Introduction

Since 2 April, the absurdely misnamed “Liberation Day”, Trump has announced generalised U.S. tariffs against almost all countries and in particular China. The underlying goal of all these announcements was to attempt to end the U.S.’s huge continuing lag in economic growth compared to socialist China – the facts on this, as opposed to the entirely fallacious propaganda in much of the U.S. media, were set out in the earlier article “China’s economy in 2024 continued to far outgrow the U.S.”

Trump’s tariff policies cannot succeed in this objective – for reasons analysed in this article. As will be seen the Trump administration has no accurate understanding of the forces which determine the U.S. economy’s growth rate. The present article, therefore, first analyses why Trump’s tariff policies will inevitably fail in their objective and second the only means by which Trump could actually speed up the U.S. economy – with the geopolitical, and domestic U.S. political consequences of any attempt to achieve this.

Trump’s real tactic, as will be set out in detail, is to defeat the U.S. people, to sharply increase the rate of exploitation of them, and to use this victory to attack China. It follows from this that it is in the interests of both the population of the United States, and the Chinese people, for the American people to defeat this attack. There is, therefore, a direct coincidence of interests between the Chinese people and the American people, and a direct contradiction between both and the interests of the U.S. capitalist/imperialist class currently led by Trump. The ally of the American people is the Chinese people, and the enemy of the American people is the American capitalist class – not vice versa. Regarding the U.S. Karl Liebknecht’s famous words “the main enemy is at home” is therefore not only magnificent rhetoric but an entirely objective analysis of the U.S. economic situation.

In addition to outlining this general feature of the situation this article looks in detail at some specific areas, notable military spending and the U.S. health system in which this contradiction particularly acutely manifests itself.

What determines the growth rate of the U.S. economy

A previous article in this series, “Trump 2.0 and China – the real situation of the U.S. economy”, analysed the state of the U.S. economy as the second Trump presidency begins its attempt to cut China’s lead in economic growth by accelerating the U.S. economy – the parallel attempt by Trump to achieve a reduction in China’s growth lead by slowing China’s economy was analysed in “China’s economy in 2024 continued to far outgrow the U.S.”.

The factual data in that first article showed that in practice the only way the U.S. can accelerate its underlying, that is its medium/long term, economic growth is by increasing the percentage of fixed investment in U.S. GDP. In strict technical terms this is by increasing the percentage of net fixed capital formation in U.S. GDP – net fixed capital formation is new fixed investment minus depreciation of existing capital. The economic facts demonstrate that while in purely abstract theoretical terms other methods to accelerate U.S. economic growth might seem to be available, in reality these will not work (a formal explanation of this is given in the Appendix).

As will be seen, this economic fact immediately interrelates with the U.S. domestic political situation facing Trump as well as the geopolitical situation of the United States.

Section 1 – The incoherence of Trump’s tariff policy

The reasons for the deep interrelation between attempts to speed up the U.S. economy and U.S. politics/geopolitics is that the level of fixed investment in the U.S economy cannot be increased without increased sources of finances for this and the social transfer of resources necessary to achieve this.[i] This necessarily requires an increase in “capital creation”, to use Marxist economic terminology or an increase in inputs of total “savings”, using the terminology of Western economics – it should be noted that in economic terms “savings” includes not only household savings but also savings by companies and by the state (the latter being typically negative).

Indeed, in the case of the U.S., household savings are a small part of total savings – being only 3.7% of Gross National Income (GNI) out of a total of 17.7% of GNI for total gross savings. By far the largest factors affecting U.S. savings/capital creation are companies and the U.S. state – and, in the case of calculating net savings, the depreciation of capital by the U.S. company sector. Therefore, where are such capital/savings necessary to increase U.S. net fixed capital formation, and consequently GDP growth, to come from?

In analysing this issue it is unnecessary for present purposes to discuss whether savings create investment, or investment cause savings (as in the “Keynesian” framework), or some other factor(s) determine both. It is merely sufficient to note that an increase in investment necessarily requires an exactly equivalent increase in savings/capital creation. That is, Trump cannot increase the level of investment without increasing the amount of saving/capital creation available to the U.S.

To study the geopolitical dynamics this creates, it should then be noted that domestic U.S. fixed capital formation can be financed not only from U.S. domestic sources but also international ones. That is, an increase in U.S. fixed capital formation can be financed from:

- U.S. domestic capital/savings.

- Savings/capital created by other countries.

This fact determines the geopolitical implications of U.S. policy choices. Both sources must be analysed in terms of their relative quantitative importance, and of the political and geopolitical implications of the policy choices taken regarding them. Analysing these facts leads to a clear understanding of Trump’s policy.

Domestic and international sources of finances for investment

Starting with the largest source of savings/capital creation for investment this in the U.S., as in every major economy, is domestic and this will therefore be analysed first.

