President Xi Jinping’s introduction of the term “Common Prosperity” has led to an important discussion both inside and outside China. The aim of Common Prosperity is, of course, not at all limited to purely economic objectives. Its goals are far wider, including to ensure the rise in the living standards of the Chinese people, to increase social cohesion and political stability, and thereby to play an overall fundamental role in China’s national rejuvenation.

The response within China to Common Prosperity has been a very wide welcome. But it would be reasonable to say that a major part of this discussion has focussed on Common Prosperity’s social and political consequences. However, it is also important to understand that Common Prosperity is correct from an economic point of view. Indeed, Common Prosperity is a strikingly powerful and original way to analyse the interrelation of economic, social and political questions in the period of China’s advance after 1978 – and more generally issues of socialist development. Attempting to analyse some of these issues is a chief goal of this article.

To examine these questions, as always, the method of “seek truth from facts” needs to be followed. This is particularly important as the arguments of those in the U.S. who have criticised Common Prosperity, such as George Soros, and those who echo them in China, are refuted not only by China but even by the factual development of the U.S. itself. Furthermore, their arguments are not simply refuted by the facts but are contradicted by economic theory – as explained most succinctly by Marx but as can also be clearly followed in terms of “Western economics”.

The interrelation of economic facts and economic theory

Examining the specifically economic basis of Common Prosperity is important for several reasons. First, because an attempt has been made outside China, by figures such as George Soros, to claim that Common Prosperity is economically damaging and that instead China should not take any action against social inequality. This forms an ideological part of the new U.S. cold war against China. Such criticisms have also been echoed by a few commentators in China. Second, because while the goal of Common Prosperity is not only economic nevertheless, of course, it must be economically logical – a policy which damaged the economy could not be sustained over a long period. Third, a more minor matter, but of some economic significance, claims that Common Prosperity is economically damaging are used outside China to attempt to discourage inward foreign direct investment into China. As will be seen such attempts are not successful but nevertheless it is useful to refute them.

This article, therefore, aims to analyse a number of interrelated issues.

- The connection of Common Prosperity to basic questions of long-term economic development.

- The way that the change in the People’s Republic of China’s economic structure in 1978 necessarily posed the question of inequality in a different way to that prior to 1978 and the way that Common Prosperity deals with the issues this raises.

- More immediate questions of the policy of Common Prosperity and the factual and theoretical errors in arguments against it – as considered in particular using a comparison to the US.

- The reasons why Soros and some others in the U.S. have used erroneous arguments against Common Prosperity to attempt to persuade foreign companies not to invest in China – and why, because these arguments are false, such attempts have been shown to be unsuccessful.

Section 1 – Common Prosperity and Socialist Economic Development

Who has attacked Common Prosperity?

The strongest attempted criticisms of the policy of Common Prosperity have come from the U.S.. In particular they were led by billionaire George Soros in a widely publicised article in the Wall Street Journal which attacked the decision of the U.S. company Blackrock, the world’s largest asset manager, to launch an investment fund in China. Soros specifically attempted to argue that the Common Prosperity policy would be economically damaging to foreign investors in China: “The president [Xi Jinping] recently launched his “Common Prosperity” program… It seeks to reduce inequality by distributing the wealth of the rich to the general population. That does not augur well for foreign investors.” Soros declared: “Pouring billions of dollars into China now is a tragic mistake. It is likely to lose money for BlackRock’s clients and, more important, will damage the national security interests of the U.S. and other democracies.”

For those tempted to take Soros’s arguments seriously it may first be noted that he has a track record of disastrously inaccurate judgements created by confusing his right-wing politics with economic realities in regard to Communist and former Communist countries. For example, in Russia Soros was persuaded by pro-Western forces to participate in the proposed privatisation of telecommunications company Svyazinvest. The present author knows this situation directly as he was hired by a potential rival bidder to evaluate this proposed privatisation – my report was that purely economic/business examination showed that this would be a terrible investment. Soros, however, confusing politics and economics, went ahead and participated in a bid involving pro-U.S. forces. The result was a huge loss of hundreds of millions of dollars in what Soros later called the worst investment decision he ever made.

Attacks on Common Prosperity from the U.S. have also been echoed by a small number of figures within China such as Zhang Weiying. Zhang Weiying argued that loosing faith in market forces, and if there is strong government intervention, this will lead to common poverty. And that the best way to increase the income of the middle class is to further free up entrepreneurs and market competition.

As will be seen the attacks of Soros and Zhang Weiying on Common Prosperity are contradicted by both the facts of economic development and economic theory – the two being inseparably interconnected.

Socialist market economy

To understand most clearly the correctness of the policy of Common Prosperity from an economic viewpoint, and simultaneously its striking originality and its continuity with Marxist theory, it is most useful to go back to the most fundamental issues of China’s “socialist market economy”. As noted these can be seen most lucidly from the point of view of Marx’s economics but, in a slightly longer and less clear form, they can also be easily understood in terms of “Western economics”. This then allows Common Prosperity to be seen not only from the point of view of its benefit to society but from a fundamental theoretical economic viewpoint.

To start with the fundamentals of long-term development, Marx set out clearly that the transition from capitalism to fully developed socialism would take a prolonged historical period. More precisely in the Communist Manifesto he noted: “The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degree, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralise all instruments of production in the hands of the State, i.e., of the proletariat organised as the ruling class; and to increase the total productive forces as rapidly as possible.” Note Marx’s use of the term “by degree.” Marx, therefore, clearly envisaged a period during which political power would be socialist, held by the working class, but in the economy both state-owned property and private property would exist. This is clearly the political and economic structure of China today.

