China’s 8.1% GDP increase in 2021, following on from 2.2% in 2020, will exceed that of any other major economy. However, as is well known, China’s year-on-year growth rate fell to 4.9% in 2021’s third quarter and 4.0% in the 4th quarter, showing downward economic pressure.

Furthermore, China’s economy was aided in 2021 by an exceptionally strong trade performance. China’s annual imports rose in dollar terms by 30.1% in 2021 and exports rose by 29.9%. There were therefore signs of a slowing of very rapid growth of trade at the end of 2021 – although this was less sharp than for GDP. Taking a three-monthly average, to avoid distortions caused by a single month’s figures, annual growth of China’s exports fell from 30.7% in June to 23.3% in December, while the annual growth rate of imports fell from 37.1% to 19.5%. Whether such a strong trade performance as in 2021 can be repeated in 2022 clearly depends not only on conditions in China but on the state of the global economy.

Therefore, in addition to the assessment of China’s growth in 2021, it is necessary to look at both domestic and international facts to see economic perspectives.

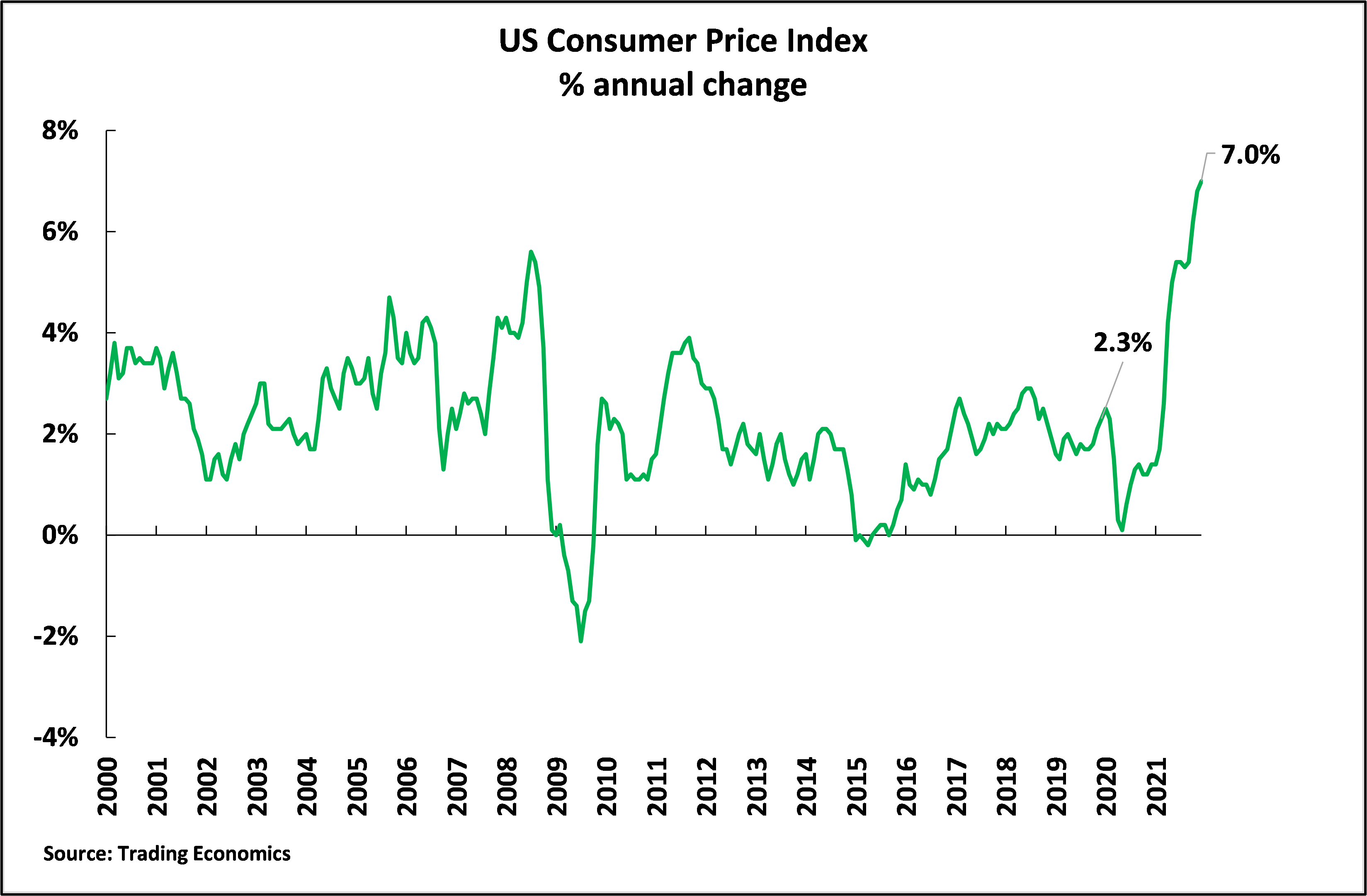

Starting with the international economy, there are strong reasons to conclude that global growth in 2022 will be weaker than in 2021. This is due both to general economic conditions and the strongly inflationary side effects of the type of stimulus packages which were launched by the Trump and Biden administrations – unless inflationary pressures are to become out of control U.S. this will force a significant tightening of U.S. monetary policy with consequent downward pressure on growth in the world’s largest economy. Similar pressures are likely in the European Union – the other major centre of the world economy in addition to the US and China. The effects of this U.S. inflationary pressure is therefore a significant risk for the world economy.