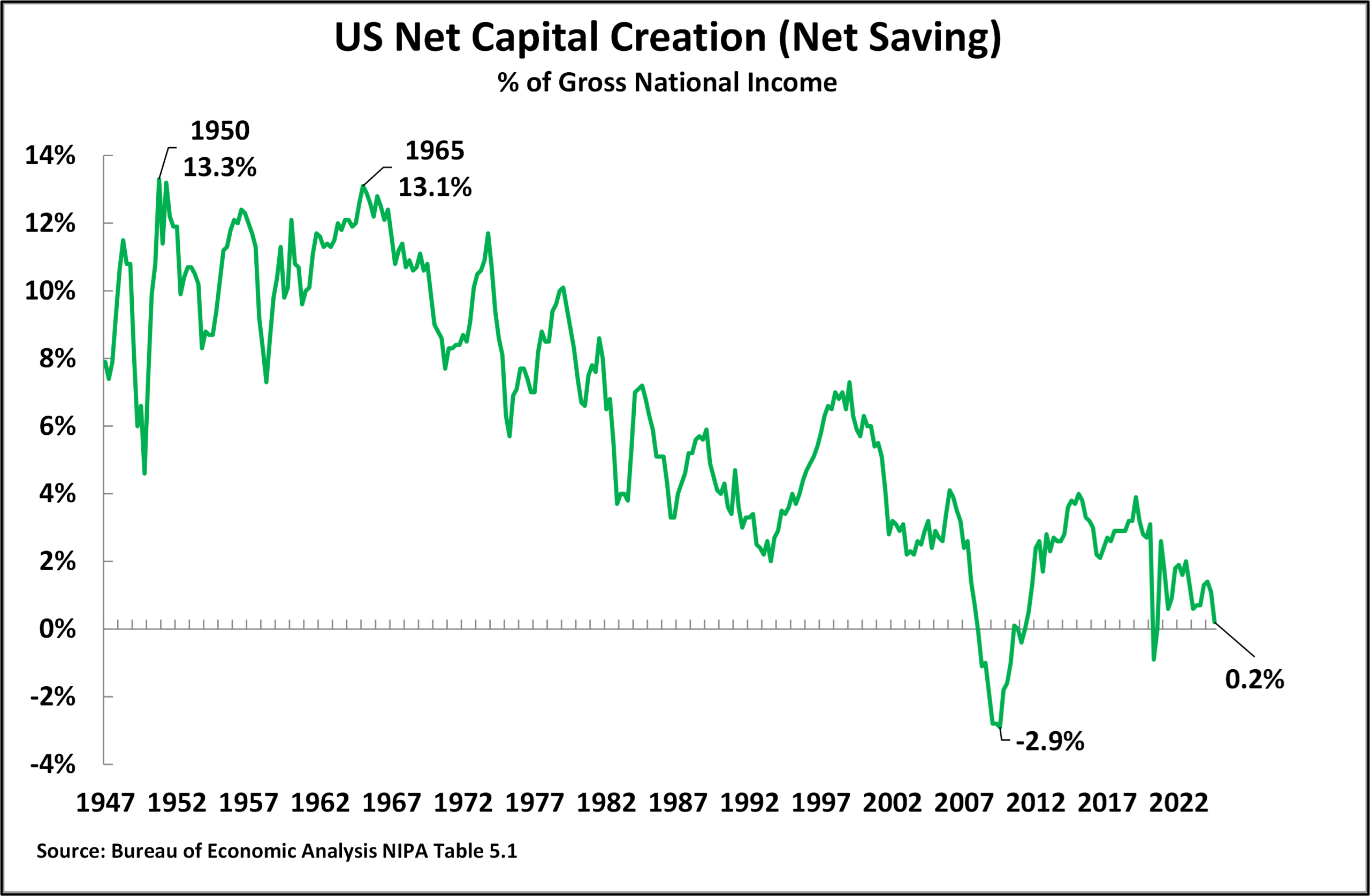

Figure 1 therefore shows the percentage of the U.S. economy accounted for by net savings/capital creation since the immediate post-World War II period. The trend is clear. Until the mid-1960s the percentage of net savings/capital creation in U.S. Gross National Income (GNI), in overall terms, was relatively high and fell only slightly – from 13.5% of GNI in 1950 to 13.1% in 1965. However, after the mid-1960s an almost six decades long profound decline of the percentage of capital creation/savings in the U.S. economy began.

By the time of the latest data at the time of writing, for the third quarter of 2024, net fixed savings/capital creation was only 0.2% of U.S. GNI, which is close to zero. The domestic U.S. economy in net terms was therefore, by the end of this period, generating almost no increase in capital – almost all U.S. domestic capital creation was simply replacing consumption of existing fixed capital (depreciation). The fall in the percentage of net fixed capital investment in U.S. GNI between 1965 and 2024 was a huge decline from 13.1% to 0.2% of GNI – a drop of 12.9%. of GNI.

The result is therefore that, on the basis of domestic resources, the U.S. is generating almost no net capital creation/savings. It is paradoxical, but true, that the world’s number one capitalist country in net terms is producing very little capital! If domestic capital/creation was the only source of financing of U.S. net fixed capital formation then the latter would collapse to almost zero. Given the extremely close correlation between the percentage of net fixed capital formation in U.S. GDP and the growth rate of GDP, shown in the article “Trump 2.0 and China – the real situation of the U.S. economy”, the growth of the U.S. economy, would similarly decline to almost zero.

Figure 1

International financing of U.S. capital investment

But, to understand the choices facing Trump, it should be noted that U.S. investment can be financed not only from domestic sources but by using capital produced by other countries. To then measure accurately how much such use of foreign produced capital can supplement, or substitute for, U.S. domestic savings/capital creation it is necessary to understand a fundamental, inescapable, but simple relation in economics. This is that, by definition, the inflow/outflow of capital from a country is necessarily exactly equal to the current account of its balance of payments with the sign reversed: that is, a balance of payments deficit means a net inflow of capital into a country and a balance of payments surplus means a net outflow of capital from a country.[ii]

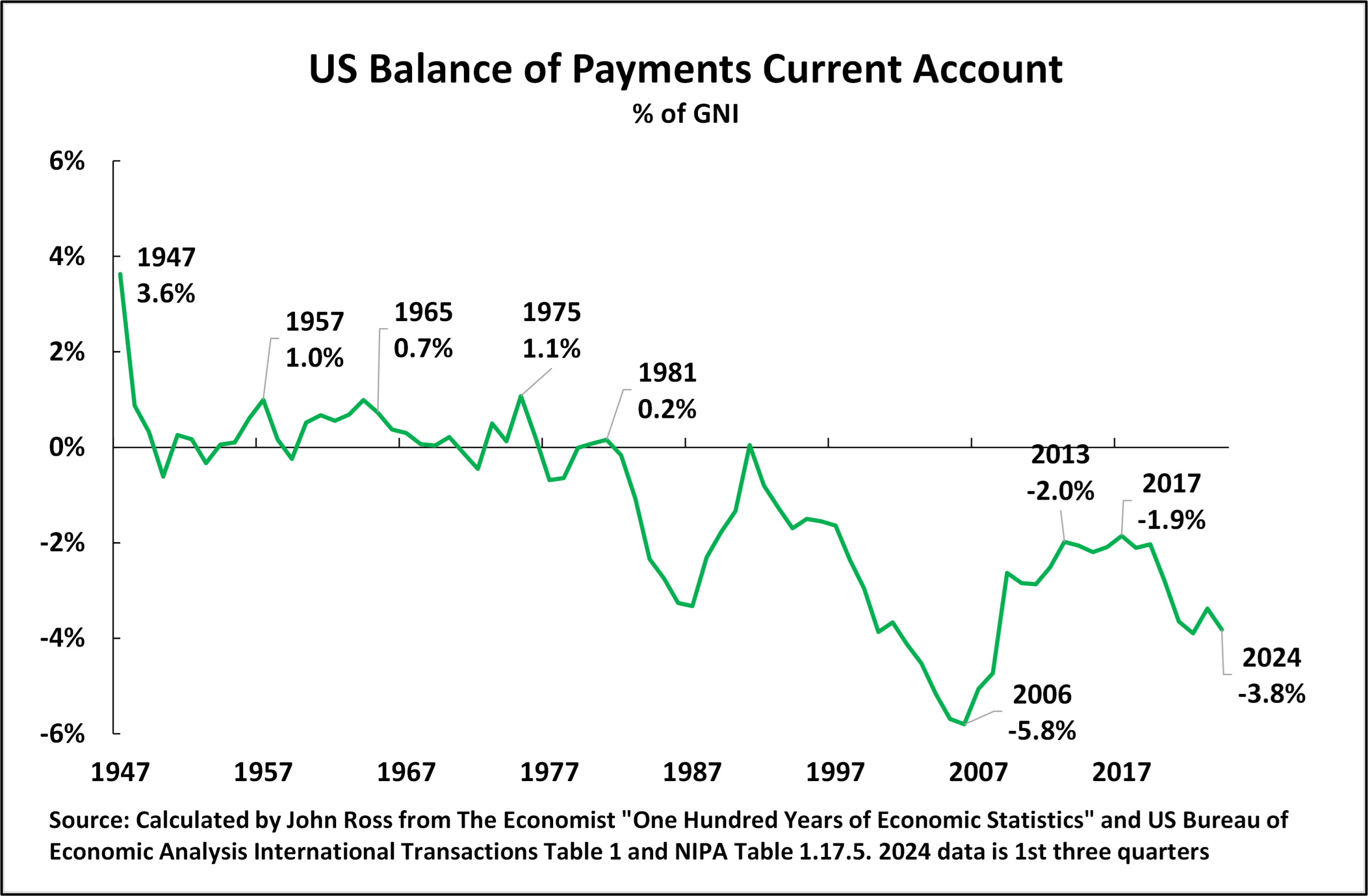

Bearing this inescapable relation in mind, Figure 2 shows the post-World War II U.S. current account of the balance of payments. As may be seen, until 1981 the U.S. balance of payments, with a few exceptions, was each year in surplus – that is, until 1981, the U.S. was a net capital exporter. After 1981 the U.S., in contrast, developed a virtually permanent balance of payments deficit – that is, the U.S. was using capital created by foreign countries for its own investment.