Such a structure has a clear implication for incomes and for inequality. As not only state property but also capitalist property will exist therefore so also will income from capitalist property. Thus, a necessary corollary of this analysis of Marx is that in a period after socialist state power has been established then, as well as a state sector, capitalist property income will still exist. This directly leads to issues of inequality which are related to the questions dealt with by Common Prosperity. The interrelation of Marx’s analysis with the development of socialist society, and the consequences of the point in time at which a transition to socialism takes place, will then become clear from issues analysed below.

Payment according to work

Turning from property income to income from labour, which is of course the basis of the living standard of the overwhelming majority of China’s population, the system of payment outlined by Marx for the primary period of socialist construction is well known. Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Program, one of his last works, and therefore embodying his most mature thought, analyses that after the initial transition from capitalism to socialism: “What we are dealing with here is a communist society, not as it has developed on its own foundations, but on the contrary, just as it emerges from capitalist society.” Marx then set out his famous formula of the goal of the transition to a communist society, the principle of the latter of which was: “from each according to their ability to each according to their needs.”

But Marx outlined that in the first period of socialism this goal would not be possible. Payment would have to be based on work, not simple distribution according to need. As he put it. “Accordingly, the individual producer receives back from society – after the deductions have been made – exactly what he gives to it….

“Here obviously the same principle prevails as that which regulates the exchange of commodities, as far as this is exchange of equal values…. the same principle prevails as in the exchange of commodity equivalents: a given amount of labour in one form is exchanged for an equal amount of labour in another form.

Note here that Marx writes of the “exchange of equal values.” This therefore applied in the initial stage of a socialist society as far as the distribution amongst the individual producers was concerned. Marx noted that only after a prolonged transition would payment according to work be replaced with the ultimately desired goal, distribution of products according to members of society’s needs. This again, as will be seen, is in turn directly related to the issues analysed in Common Prosperity.

Marx noted: “Right can never be higher than the economic structure of society and its cultural development which this determines. In a higher phase of communist society… after the productive forces have also increased… and all the springs of common wealth flow more abundantly – only then can the narrow horizon of bourgeois right be crossed in its entirety and society inscribe on its banners: From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs!”

The feature which flows from this situation during the primary stage of socialism, that of “payment according to work”, as is well known is the guiding principle of China – regrettably payment according to need will only be possible at a much higher stage of development of socialism. However, it should be noted that this principle of payment according to work does not itself specifically deal with the relation of such income to the quite different source of payments from capitalist property income – which, as already been noted, will also exist during the primary stage of socialism. As will be seen this issue overlaps with questions dealt with in Common Prosperity

Historical development is based on the increasing division/socialisation of labour

The economic and social consequences of the issues involved in these questions become still clearer if it is noted that the analyses by Marx on the political and economic aspects of the transition to socialism flowed inevitably from his fundamental analysis of the development of human society in the theory of historical materialism. The foundation of this, as set out consistently from Marx’s first formulation in The German Ideology, was that the history of the development of human society was based on increasing division/socialisation of labour. As he noted: “How far the productive forces of a nation are developed is shown most manifestly by the degree to which the division of labour has been carried. Each new productive force . . . causes a further development of the division of labour.”[1]

The transition from capitalism to socialism was therefore itself based on the highest degree of development, so far, of division/socialisation of labour. As Marx put it in Capital on the transition to socialism: “Centralisation of the means of production and socialisation of labour at last reach a point where they become incompatible with their capitalist integument. This integument is burst asunder. The knell of capitalist private property sounds. The expropriators are expropriated.”[2]

The limits on the socialisation of labour before the transition to socialism

Within the above fundamental framework it is important to note that in analysing this increasing socialisation of labour Marx was, of course, outlining the overall historical development of capitalist society and of its most advanced productive forces. He did not at all envisage theoretically that the transition to socialism would only occur after all production was comprehensively socialised. Nor did this occur practically in countries in which the transition to socialism took place – Russia, China, Vietnam, Cuba etc. In these countries, when they embarked on a socialist path, while the most advanced economic sectors were based on socialised production large parts of urban production, and almost all of agriculture, was not based on highly socialised production. That is, a part of the economy was based on highly socialised production, and another part was based on medium and small scale production. The transition to socialism would, therefore, necessarily occur before all sectors of the economy became dominated by large scale socialised production.

As Stalin put it regarding the practical political policy issues which flowed from this situation: “so, what is to be done if not all, but only part of the means of production have been socialized, yet the conditions are favourable for the assumption of power by the proletariat – should the proletariat assume power and should commodity production be abolished immediately thereafter?

“We cannot, of course, regard as an answer the opinion of certain half-baked Marxists who believe that under such conditions the thing to do is to refrain from taking power and to wait until capitalism has succeeded in ruining the millions of small and medium producers and converting them into farm labourers and in concentrating the means of production in agriculture, and that only after this would it be possible to consider the assumption of power by the proletariat and the socialization of all the means of production. Naturally, this is a ‘solution’ which Marxists cannot accept…

“Nor can we regard as an answer the opinion of other half-baked Marxists, who think that the thing to do would be to assume power and to expropriate the small and medium rural producers and to socialize their means of production. Marxists cannot adopt this senseless and criminal course either, because it would destroy all chances of victory for the proletarian revolution, and would throw the peasantry into the camp of the enemies of the proletariat for a long time.”[3]

That is, both from the point of view of Marxist theory, and from the factual point of view, the working class would take state power when the most advanced sectors of the economy were constituted by socialised production but many other sectors of the urban economy, and almost all the rural economy, was not based on highly socialised production. What policy should therefore be pursued in this situation? It will be seen that this determines fundamental issues involved in Common Prosperity and which illustrates its integration of economic, social and political aspects of the situation.

