CPC showed for the first time in human history how socialism could be created in a developing country. As a result of this in only just over 70 years, a single lifetime, China has shown how to take its country from almost the poorest in the world, due to foreign intervention, to becoming in only two to three years’ time a high-income country by international standards. That success from 1949 is itself the most extraordinary achievement in human history.

But from 1978 China also solved the problems which the CPSU failed to solve after World War II, with China creating the most rapid economic development in world history – with all the improvement of the lives of its people this created. In so doing the CPC ensured not only China’s national rejuvenation, but it saved world socialism from the danger which was created by the collapse of the USSR. Furthermore, seen from the viewpoint of Marxist theory this process is continuing – from their international impact particular attention should be paid to Xi Jinping’s concepts of the “common destiny of humanity” and of “common prosperity”.

But precisely because the Chinese people have lived through such a period of success, they have not seen the consequences of a disaster of the type I witnessed in the USSR. I sometimes become a little impatient with students who point to this or that problem in China which has not yet been overcome – because of course socialist construction will be a prolonged process in China. I think “if you had seen what I saw with the collapse of the USSR you would be more patient and understand better. You do not understand how lucky you are to be in China”. So perhaps giving some information on what it means to see the collapse of socialism and the disintegration of the USSR may be useful?

The lesson is transparently clear. China’s development depends on the CPC’s success. Any failure or departure from the CPC would lead to national disaster of the type I saw in the USSR. Regrettably, as I am not a Chinese citizen, I cannot participate in that process in the CPC. But I can understand it from outside.

The Chinese people can see from within their own country the development created by the CPC. But I could understand it, first, from the viewpoint of Marxism, a profound theoretical impact, and then from witnessing with my own eyes the contrast to this in the disaster in the disintegration of the USSR – a profound personal and emotional impact. Finally, something I had never imagined, I eventually could see with my own eyes China’s successful development, the improvement of the lives of its people, due to the CPC’s policies – the sharpest possible contrast compared to what I saw in Russia with the collapse of the USSR. These are very different ways of experiencing seeing the world – but they arrive at the same conclusion.

This article originally appeared in Chinese at guancha.cn.

[*] The most important for studying this is, of course, Marx and Deng Xiaoping and other Chinese leaders following Marx’s analysis. But among secondary sources particularly important was the recommendation to read Robert C Hsu’s Economic Theories in China, 1979–1988. This book misrepresents Marx but contains quite sufficient factual information, for those who have read Marx, to understand that China’s economic reform was guided by Marxism. Among secondary sources Hsu’s therefore remains one of the best sources for studying the economic discussions in China surrounding 1978 – provided it is understood that Hsu’s own analysis does not understand Marx!