Taking the same periods as those for domestic savings/capital creation considered above, between 1965 and the 2024 the U.S. balance of payments changed from a surplus of 0.7% of GNI to a deficit of 3.8% of GNI. That is, the U.S. changed from exporting to other countries capital equivalent to 0.7% of GNI to obtaining capital from other countries equivalent to 3.8% of GNI – a total shift of 4.5% of GNI. This use of capital produced by other countries is therefore what allowed the U.S. economy to escape the consequences of the fact that its own domestic capital creation was extremely low – and was sufficient for the U.S. economy to maintain a low average growth rate, an average of slightly above 2%, rather than experience actual stagnation. This use of capital created by other countries therefore meant that U.S. domestic investment could be higher than U.S. domestic capital creation/savings.

Figure 2

Use of capital created by other countries cannot adequately compensate for the decline of capital created in the U.S.

Regarding the possibilities to significantly speed up the U.S. economy, however, comparing the data for the decline of U.S. domestic savings/capital creation with that for inflow of capital, makes it clear that the use of capital created by other countries was and is not large enough to fully compensate for the decline in U.S. domestic capital creation/savings or to greatly close the U.S. lag compared to China in terms of economic growth rate.

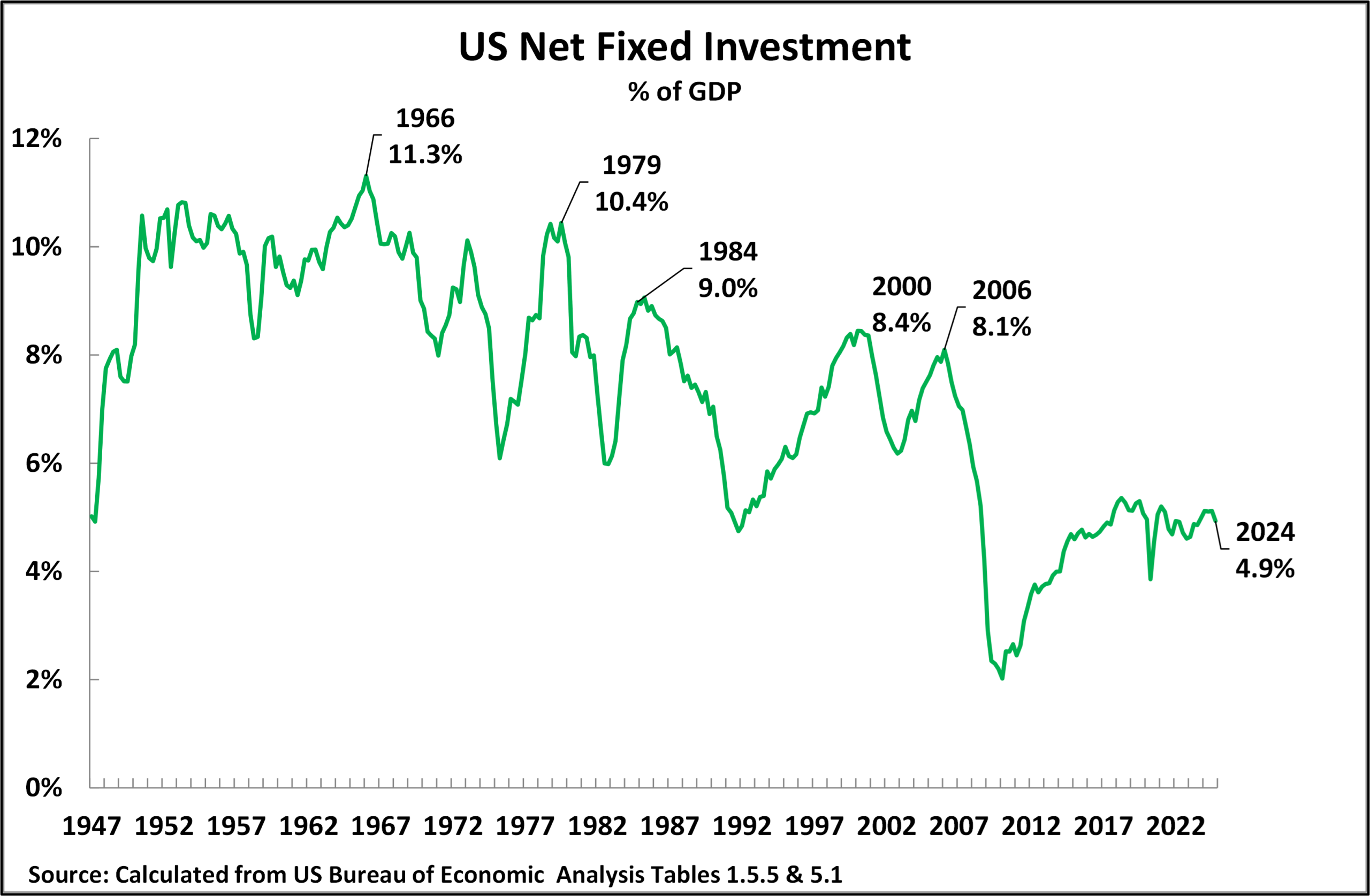

To be precise, between 1965 and 2024 U.S. domestic savings/capital creation fell by 12.9% of GNI, but the turnaround in the same period of 4.5% of GNI from a capital outflow to a capital inflow was sufficient to only offset approximately one third of this fall. As capital obtained from foreign countries was insufficient to offset the decline in U.S. domestic capital creation/savings, therefore U.S.net fixed capital formation had to, and did, fall – Figure 3 shows the decline in U.S. net fixed capital formation from a post-World War II peak of 11.3% of GDP in the 1st quarter of 1966 to 4.9% of GDP by the 4th quarter of 2024.

Figure 3

Given the extremely high correlation between the percentage of net fixed capital formation in the U.S. economy and rate of GDP growth the inevitable result of this was the progressive slowdown in the rate of U.S. GDP growth, from 4.4% in 1969 to 2.1% by 2024 – shown in Figure 4 below. It is this slowdown in the U.S. growth rate which is the most fundamental problem facing the U.S. in its attempt to suppress China.