Summary

To briefly summarise these fundamental economic points, in order to make clear their connection to the policy of Common Prosperity, the analysis which Marx gave of this first period of socialism was therefore that:

- “The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degree, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralise all instruments of production in the hands of the State, i.e., of the proletariat organised as the ruling class; and to increase the total productive forces as rapidly as possible.” By degree” means there would be a prolonged period during which both state and non-state forms of property would exist in the economy – within the framework of socialist political state power.

- Because in addition to state property capitalist property would also exist during this initial period of socialism so also would income from capitalist property.

- The transition to socialism would take place when some parts of the economy were based on highly socialised production, but other parts of the economy were dominated by relatively unsocialised production.

- In this initial period payment for labour could only be by work and not according to need.

These features, of course, constitute the basis of China’s analysis that it is in the “primary stage of socialism”, as adopted by China after Reform and Opening Up in 1978 – and show that this is fully in line with Marx’s analysis. These fundamental economic issues then define the framework within which socialist development takes place, and directly link to issues dealt with by Common Prosperity.

Section 2 – The Different Way Inequality was Posed in China Fefore and After 1978

The relation of China’s economic structure from 1949-78 and the Soviet system

Within the framework of the fundamental points on the overall course of socialist development analysed above, an issue is necessarily posed on the relation of inequality to the economic structure of the People’s Republic of China – both as it existed prior to 1978 and as it existed after that date. As will be seen this directly overlaps with the question of the unprecedented economic growth of socialist China after 1978, contrasted to the final economic failure, leading to eventual collapse, of the USSR’s socialist system. It will rapidly become clear that the different economic structures involved in these questions directly relate to problems of social inequality and the issues addressed by Common Prosperity. Factually analysing this makes clear that the strength and originality of the concept of Common Prosperity allows the overcoming of previously false answers given to questions of the relation between economic growth on the one hand and inequality and social development on the other.

Analysing first the pre-1978 period, It is well known that while China’s economic system from 1949 to 1978 was not at all a mechanical copy of the Soviet system after 1929 nevertheless it shared certain fundamental characteristics with it. In particular, in contrast to the post-1978 socialist market economy, China’s pre-1978 economic system had finally culminated in the state ownership of not only the most large scale/socialised sectors of production but of extremely wide sectors of the urban economy. Similarly in agriculture not a household responsibility system, that is individualised production, but communes, that is collectivised agriculture existed. This was in parallel with the post-1929 system in the USSR in which almost all of the urban economy was taken into the state sector and agriculture was collectivised. That is, in the post-1929 Soviet system, the statification of the economy was not carried out “by degree”, as envisaged by Marx, but in a single step.

The specific geopolitical argument put forward to justify this post-1929 Soviet system is that it was necessary for military reasons. The USSR was faced with the threat of military attack by capitalist powers – which indeed occurred in 1941 by Nazi Germany. Therefore, it is argued, everything else had to be subordinated to the necessity to create military heavy industry as rapidly as possible and the only way to achieve this was via statification of the economy as rapidly as possible – to ensure an overwhelming priority for resources to be poured into military industry.

This is indeed, a very serious argument – in the famous dictum of Lenin, politics must take precedence over economics. And the rapid development of military industry in the USSR after 1929 did indeed lead to rapid economic growth, centred in military heavy industry, and to Soviet victory in World War II.

But this geopolitical argument does not alter the fact that the Soviet economic system after 1929 clearly differed from that envisaged by Marx – to be precise, the rapid 100% statification of the entire Soviet economy after 1929, in economic terms, was an “ultra-left” deviation from Marx, that is it constituted an attempt to jump over an historical period. Instead of wresting capital from the bourgeoisie “by degree”, as Marx had argued for, essentially all capital was taken from the bourgeoisie in a single step. Given this it is then necessary to analyse the economic consequences of the different economic structure of the post-1929 USSR, and the economy of the People’s Republic of China from 1949-1978, compared to the post-1978 structure of China’s economy. This, as will be seen, directly leads to the economic and social issues of Common Prosperity.

The economic policy of the USSR after World War II

Given the historical framework already outlined, after the successful defeat of the German fascist attack on the USSR the issue was therefore then posed of what economic system the USSR should follow? The decision was made to continue the essentially 100% statified model adopted in 1929 – rather than moving closer to the system envisaged by Marx as was followed by China after 1978. This had a further necessary economic implication for the USSR. The decision was made to develop a relatively “self-enclosed” Soviet economy – rather than attempting to insert the Soviet economy into world trade. This policy was also contrary to Marx’s analysis of the increasing socialisation of production – globalisation is precisely one of the highest developments of socialised production. It is clear from the factual long term post-World War II economic results that this combination of policies was an extremely serious mistake by the USSR. It also shows the correctness of the economic path embarked on by China in 1978 and why this course must not be abandoned. This then leads directly to the issues involved in Common Prosperity