Looking at this danger in detail, in December U.S. consumer price inflation reached 7.0% – the highest rate for 40 years. Asset price inflation was even sharper – by October 2021, the latest data, U.S. house prices had increased by 19.1% year on year, which was even more rapid than the 14.1% before the sub-prime mortgage crisis. But such inflation was predictable given the nature of the stimulus packages launched by the Trump and Biden administration.

Taking fiscal policy, U.S. government spending rose by 9.7% of GDP in 2019-2020 – the largest increase in U.S. history apart from World War II. U.S. monetary policy was equally expansionary, the annual increase in M3 money supply reaching a peak of 27% – an increase almost twice as high as any other period in the last 60 years.

This enormous fiscal and monetary U.S. stimulus was almost entirely focussed on the consumer sector of the economy. Between the last quarter of 2019, the last before the pandemic, and the 3rd quarter of 2021, the latest available data, U.S. consumption increased by $1,571 billion. In comparison U.S. net fixed investment, that is taking into account depreciation, rose by $22 billion – or by only 1.4% of the increase in consumption! In short, an enormous increase in demand was pumped into the U.S. economy while almost nothing was contributed to the supply side. Under conditions where there was no great unused capacity in the U.S. economy a huge surge on the demand side of the economy, with no significant increase on the supply side, meant an inflationary surge was inevitable – and has duly taken place.

What led to such a serious error in economic policy? From a theoretical viewpoint it was the false conception that consumption is a contribution to economic growth. But this is simply false. Consumption, by definition, is not an input into production. So, the huge increase in consumption launched by the Trump/Biden stimulus packages did not aid the supply side of the U.S. economy.

From the political viewpoint the reason the Trump/Biden stimulus packages were entirely focussed on consumption was because the U.S. is a capitalist economy – that is, by definition, one in which the private sector has a dominant role in the means of production. This capitalist class, consequently, does not mind the state stimulating consumption, but it does not want it intervening in investment, that is in control of the means of production.

For this reason, the only time the U.S. has pursued an investment, a supply side, led stimulus policy was during World War II. – when the total priority of the U.S. was to defeat Japanese militarism and Nazi Germany. By 1944 79% of fixed investment in the U.S. was in the state sector. This achieved the greatest economic growth in U.S. economic history. Between 1940 and 1944 U.S. grew by 15% a year, the fastest short-term growth recorded by a major economy in world history. But this huge state intervention into the U.S. economy was against the interests of private capital – the share of wages, compared to profits, in the U.S. economy rose for three decades and inequality of income and wealth was sharply reduced. Consequently, except when facing mortal peril such as war, U.S. capital was determined that there would never again be a large-scale state led investment programme even if this resulted in slow U.S. economic growth.

Therefore, because of confused economic theory and political relations, Trump/Biden launched an almost entirely consumer focussed U.S. stimulus programme which inevitably produced the inflationary consequences already outlined. The inflationary consequences of this now require tightening of U.S. monetary policy which will slow its economy.

Given the U.S. economy’s size the resulting U.S. monetary policy tightening, generally expected to be launched by the Federal Reserve in March at the latest, will inevitably have consequences not confined to the U.S.. An increase in Federal Reserve interest rates will put upward pressure on interest rates in numerous countries. It is also likely to put upward pressure on the dollar’s exchange rate. This combination will have negative economic consequences for a number of countries.

It is to be hoped that the world will join hands to manage these financial risks, including via the IMF and G20, but nevertheless these risks will continue to exist, and sufficient multilateral action cannot be guaranteed.

This situation clearly has economic consequences for China. Economic growth for 2021 met projections. But there was significant downward pressure at the year’s end. Meanwhile China’s trade was somewhat slowing and there are negative trends in the world economy. It is therefore difficult to escape the conclusion that there must be a domestic stimulus during 2022 if the negative trends in the world economy are to be avoided. But it is also important to understand the unfavourable lessons of the Trump/Biden stimulus packages and therefore to note that a stimulus in China only on the demand side of the economy, that is on consumption, will have negative consequences. Instead, stimulus will have to significantly include the economy’s supply side – that is investment.

In summary, China in 2022 will face more negative global economic trends than in 2021. This will clearly require more domestic stimulus in China while making it necessary to avoid the errors of Trump/Biden administrations.

This article was originally published in Global Times in English and Chinese.