This inflow of capital into the U.S. reached a peak of 5.8% of U.S. GNI in 2006. The U.S. therefore became deeply dependent on capital from abroad for its own growth. But if other countries supplied capital to the U.S., via running a balance of payments surplus with it, this meant they could not use this capital for their own national development. The resulting imbalances and tensions were one of the causes leading to the 2008 international financial crisis. In turn, this crisis’s violent impact forced a reduction in the U.S.’s use of capital from other countries as the U.S. moved into recession – by 2013 the inflow of capital from abroad into the U.S. had fallen to 2.0% of GNI. U.S. import of capital then remained at approximately this level until 2017, when it was 1.9% of GNI, before it began to rise sharply again – reaching 3.8% of GNI on the latest available data at the time of writing, for the first three quarters of 2024.

U.S. economic growth during the last seven years was therefore aided by use of capital generated by other states, but this was not on a scale sufficient to compensate for the fall in U.S. domestic capital creation.

Figure 4

The failure of U.S. manufacturing “reshoring”

There was and is, however, is an inevitable macroeconomic and political consequence of what is now the long-term U.S. partial reliance on capital from abroad. As the inflow of foreign capital is exactly equal to the U.S. balance of payments with the sign reversed, therefore a net inflow of capital from abroad necessarily means that the U.S. must run a balance of payments deficit. In turn, by far the largest component of the balance of payments is visible trade. Consequently, if the U.S. makes large scale use of foreign capital it must run a wide deficit in goods trade – the U.S. must have large scale imports of industrial and manufactured goods. The competition from these, their replacement of goods that could be produced domestically, therefore puts downward pressure on U.S. industrial and manufacturing production.

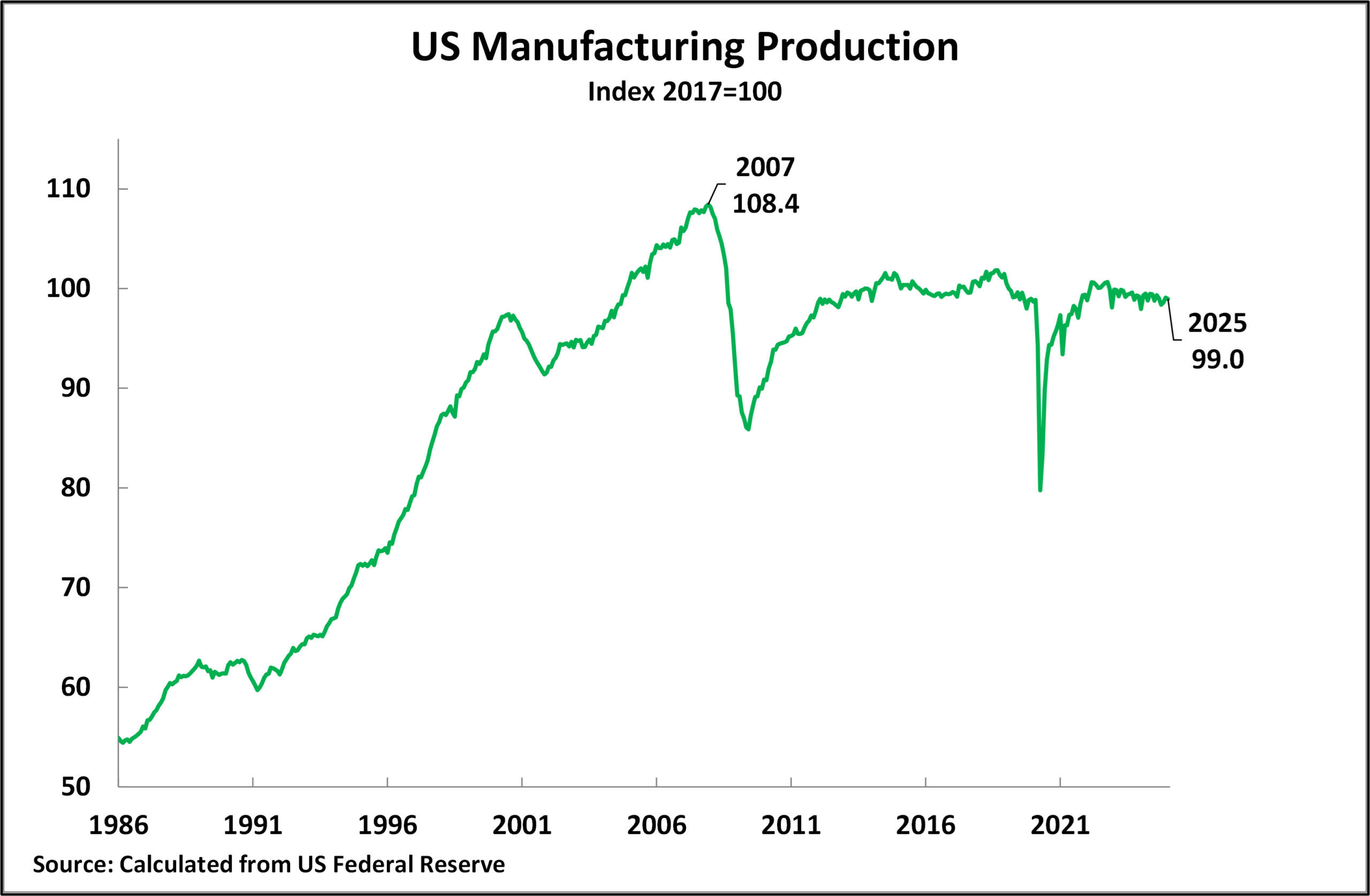

It is for this reason that the attempt of “reshoring” of U.S. manufacturing production has been a 100% failure. As Figure 5 shows U.S. manufacturing production is now significantly lower than it was 17 years ago – in January 2025 it was 8.7% below its peak in December 2007.