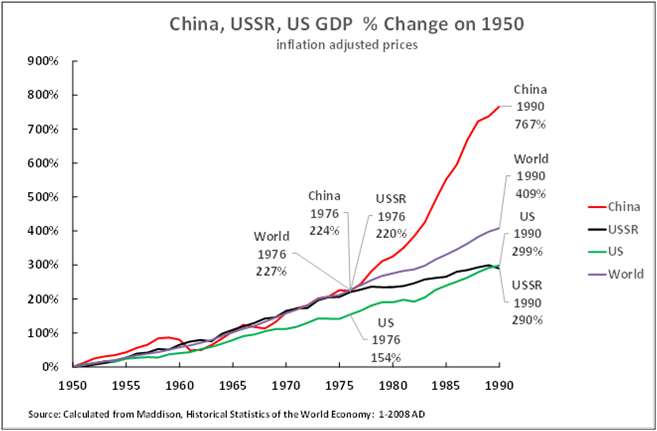

To illustrate the economic results involved in these processes Figure 1 shows Soviet economic growth from 1950, which may be taken as the end of the post-World War II reconstruction period, to 1976, the year of the death of Mao Zedong. During this period total Soviet economic growth was 220% – faster than the U.S.’s 154% but not above the world average of 227%. It may be seen that in the same period China’s economic growth was essentially the same as the USSR – with a 224% expansion. The social achievements in China in 1949-78, registered in increase in life expectancy, were a literal “miracle”, the greatest in any country in human history, but the economic record was not its equal – the foundations of an industrialised economy were laid but the overall economic growth rate was not exceptional by international standards.The slowing of the Soviet economy

Figure 1

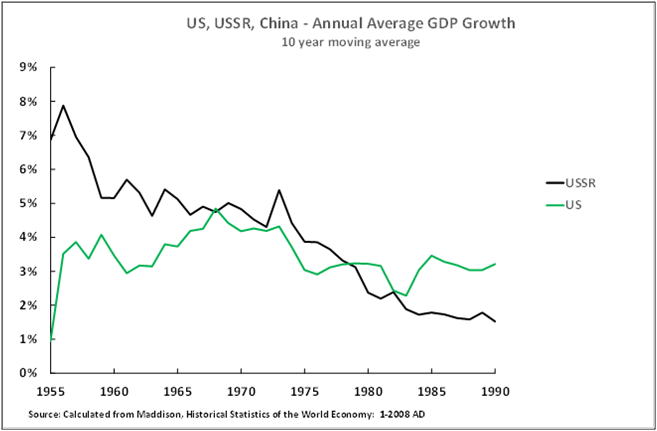

The post-World War II Soviet economy then continued to slow further until by the late 1970s its economic growth was even lower than the U.S. – see Figure 2. In summary the continuation of the 100% statified and self-enclosed model of the post-1929 USSR culminated in a severe international economic defeat. It was this economic failure which, in the last analysis, determined the failure and collapse of the USSR.

Figure 2

To summarise the 100% statified and self-contained Soviet economy, which had been successful in the short term (12 year) period of essentially military dominated struggle against Nazi Germany proved inadequate for the decades long post-World War II economic struggle against the U.S.. As the leader of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, Genady Zyuganov, noted in 2008 regarding China’s alternative policy of Reform and Opening Up: “Had we learned from the success of China earlier, the Soviet Union would not have dissolved.”

The contrast of the USSR to China’s success with reform and opening up after 1978 is clear from Figure 1 above. After 1978, when it ceased to follow the 100% statified and relatively self-enclosed Soviet model, and moved to one more in line with Marx, China’s rate of economic growth far overtook both the U.S and the world average. By 1990, the last year of the USSR, China’s GDP had grown by 767% from 1950 – compared to 299% for the US, 290% for the USSR, and 409% for the world average. In short, after 1978 adopting an economic structure in line with Marx, China produced the fastest sustained economic growth in any major country in world history. It was this new economic policy and structure after 1978 which allowed China not only to avoid the economic failure of the USSR by the 1970s but to grow far more rapidly than any major capitalist economy.

These facts have a clear implication. Maintenance of the socialist market economy system is therefore vital for China’s development and national rejuvenation. Any overturn of this system, and a return to the pre-1978 economic structures, let alone those of the USSR, would block China’s economic development. However, as will be seen, this socialist market economy economic system also created issues of inequality which Common Prosperity fundamentally deals with.

Lessons for the world

Before proceeding to deal with the specific issues of inequality addressed by Common Prosperity it is, therefore, crucial both inside and outside China to understand these enormous facts of world economic development – which have largely determined world history in the last 50 years. Because China’s economic success is now so clear there are now attempts being made in a few circles in the West to deny the key change in China’s economic policy made in 1978. This is not correct. As can be seen while there is a continuity in China’s political structures since 1949, with the creation of a socialist state and the leading role of the Communist Party of China (CPC), there was a key change in China’s economic policy after 1978. There was a break from the economic model maintained in the USSR after 1929, and a shift to closer to the economic system envisaged by Marx. Indeed it is clear that the key economic concepts put forward by Deng Xiaoping and Chen Yun after 1978 moved China to an economic system more in line with Marx – in fact, their analyses are in many cases paraphrases of Marx. These policies produced the greatest economic growth in the history of the world – showing that what was one of the greatest revolutions in world economic history, the creation of an previously unprecedented economic structure in China’s socialist market economy, was simultaneously an “innovation” in economic practice and a “return to Marx” in economic theory.