Figure 5

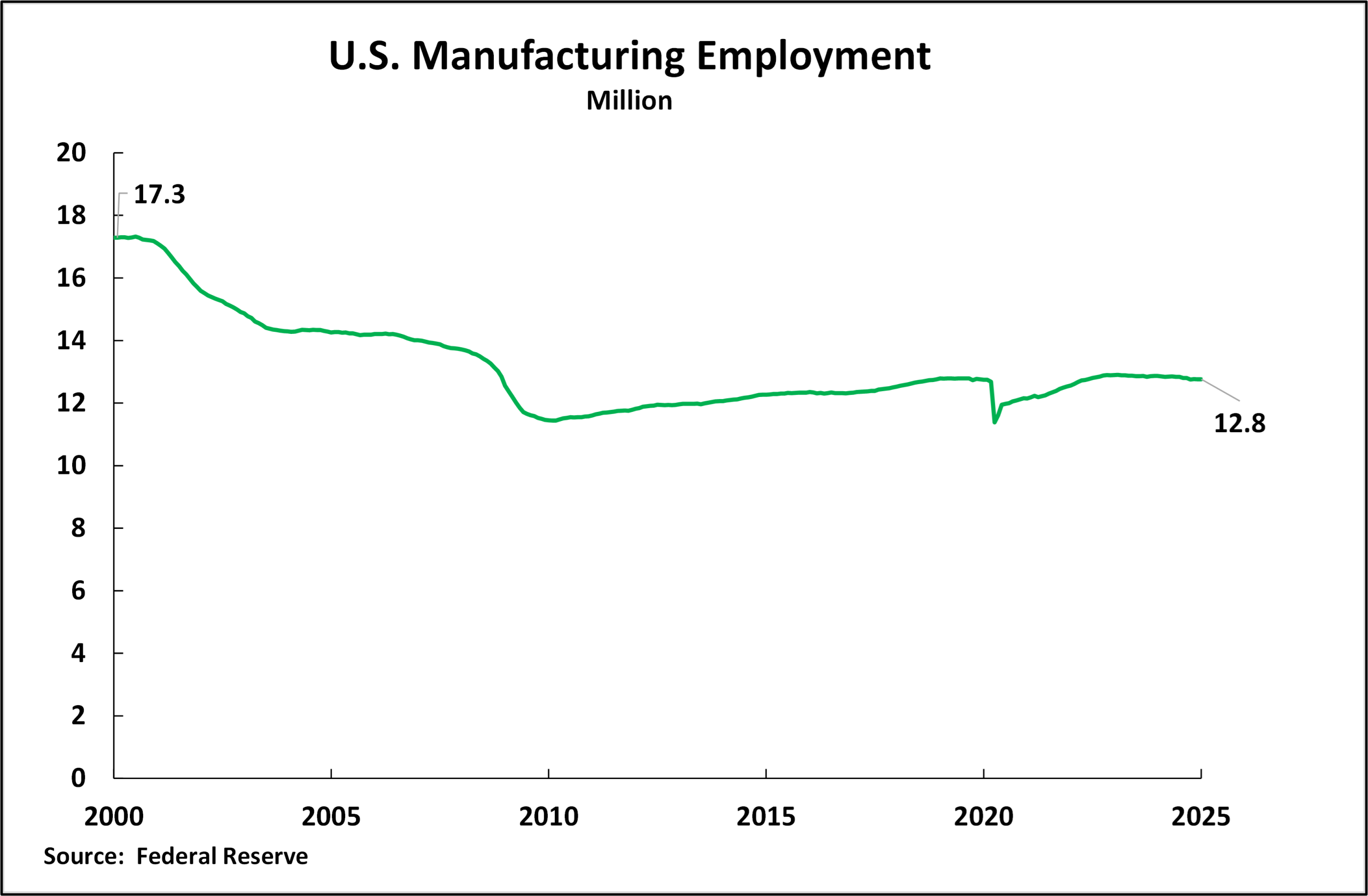

The political consequence of this decline of U.S. manufacturing production is also clear and its result widely known. It propelled the extension of the notorious U.S. “rustbelt”, that is the wiping out of jobs in entire traditional manufacturing regions in the U.S.. Figure 6 illustrates that in showing that since 2000 U.S. manufacturing employment has fallen by over a quarter, by 26%.

It is allegedly to attempt to reverse this complete failure of “reshoring” by U.S. manufacturing industry, accomplishing which the forces around Trump consider crucial for the U.S. economy, that Trump is introducing protectionary trade tariffs – and it is to devastated American working class communities that Trump demagogically attempted to appeal politically.

What, therefore, are the chances of Trump reversing this situation – to significantly increase the rate of growth of the U.S. economy and thereby re-establish U.S political stability, by means of his tariff policy?

Figure 6

The contradictions of Trump’s tariff policy

The above international relations in fact make clear why the means, tariffs, by which Trump has chosen to attempt to revive U.S. economy are self-contradictory, and incoherent in the understanding of the interrelation between tariffs and U.S. growth – but with inevitable geopolitical consequences and political side-effects within the U.S..

Some of these immediate macroeconomic effects of Trump’s tariff policy are generally known. As is by now widely understood, by tariffs increasing the price of the imported goods and services on which they are levied this is directly inflationary. In terms of the indirect consequences of this, these tariffs would allow U.S. domestic producers of these goods and services to increase their prices while remaining competitive – which would also be inflationary. Therefore, the short-term effects of the tariffs would be directly and indirectly inflationary – reducing U.S. living standards via these means. U.S. opinion polls showing the majority of the population opposing Trump’s tariff policies indicate a widespread understanding of this.

But it is not so widely understood, but will become apparent, what would be the knock on consequences. It would, other things remaining equal, put upward pressure on short-term interest rates if the Federal Reserve decided it was necessary to respond to inflation by raising these – or reducing its anticipated rate of lowering them. It would also put upward pressure on long term interest rates if purchasers of U.S. bonds decided they would require higher nominal interest rates to compensate for higher inflation. Such higher sustained interest rate rises, in addition to other factors, would tend to slow the U.S. economy – which, other things remaining equal, would reduce inflationary pressures. That is, the short-term inflationary effect could be offset by slower economic growth.

Such slower growth is itself clearly not desirable. What would be the exact eventual combination of inflation, slower growth and higher interest rates would be determined by the overall economic situation – but these would simply be different combinations of negative effects.

Still more fundamentally contradictory is the consequences of Trump’s trade policy for the most powerful factors affecting U.S growth analysed above. Trump’s declared intention is to use tariffs to reduce the U.S. trade deficit. However, as already noted, the overwhelmingly largest factor in the U.S. balance of payments deficit is the trade deficit – in 2023, the latest year with full data at the time of writing, U.S. trade in goods and services accounted for 87% of the U.S. balance of payments deficit. As a result, any significant success in reducing the U.S. trade deficit would produce a significant reduction in the U.S. balance of payments deficit.

But, as the balance of payments deficit is exactly equal to the inflow of capital, reducing the balance of payments deficit would reduce the inflow of capital into the U.S.. Consequently, unless there were an equal or greater increase in U.S. domestic capital creation/savings, reducing the U.S. trade deficit would reduce the finance for U.S. net fixed capital formation And, due to the extremely close correlation between the percentage of net fixed capital formation in GDP and GDP growth, so also would U.S economic growth slow down.

In summary, regarding Trump’s tariff policy.

- Trump’s aim is to lessen the U.S. trade deficit which, as trade is the largest component of the U.S. balance of payments, means reducing the U.S. balance of payments deficit. That, however, means lessening the inflow of capital into the U.S.. Unless other domestic counteracting processes take place, reducing the U.S. balance of payments deficit will reduce the capital available for investment in the U.S. and slow its economy. This process will also create trade tensions with other countries as the U.S. imposes tariffs and other countries retaliate.

- However, if the U.S. use of capital from abroad to finance its investment does not fall then, other things remaining equal, the U.S. can maintain its investment level. But its balance of payments deficit will not be cut and, given trade is the large component of the balance of payments deficit, it is in practice impossible to reduce the U.S. balance of trade deficit.

Section 2 – The reasons Trump 2.0 is compelled to choose a major attack on U.S. living standards

Capital from abroad is insufficient to offset the decline in U.S. domestic savings

Which of the two above processes regarding the U.S. trade and balance of payments deficit will take place, or whether the situation of the U.S. economy regarding the use of capital created by other countries, will remain essentially the same as at present, is as yet unclear. However, there is a more fundamental issue both in terms of economics and its consequences for U.S. domestic politics. This is whether any practically conceivable inflow of capital from abroad, and corresponding change in the U.S. balance of payments, can by itself be enough to lead to a major revival speeding up growth of the U.S. economy? The answer to this is no, and fundamental geopolitical and domestic U.S. political consequences flow from this.

To see why this is the case, note that the latest data for the U.S. balance of payments deficit at the time of writing is that it is 3.8% of GNI. The maximum ever U.S. deficit was 5.8% of GDP in 2006 – this was the culmination of the almost continuous increase of the U.S. balance of payments deficit from the early 1990s and during the early 2000s. This 5.8% of GDP deficit was so large that it destabilised the international financial system and was one of the key factors leading to the international financial crisis which developed during 2007 and exploded in 2008.

Even if the U.S. balance of payments deficit could at present be sustainably widened again to this peak level, which is highly doubtful given the crisis that was produced the last time such a deficit was reached, it would only add a 2% of GDP inflow of capital to the U.S. – the U.S use of capital from abroad would increase from 3.8% to 5.8% of GNI. The widening of the U.S. balance of trade deficit which would be necessary for this to occur would put strong downward pressure on U.S. manufacturing production and jobs – precisely the opposite of the goals set by Trump.

But, as regards the practical results of even such a scenario, the correlations demonstrated in “Trump 2.0 and China – Part 1, the real situation of the U.S. economy” show that to increase U.S. GDP growth by 1% a year the U.S. has to increase its net fixed investment by 3.5% of GDP (see in particular Figure 9 in that article). An increase in capital inflow from abroad of 2% of U.S. GDP would therefore increase annual U.S. GDP growth by only 0.67%. This would be useful but not nearly sufficient to close the gap in growth rates between the U.S. and China – the 10-year average GDP U.S. growth rate is 2.17%, so an increase of 0.67% would take this to 2.84%, which still lags far behind China’s latest 5.0% annual GDP growth rate. Consequently, for purely quantitative reasons, any increase in the level of U.S. capital investment to sufficiently close the gap in the growth rate between the U.S. and China cannot come from use of capital created by other countries but will have to come primarily from U.S domestic capital creation/savings.

Therefore, the crucial factual question is where are such U.S. resources to come from? As will be seen this determines their effect on U.S. domestic politics and also international geopolitics.

Trump failure to raising domestic savings

To understand the domestic political consequences of these economic processes recall that savings and consumption together constitute 100% of a domestic economy. Therefore, any increase in the percentage of the U.S. economy devoted to capital creation/savings necessarily requires an equivalent reduction in the percentage of the U.S. economy used for consumption. In examining the consequences of such a shift, therefore a key issue, in particular in terms of its political impact, is what forms of U.S. consumption could or should be reduced?

To analyse this, as a preliminary, it is necessary to note that in technical economic terms consumption has a wider meaning than what is referred to as “consumption” in everyday language – the latter focuses on household consumption such as food, housing, entertainment etc. But consumption in economic terms is simply any product or service which is used up which is not an input into production. Thus, to take a highly relevant example, military spending is a form of consumption – as military payments and equipment are not inputs into production.

If the percentage of the U.S. economy devoted to capital creation/savings is to be increased, and therefore the percentage devoted to consumption is to be reduced, the difference between these different forms of consumption clearly has huge consequences for U.S. living standards. If the proportion of the economy which is expenditure on food, housing, entertainment, travel, holidays etc is reduced this means a reduction in the proportion of the economy which maintains the living standards of the U.S. population. If, however, for example, military expenditure is reduced as a percentage of the economy, then, while there is an overall fall in the proportion of consumption in the economy, and, other things remaining equal, an increase in savings, this does not mean a fall in the proportion of the economy used to maintain living standards.

There are reforms which would greatly speed up U.S. economic growth with no reduction in the proportion of the economy used for the people’s living standards

Once this framework is analysed then the domestic economic choices facing Trump can be clearly understood. It is clear that there are policies in the U.S. which would increase resources for increasing savings/capital creation but which would not involve any reduction in the proportion of the economy which constitutes the basis of U.S. living standards. Regarding large sectors of the U.S. economy in particular these are:

- First, military expenditure. Official U.S. military spending is 3.7% of GDP, but in fact it is much higher – as significant parts of military expenditure are not recorded as such (e.g, military pensions are recorded as non-military spending, whereas in reality they are part of military expenditure). Thus, in 2022 a detailed analysis found that while the U.S. official budget showed military spending of $766 billion, in reality the figure was $1.537 trillion. Nevertheless, even the official 3.7% of GDP U.S. figure is far above the NATO target of 2% of GDP on military spending.

Reducing U.S. military spending from 3.7% of GDP to the 2.0% NATO target would release 1.7% of GDP for increasing net fixed capital formation with no decrease in the percentage of household consumption in U.S. GDP. The correlation already noted shows that to increase U.S. annual GDP growth by 1.0% the U.S. has to increase the percentage of net fixed investment in GDP by 3.5%. An increase in U.S. net fixed investment of 1.7% of GDP would therefore be expected to increase U.S. annual average GDP growth by almost 0.5%.

- A second key area is the extraordinarily inefficient U.S. private health system. The U.S. spends a far higher percentage of GDP on health than any other major advanced country. Taking the latest year for which there is internationally comparable World Bank data for both life expectancy and expenditure on health, 2021, U.S. health expenditure was 17.4% of GDP compared to 12.9% in Germany, 12.4% in the UK, and 12.3% in France. But U.S. life expectancy was 6.0 years less than France, 4.5 years less than Germany and 4.4 years less than the UK – U.S life expectancy was 76.3 years, France 82.3 years, Germany 80.8 years, and the UK 80.7 years. Therefore, the U.S. health care system means that it spends a far higher proportion of GDP on health than any other advanced economy but has a significantly lower life expectancy – an extraordinary inefficiency!

If the U.S. were able to achieve the same level of efficiency as Germany, for example, which would almost certainly mean replacing the U.S. private health service with a public one, that would release 4.5% of GDP which could be used to increase net fixed investment with no decrease in the proportion of the U.S. economy used for household consumption. The correlation that an increase in U.S. net fixed capital formation of 3.5% of GDP increases U.S. annual GDP growth by 1% means that this increase in net fixed capital formation of 4.5% of GDP would be expected to yield an increase in annual U.S. GDP of 1.3%.

Taking the two together, if both reduction of U.S. military spending to the level set for NATO, and replacement of the inefficient health system, were undertaken, together representing a combined 6.2% of U.S. GDP, and this was transferred to net fixed capital formation, this would be expected to approximately increase annual U.S. GDP growth by 1.8%. Adding this to the existing 10-year annual average U.S. GDP growth of 2.2% would be expected to lead to an annual average U.S. economic growth of 4.0% – taking the U.S. quite close to China’s 5.0%.