As Xi Jinping put it regarding these two periods of China’s post-1949 development: “The two phases – at once related to and distinct from each other – are both pragmatic explorations in building socialism conducted by the people under the leadership of the Party. Chinese socialism was initiated after the launch of reform and opening up and based on more than 20 years of development since the socialist system was established in the 1950s after the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was founded. Although the two historical phases are very different in their guiding thoughts, principles, policies, and practical work, they are by no means separated from or opposed to each other. We should neither negate the pre- reform-and-opening-up phase in comparison with the post-reform-and -opening-up phase, nor the converse.[4]

To summarise, it may therefore be seen that after 1949 in China there was:

- Continuity in political power and leadership by the CPC in China from 1949 to the present day,

- A fundamental change in economic policy, creating new social questions, which will be analysed below, from 1978 onwards.

But, for reasons that will now be examined, this new economic policy after 1978 also led to social issues which the concept of Common Prosperity precisely deals with.

Section 3 – Common Prosperity and Social Inequality Under Socialism and Capitalism

Inequality

We will now turn from macroeconomic processes to examine their social and political consequences – in particular as they relate to social inequality. To do so it is again clarificatory to look at economic fundamentals – specifically how the consumption of different classes is financed and its relation to investment and economic growth. This can most clearly be seen in Marx but, once again, it can also be analysed in terms of “Western economics”. These issues lead directly to the questions analysed by Common Prosperity.

Marx noted that different classes in society had different sources of income. The working class receives its income from wages. The petit bourgeoisie, of which by far the largest part is the peasantry, receives its income from sales of products of its own labour. These two classes form the overwhelming majority of the population of every country, and will therefore be referred to here as the ordinary population. Both these classes therefore, in different ways, earn their income from labour – the working class by selling its labour power in return for a wage, the petit-bourgeoisie by selling the products of its labour. Both therefore, in different social forms, correspond to the category of “payment according to work”. The capitalist class, in contrast receives its income from property. In strict Marxist terms, the capitalist class receives its income from surplus value created by the working class but, for present purposes, understanding that the capitalist class receives its income from property will suffice for analysis.

Relative lack of Inequality under the Soviet model

The different economic structures already analysed have inevitable consequences for social inequality. In particular the essentially 100% statification of the economy in the post-1929 Soviet model, and during much of the period of the pre-1978 model in the People’s Republic of China, after the initial period of transition to the socialist system after 1949, necessarily meant that income from capitalist property was not a major issue. Inequality of income could and did exist, but in all societies, including capitalist societies, inequality in income is much less than inequality in wealth. Therefore an essentially 100% statified economy is necessarily relatively egalitarian compared to one in which capitalist property exists.

The result of this situation was that the post-1929 Soviet economic model did not correspond to the analysis of Marx, and was relatively inefficient for long term development, but its economic structure made it relatively egalitarian. There were similar pressures in pre-1978 China. This created the erroneous concept in some ultra-left circles in China and elsewhere that socialism was the equal sharing out of a relatively low standard of living – a concept which, needless to say, is not Marx’s and was rightly strongly attacked by Deng Xiaoping. For Marx, each new mode of production would lead to a more rapid development of the productive forces than the one before – so socialism would lead to more rapid economic growth and a higher standard of living than capitalism, not to slower growth, a lower standard of living, but more egalitarianism.

China’s post-1978 economic reform in contrast, and as already analysed, therefore created an economic structure which was more in line with that outlined by Marx, generating the most rapid sustained growth in world history. The structure was precisely the socialist political power of the working class combined with an economic structure in which both a leading state economic sector and a non-state sector would exist. This post-1978 policy therefore necessarily, and correctly, meant correction of the ultra-left error of total elimination of a capitalist class within this socialist political structure. But this also led to issues addressed by Common Prosperity.

Capitalist property income

With the recreation of a substantial capitalist class after 1978, however, necessarily the issue of income from property simultaneously ceased to be an insignificant question. On the contrary, as capitalist property income became a serious issue therefore equally so did the question of what would this capitalist property income be used for? As this question overlaps with the attacks made on Common Prosperity by some figures in the United States, notably Soros, it is worth considering the two issues together. The questions involved become particularly clear if both the factual and theoretical errors of Soros and similar critics of Common Prosperity are considered and a comparison is made to the U.S. itself.

Starting with the facts, Soros and similar analyses argue that greater equality is bad for economic development and efficiency – therefore that inequality is beneficial for the economy. But the factual evidence, even from the certainly capitalist U.S., clearly refutes this.

In the last decades U.S. inequality in both income and wealth has risen sharply. In 1974 the bottom 50% of U.S. earners received 19.8% of all incomes, by 2019 this had fallen to 13.3%. In the same period the share of U.S. total incomes received by the top 1% rose from 10.4% to 18.8%. In wealth, again in the same period, the share of the bottom 50% fell from 2.1% to 1.5%, while the share of the top 1% rose from 23.7% to 34.9%.

But in terms of economic growth in the same period, taking a 10-year moving average to remove the effect of short-term business cycle fluctuations, annual average U.S. GDP growth fell from 3.1% to 1.7%. The period of greater inequality was therefore associated with lower economic growth and the period of greater equality with faster economic growth – the exact opposite of Soros’s claim.

The different uses of income from property

These facts of the U.S. economy are easily explained theoretically, and the same issues also show why the policy of Common Prosperity will be beneficial. Once again Marx, in most detail in the Second Volume of Capital, gave the most succinct theoretical explanation of this, but the data can also clearly be followed in terms of “Western economics”.

Marx pointed out that consumption could be divided into two parts from the point of view of the sources of income used to purchase it. The first was necessary consumption, which sustained the living standard of the mass of the population – in technical terms, that is, it allowed the working class to reproduce itself, that is to not only feed itself, but to raise children etc. The ability to purchase this consumption came from the wages and other incomes of the ordinary population. This necessary income and consumption was historically determined – that is it rose as society became more prosperous. It might be roughly thought of as equivalent to an average or ordinary income in any historical period. But its defining feature was that this consumption was financed by the work of the working class and the personal work of peasants, the urban self-employed etc. In contrast, the capitalist class, by definition, receives its income not from wages, or its personal work, but from income from property – in a modern economy overwhelmingly from company profits.

Such capitalist property income, however, can then be used in two different ways.

- It can be invested in production or,

- It can be used, in Marx’s words, for purchase of: “Articles of luxury, which enter into the consumption of only the capitalist class.”[5] (It is important to note that in technical economic terms “luxury consumption” is not simply “luxurious goods” (sports cars, fur coats etc) but any form of property income which is consumed instead of being invested into production. Secondary features noted under Common Prosperity, for example conspicuous consumption, excessive “celebrity culture” etc derive from this economic foundation of luxury consumption)

These two different uses of property income, however, have completely different economic effects. Investment is an input into production and therefore generates economic growth – every economic system requires investment. But luxury consumption is not an input into production, and therefore is not an input into economic growth. Any part of property income which is used for luxury consumption, instead of for investment, consequently reduces inputs into economic growth.

Therefore, put in fundamental economic terms, insofar as the capitalist class uses its property income for investment it is carrying out, in a capitalist form, an investment function – and investment is necessary in any society. But insofar as the capitalist class engages in luxury consumption it is not creating an input into production, but is instead using up resources which could either be used for increasing the proportion of the economy available for consumption by the mass of the population or which could be used for increasing investment and therefore generating economic growth. Any economic system, therefore, will benefit from the use of property income for investment and suffers adverse consequences from the use of property income for luxury consumption.

Under a fully developed socialist economy the luxury consumption of the capitalist class would be zero, but China is in the primary stage of socialism – a fully developed socialist system is in the future. In this primary stage of socialism, a capitalist class will exist – although it will not hold state power. As long as a capitalist class exists, in addition to it carrying out desirable investment it will also carry out some luxury consumption. Until the advanced stage of socialism is achieved, after a long period of socialist construction, the goal therefore cannot be total elimination of luxury consumption financed from property income but the goal must be its minimisation in order to limit its negative economic and social consequences.This provides a fundamental economic base of Common Prosperity.

Luxury consumption in capitalism

It should be noted that this economic principle is implicitly understood even within capitalist societies. As is well known the population of the Scandinavian countries – Sweden, Norway, Finland and Denmark – have among the highest levels of satisfaction of the population with the quality of life in the capitalist world. Compared with a theoretical maximum of 100%, satisfaction with life in Denmark was 82%, Finland 81%, and Sweden 79%. All the Scandinavian countries have higher levels of life satisfaction than in the unregulated economies of U.S. or U.K. for example.

But the “Scandinavian” capitalist model precisely rests on the distinction between the use of capitalist property income for investment versus that for luxury consumption. The classic “Scandinavian” capitalist model aims at minimising luxury consumption, and with it inequality in consumption, while permitting the capitalist class to carry out high levels of investment. That is, within this Scandinavian model, use of property income for investment is considered good and luxury consumption is considered bad. This means that there is the maximum pressure on capitalist property income to either be redistributed for the general consumption of the population (via taxation etc.) or to be invested for economic development. Therefore, the Scandinavian capitalist model precisely follows the theoretical distinction made by Marx – although of course within a capitalist framework and not a socialist one.

Why increasing inequality in the U.S. was associated with economic slowing

This framework also immediately makes clear why the increasing inequality in the U.S, contrary to the analysis of Soros and others, was associated not with faster economic growth but with economic slowing. Capitalist property income in the U.S. has risen as a percentage of the economy – the net operating surplus of private companies rose from 21.0% of GDP in 1974 to 24.6% in 2020. However, this rising property income was not invested – the share of private fixed investment in U.S. GDP fell from 21.8% to 17.8% in the same period. That is, in technical economic terms, the percentage of property income used for investment fell while that used for luxury consumption rose. Within the U.S. capitalist model, in which the private and not the state sector of the economy is dominant, there is no mechanism to compel capitalist property income to be used for productive investment. Instead, increased capitalist property income may be used for luxury consumption.

In the specific case of the U.S. factual examination shows that the fundamental mechanism of this shift in U.S. capitalist property income into luxury consumption, rather than investment, was rising dividend payments by U.S. companies – however other mechanisms of diversion of capitalist property income into luxury consumption rather than investment other than by dividend payments can be envisaged. Payment of dividends by U.S. companies increased from 1.9% of GDP in 1974 to 5.2% of GDP in 2020. In terms of abstract economic theory such dividend payments from an individual company could have been used for productive investment in other companies, but the fact that the overall share of private fixed investment in GDP fell shows factually that this did not occur. That is, in a technical economic sense, it is clear the dividends distributed to U.S. shareholders were not used for investment but, in the technical economic sense, for luxury consumption. Therefore, precisely as would be predicted from economic theory, the rising share of property income in U.S. GDP, and increasing inequality, led to a slowdown in economic growth not to an increase.