In summary the cause of the slow growth of the U.S. economy, the slow or non-existent growth of living standards, the growth of the rust belt etc is not China. It is in the final analysis the U.S. imperialist system, but in the most immediate sense it is the high level of U.S. military spending to sustain an aggressive foreign policy, a grotesquely inefficient health system to sustain private health interests, and similar factors.

It may, therefore, be seen that that purely economically there are no insuperable obstacles to substantially increasing the U.S. rate of economic growth without reducing the proportion of the economy devoted to U.S. household living standards. While, as a socialist, it would be nice to say that “only socialism provides a way out for the U.S.” in purely economic terms it is unfortunately at present not true – although there are other very strong reasons why socialism is required. There are reforms by which the U.S. could substantially increase its annual GDP growth without reducing the proportion of the U.S. economy that form the basis of U.S. living standards. Furthermore, as the growth rate of household consumption is strongly correlated with the growth rate of GDP, it would be expected that U.S. living standards would strongly rise as a result of such policies. But the above would be major reforms, requiring a sharp change in direction by the U.S. and not merely tinkering with the edges.

Why Trump will not implement such reforms

However, while such reforms in the U.S. are entirely possible economically, naturally they will not occur under Trump, and neither will they be fought for by the existing leadership of the Democratic Party – precisely because politically they would require large changes in overall U.S. policy.

- Reduction in military expenditure would require a much less aggressive foreign policy and less expenditure on wars.

- The U.S. is the only major advanced economy which has a private, as opposed to a public, health system. Reform of the U.S. health service, to make it as efficient as those in other advanced economies, would almost certainly require switching to a public health system – which would mean tackling private health care vested interests in the U.S. which have proved themselves to be extremely powerful.

Trump and U.S. military spending

The most immediate geopolitical and political consequences that flow from this reality concerning the U.S. economy relate to military expenditure, Trump’s announced aim is to maintain, and if possible increase, U.S. military supremacy – by means noted below. What the absolute level of U.S. military expenditure is, within that framework, a purely tactical question – provided U.S. military supremacy is maintained or increased. Trump could therefore, of course, in principle even consider making reductions in U.S. military expenditure, as these would allow an increases in the U.S. rate of economic growth, as analysed above, but only provided that these reductions would not challenge the military advantage enjoyed by the U.S.. This explains numerous of Trump’s initiatives in the foreign policy field.

The first is regarding the Ukraine war and Europe. Most immediately the U.S., understanding that NATO is losing the war in Ukraine, is attempting to create better relations with Russia – by means of which it also hopes to create greater distance between Russia and China. But the strategic framework of this is that the U.S. wants the West European states to increase military spending so that the U.S. can potentially decrease its military commitment in Europe and redeploy greater military resources against China. As U.S. Defence Secretary Hegseth said in his 12 February speech in Brussels to the Ukraine Defense Contact Group, announcing the new U.S. policy on the Ukraine war: “the U.S. is prioritizing deterring war with China in the Pacific, recognizing the reality of scarcity, and making the resourcing trade-offs to ensure deterrence does not fail… As the United States prioritizes its attention to these threats, European allies must lead from the front. Together, we can establish a division of labor that maximizes our comparative advantages in Europe and Pacific respectively.”

Of course, Hegseth’s talk about “deterring war” is hypocrisy – it is in reality a U.S. military build-up against China. But Hegseth makes clear that the U.S. wants no reduction of NATO’s power in Europe, but simply that the U.S. wants Europe to take a greater share of this so that the U.S. can redeploy a higher proportion of its military against China.

Second, Trump initially vaguely talked of 50% reductions in military expenditure by the U.S., China and Russia, which might superficially appear “peaceloving” – until its practical implications are analysed.

In the 1970s, when the U.S. and USSR had approximately equal military forces, such equal proportionate reductions in their military expenditures were appropriate – for example these were in fact embodied in the Strategic Arms Limitation (SALT) treaties, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty, and the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) treaty. But today the U.S. has far greater military expenditure than either China or Russia. Therefore, equal percentage reductions in U.S., China and Russian military spending would simply cement in place a U.S. advantage.

Indeed, such equal percentage reductions would probably significantly increase this U.S. military advantage as the Trump administration has already approved extremely expensive new projects, such as an “iron dome” for America in the form of a comprehensive missile defence system. This is in reality, in military terms, an attempt to create a U.S. nuclear “first strike capability – a “first strike capability” is one for a country to have an anti-missile system sufficiently strong to defeat the reduced number of nuclear weapons that would be left to another country to retaliate after a nuclear first strike had been carried out against it. In a similar step in this direction the U.S. has unilaterally withdrawn from both the INF and ABM treaties.

As the simplest way to defeat such an “iron dome” is to increase the number of missiles/nuclear warheads with which to attack it, then if the number of nuclear weapons/missiles were reduced by Russia and China, the U.S. would be more confident that its “iron dome” would be successful and therefore it would increase the U.S. temptation to launch a first strike.

Therefore, even in principle, let alone taking into consideration more practical issues, the only equitable military reduction proposals by the U.S. would be ones which left the U.S., Russia, and China with approximately equal levels of military spending. But this is precisely what Trump does not propose. Instead, he is simply using the world population’s desire for peace, and therefore its desire in general to keep military spending to the minimum, to conceal what are proposals to cement in place, or even increase, U.S. military dominance.

As Trump will only cut military spending in a way that would maintain or increase U.S. military dominance, and other countries are unlikely to agree to mutual cuts in military expenditure in a form that maintains or increases U.S. military supremacy, in practice therefore Trump will not reduce U.S. military spending – as shown by his latest defence budget proposals.

The situation of the Democratic Party leadership

This objective economic situation also determines the fundamental position of forces within the Democratic Party – the more detailed situation of U.S. politics can of course only be seen from within the United States. The Democratic Party leadership has no significant difference in policy on military spending with Trump/the Republicans – it has habitually not only supported U.S. imperialist foreign policy and ideology but voted in favour of increases in U.S. military spending, thereby reducing the U.S. working class’s ability to defend living standards. That is, not only in its ideology but in its practical measures the leadership of the Democratic Party carries out no break with the policies of U.S. imperialism. This has been a key factor leading to the stagnation of U.S. living standards and also Democratic Party electoral defeats such as those of Biden/Harris. With such an orientation even if the scale of attack Trump will necessarily launch against the U.S. working class leads to the return of a Democrat administration that will both attack the oppressed internationally and the U.S. working class domestically, as did the Biden administration, leading to the type of demoralising defeat suffered by Harris.

Right wing authoritarianism and the Democratic Party left

The objective economic situation of the U.S., the almost complete disappearance of domestic net U.S. capital accumulation, and the inability of use of foreign capital to substitute for it on a scale capable of producing anything other than an anaemic growth rate objectively destroys the basis of both centre-right (“traditional Republican) and centre-left (Democratic Party leadership) politics in the U.S..