As this period of U.S. economic slowdown was associated with the “deregulation” policies followed from Reagan onwards, the argument that the way to deal with increasing inequality is by free market methods is also simply shown to be factually false. Free market methods and deregulation were associated with both increasing inequality and economic slowdown in the U.S..

The relation of these issues to China’s policy of Common Prosperity is clear. Luxury consumption, because it is not an input into production, is an economically wasteful use of property income. Redistribution of such income can be used either (or both) to increase resources available for the living standard of the bulk of the population, which will be socially beneficial, or it can be invested – in which case it will increase economic growth, which will also raise living standards.

Section 4 – Common Prosperity and the Failure of Soros’s Attack on China

Foreign investment into China

Finally, these issues also overlap with the issue of foreign investment into China – and therefore why Soros and others are making a determined campaign to try to dissuade foreign companies from investing in China. The practical actions by foreign companies, however, against Soros advice, gives a particularly clear example of the maxim “actions speak louder than words”. The “action” is that foreign investment is flowing into China at record levels. The “words” are that U.S. political media, and a few economic figures, led by Soros, have been unsuccessfully campaigning to try to stop foreign investment into China.

Therefore, although it is not the primary goal of Common Prosperity, its strengthening of China’s social cohesion and economic development will also make China an attractive destination for foreign investment – which is contrary to the U.S.’s cold war strategy. It is precisely because China has become a more attractive destination for foreign investment that Soros has therefore been active in the Wall Street Journal, and also the Financial Times, trying to lessen this.

But, as shown above, economic analysis shows that Common Prosperity, and reduction of the proportion of the economy used for luxury consumption, will not damage China’s economy but will strengthen it. It is because Soros is wrong from the fundamental economic viewpoint that his claims are refuted both by the facts of the U.S. economy and the actions of foreign investors in China.

The global macroeconomic situation

To understand the present context of this situation of foreign investment into China in more detail it is evident that the immediate global macroeconomic background to current events, and international discussion of Common Prosperity, is China’s success in controlling the COVID pandemic – in particular compared to the U.S.. This in turn has produced a sharp shift in the international relation of economic forces in China’s favour.

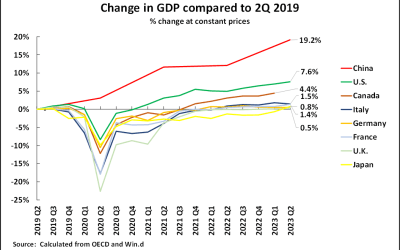

Taking a two-year period, to avoid short-term distortions of data in both China and the U.S. during the onslaught of the pandemic in 2020, then from the 2nd quarter of 2019 to the 2nd quarter of 2021, China’s economy grew by 11.4% and the U.S. by 2.0%. In real terms, there was a 9.4% increase in the size of China’s GDP compared to the U.S.. Taking the next five years, the IMF projects China’s economy will grow by 68.2% compared to the US’s 29.0% – i.e. China’s economy will grow well over twice as fast as the U.S.

Given the much more rapid recovery of China from COVID than the U.S., China has become a magnet attracting foreign investment – as has been noted even within the U.S. As Nicholas Lardy, of the Peterson Institute, regarded as one of the top U.S. experts on China’s economy, concluded in July: “Global economic decoupling from China… is not happening… China continues to attract record amounts both of foreign direct investment and inflows of portfolio investment…

“As China continues to lead the global recovery from the adverse economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic… foreign multinationals are doubling down on their investments in China… Last year, as global foreign direct investment flows slumped by almost two-fifths, China’s inbound direct investment expanded by more than 10 percent to reach $212 billion. As a result, China’s share of global foreign direct investment in 2020 reached an all-time high of one quarter, almost twice its share in 2019.

“Foreign direct investment inflows continue to accelerate in 2021, reaching $98 billion in the first quarter, almost three times the inflows in the first quarter of 2020. Thus, China’s total direct investment inflows this year will almost certainly reach a new all-time high…

“Portfolio inflows into China are also surging. Equity investors have purchased about $35 billion in Chinese onshore stocks so far this year, a pace 50 percent higher than in 2019. Foreign purchases of Chinese government bonds are even larger at $75 billion so far this year, but also running 50 percent higher than in 2019.”

Taking the most data for 2021, up to July, foreign investment into China increased by 36% compared to the preceding year.

U.S. companies prepare to step up investment in China

Given this global situation U.S. companies were naturally among those gearing up to increase investment in China. As Bloomberg News headlined in September 2020: “Wall Street Struggles to Keep Up in China Mutual Fund Boom”. This noted: “More than 40 global companies have set up joint-ventures… BlackRock last month received approval to set up a fully controlled mutual fund company. Vanguard has a… joint venture with Ant Group, and said it’s in the process of applying for a mutual-fund license. UBS Group AG said it is weighing options to expand.”

This year therefore saw the largest US companies stepping up investment in China. Blackrock, the world’s largest asset manager, announced a new $1 billion fund for investment in China. Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater, the world’s largest hedge fund, has similarly been urging investment in China. This surge of foreign investment into China is clearly contradictory to current attempts by U.S. administrations to launch a “new cold war” against China. This explains why an attack on this investment flow was launched by George Soros using the factually and theoretically false arguments which have already been analysed.

However, precisely for the reasons outlined, Common Prosperity is not damaging to China’s economy but will aid it. This is why Soros’s attempt to dissuade foreign companies from investing in China has failed. Soros is simply making political propaganda not any coherent economic argument. Companies basing themselves on propaganda, and not economic realities, will of course suffer major losses – just as Soros did in his previous disastrous intervention around Russia’s Svyazinvest.

The beneficial economic effects of Common Prosperity

The fundamental issues analysed above make the correctness of Common Prosperity clear and simultaneously explain its originality. As has been seen the issues of economic structure and inequality are inextricably related and also lead to two false solutions which Common Prosperity successfully refutes and provides the coherent alternative to.

Common Prosperity, in contrast, corresponds to both socially and politically desirable goals and in fundamental terms is the rational use of the economic structure of China. Within a socialist political system, and the leading role of the state sector, during the current primary stage of socialism, a capitalist class would not be eliminated and use of its property income for economically beneficial production would be strongly supported. As a capitalist class would exist part of its property income would inevitably be used for luxury consumption not investment. But such luxury consumption should be minimised – which also means in terms of mass public opinion and political policy it would be regarded as socially undesirable and not applauded. For the reasons already given this is both socially desirable and economically efficient. It is also entirely in line with Marx – and rational Western economic theory.

Conclusion

Finally, to emphasise once again, the fact that this article has focussed on the strictly economic aspects of Common Prosperity, and the errors of the attacks on it, is not because the present author considers that these specifically economic aspects are exclusively the most important. On the contrary, Common Prosperity embraces a much wider range of issues in China’s “people centred” development strategy than simply the economy.

Equally, views such as Soros’s are to be rejected for much more fundamental reasons than their basic errors of both economic fact and economic theory. Soros’s is repellent for several wider reasons. Soros is openly hostility to “distributing the wealth of the rich to the general population” – Soros clearly considers wealth should be concentrated among the rich. This is, first, objectionable from the point of the society’s wellbeing, second, for the reasons already analysed, it is economically inefficient, and third it will inevitably lead to serious social and political instability – as is vividly demonstrated in the recent political period in the U.S..

Also, obviously, the policy issues dealt with in this article are not the only major ones China’s government is currently dealing with regarding economic structure. It is important to see the effective action being taken against the negative consequences of private monopolies, on dealing with socially divisive forms of private education, of insufficiently regulated use of Big Data etc. But, nevertheless, the use of capitalist property income not for economically beneficial investment but for luxury consumption (in the strict technical sense of the term and not merely its everyday sense] is a very serious one in terms of economic scale. Furthermore, many of the other negative features which are being dealt with are in strict economic terms forms of luxury consumption or are ideological manifestations of it.

Just to illustrate the scale of this issue, as was noted in the case of the U.S. the increase in dividend payments by companies, which were not used for investment, between 1974 and 2020 was equivalent to 3.3% of U.S. GDP – or approximately $750 billion at today’s U.S. prices. Redistribution of this to the necessary consumption of the U.S. working class and ordinary population would have increased the income of the average household in the U.S. by over $5,700 a year – a significant increase in living standards. Alternatively, redistribution of this luxury consumption into fixed investment would have increased gross fixed investment in the U.S. by 15%, and net fixed investment by an astonishing 68%, allowing a significant increase in the rate of economic growth and therefore improvement in living standards. Alternatively, a combination of both increased consumption by the population and increased investment could have been pursued.

In summary, minimising use of income from capital for luxury consumption, rather than than property income being used for investment, is a very serious economic issue both in the U.S. and in China – precisely as Marx analysed. Similarly, for reasons analysed above, the comparison made in the Chinese media, to Scandinavian model of income and use of wealth distribution is not unreasonable – but of course in China it would be based on socialist and not capitalist economic and political foundations. Common Prosperity is not only socially just but, as already analysed, it is therefore in line with both the facts of economic development and with economic theory.

Common Prosperity precisely provides the framework for analysing the relations between the economy, society and politics in China’s post-1978 economic structure. It does so in a way which is both strikingly innovative from the point of view of the practical issues it deals with and simultaneously builds on and is entirely consistent with Marxism.

In summary, Common Prosperity is good for socialism in China – and it is good for China’s economy.

This article was originally published in Chinese at Guancha.cn.

18 October 2021

[1] Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1845). The German Ideology. In K. Marx, & F. Engels, Marx and Engels Collected Works (1976 ed., Vol. 5, pp. 19-539). London: Lawrence and Wishart p32. Section on “Production and Intercourse, Division of Labour and Forms of Property – Tribal, Ancient Feudal.

[2] Marx, K. (1867). Capital (Collected Works Lawrence and Wishart London, International Publishers New York, 1996 ed., Vol. 35). (S. Moore, & E. Aveling, Trans.) p730. Chapter 32 “Historical Tendency of Capitalist Accumulation”

[3] Stalin, J. (1951, November). Economic Problems of the USSR. Retrieved from Marxists.org: https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1951/economic-problems/ch01.htm . Section on ”Commodity Production Under Socialism”

[4] (Xi, Jinping Uphold and Develop Socialism with Chinese Characteristics, 5 January 2013.

[5] (Marx, K, Capital Volume 2 Chapter 20, section 4 Exchange Within Department Ii. Necessary Means Of Subsistence And Luxury Items)

Excellent, concise and persuasive analysis. I just can’t see how one could not agree. Common Prosperity paves the way of China’s Great Road to communism for the whole humanity

Figure 2, above, is missing the trace for China, though China is referenced in the title.