The way out of that situation proposed by the “rightward break” from the U.S. political centre, by the forces around Trump, is replacement of the U.S. political system as it has historically been configured with a right-wing authoritarianism. Very serious U.S. ruling class forces are now organised around such a project – the current processes which reflect this project are sufficiently well known not to need describing in detail here. This would accompany the increase in the rate of exploitation of the U.S. working class, the necessity of which is analysed above, and would constitute a tremendous historical defeat of the American people – with great dangers for the entire world in the invigorated U.S. imperialist project it would represent. Reciprocally, defeats suffered by this U.S. imperialist project internationally would weaken and destabilise it within the U.S. – to the advantage of the U.S. people.

The only “leftward break” from the U.S. political centre with mass support, forces such as those represented by Sanders and AOC, is much weaker both ideologically and organisationally than the right-wing break with the centre. In terms of their ideology Sanders/AOC are easily identified as a form of “social imperialism”. That is, they stand for an improvement in the living conditions of the U.S. working class but do not break with U.S. imperialism in its attacks on the oppressed of other countries – as shown clearly in their refusal in practice to break with Israel, their de facto support for the war in Ukraine which was caused by the expansion of NATO etc. But an attitude to political currents cannot be determined most fundamentally by their ideology but by their practical positions. On some practical policies, such as the level of military budgets, whatever their other policies, Sanders/AOC do oppose the immediate practical policies of U.S. imperialism.

U.S. budget clashes on health spending

Turning to the U.S. health system, it is unnecessary to explain here that Tump will undertake no U.S. health care reform in his second term.

What, however, the objective situation of the U.S. economy and Trump’s economic policies, as they are implemented and go through Congress, will unleash will be a struggle over the level of health spending in the U.S. This is extremely well known and, as the Washington Post analysed the first vote in the U.S. House of Representatives on this: “The… vote of 217 to 215 teed up a bitter fight… over which federal programs to slash to partially finance a huge tax cut that would provide its biggest benefits to rich Americans…

“The blueprint… calls for slashing $2 trillion in spending… without specifying which programs should be cut, though top Republicans have targeted Medicaid and food aid programs for poor Americans. And it directs increases of about $300 billion for border enforcement and defense programs…

“Republicans in swing-seat districts had said that they would be uncomfortable approving a plan that could lead to major cuts to Medicaid and food stamps.

“The plan instructs the Energy and Commerce Committee, which oversees Medicaid and Medicare, to come up with at least $880 billion in cuts. While some Republicans denied that they would slash programs for the poor, the amount of revenue they are calling to raise would all but certainly necessitate some cuts to at least one of those programs…

“Democrats see the Medicaid cuts that are likely to be included in whatever legislation House Republicans put together as a salient line of political attack, akin to their efforts to campaign in 2018 on the G.O.P. efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act [“Obamacare”].

“’It has to come from Medicaid, it has to come from the A.C.A. [Affordable Care Act] premiums,’ said Representative Brendan Boyle of Pennsylvania, the top Democrat on the Budget Committee, ‘because that’s the only place you can find $880 billion.’”

Consequences of Trump’s refusal to cut military spending or reform health care

If reduction of military expenditure and reform of the U.S. health system are excluded by Trump, then increases in the level of investment in GDP in the U.S., and the reduction in the level of consumption, can in practice only be carried out by reducing the proportion of the U.S. economy devoted to household consumption and social security. This means, at least in the short term, an attack on U.S. living standards which would undermine Trump’s political support in the same way that the reduction of U.S. real wages under Biden destroyed the popularity of his presidency – that data on the fall in U.S. real wages are given in “Trump 2.0 and China – the real situation of the U.S. economy.” Trump’s own first presidency, as with Biden’s, was ended by his low level of popular approval, due to the consequences of very slow U.S. economic growth, and with this catalysed, in the case of Trump, finally by the huge wave of popular protests, following the racist murder of George Floyd – this combination led to an enormous electoral turnout of the black population, and other social layers, to vote against Trump in the 2020 presidential election.

Therefore, as Trump refuses in practice either to cut the percentage of the U.S. economy spent on the military or the extraordinarily inefficient health system, and given that the only way that the U.S. economy can be accelerated is by increasing the percentage of GDP used for net fixed investment, the only way that Trump can find the finances to attempt to speed up the U.S. economy, is to reduce the proportion of the U.S. economy used to maintain U.S. living standards. This reality forms the inextricable link between U.S. economic policy and its politics and geopolitics.

Section 3 – the geopolitical implications of Trump’s policies

What are the Implications of these processes for U.S. geopolitics and foreign policy and therefore for other countries – including China? The geopolitical effect of tariffs are well known and therefore need not be discussed here – they will simply increase the clashes of other countries with the U.S.

The most immediate, and most important, interrelation of the domestic political consequences of Trump’s policies with U.S. geopolitical relations is that the more successful the resistance to Trump’s attempt to cut U.S. living standards the less room this will leave for Trump to increase military spending. This is, in a different form, the same process as in previous U.S. post-World War II wars and military build ups – this economic and political pattern of the U.S. increasing military expenditure as a proportion of GDP during military build ups, and then it being forced to reduce this as a result of defeats in war combined with popular opposition in the U.S., is shown in Figure 7.

- Around the Korean war the combination of China’s military defeats of U.S. forces in Korea, with the strain the military build-up placed on the U.S. economy, led Eisenhower to the conclusion that the war must be ended. This strategic defeat was followed by a reduction in the proportion of the U.S. economy used for military purposes which lasted until the beginning of the 1960s

- The proportion of military spending in the U.S. economy was then again increased for the war in Vietnam. But the combination of Vietnamese military resistance, aided by China and the USSR, together with the economic cost of the war, destroyed Johnson’s popularity, created political turmoil in the U.S., and led Nixon to the conclusion that to stabilise the situation he had to seek détente with China and bring the war to an end.

- The U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, which was initially strongly popular, later became wildly unpopular and, after the international financial crisis, to which the peak reliance of the U.S. economy on capital from abroad contributed, as analysed above, the U.S. was forced to reduce the percentage of its economy devoted to military spending.

- As may be seen from Figure 7 U.S. military expenditure is currently at the lowest level as a percentage of GDP since World War II, but with Trump indicating he wants an increase in military spending for policies such as the projected “iron dome” which is part of a policy of confrontation with China. The more successful is resistance to reductions in U.S. living standards the less room will be left to Trump to increase military spending.

Resistance by the U.S. population to the attacks on living standards, which are required by Trump’s policies, are therefore objectively in the interests of all countries threatened by the U.S..

That is, the domestic political situation in the U.S. and the geopolitical situation are inextricably connected.

Figure 7

Conclusion

To summarise, as noted in the earlier article “Trump 2.0 and China – the real situation of the U.S. economy”, it is not of any great interest to attempt to assess what are Trump’s subjective intentions, and it is actively misleading and damaging to fail to analyse accurately the real state of the U.S. economy – that is, to believe Trump’s and the U.S. media’s propaganda. Analysis of the objective situation of the U.S. economy, and the fundamental factors which determine its development, leads to the following clear conclusions.

- It is impossible to significantly accelerate U.S. medium/long-term growth by means such as short-term consumer stimuluses. It is only possible to accelerate the U.S.’s medium/long term growth, as with every other major economy, by an increase in the percentage of the economy used for net fixed capital formation.

- The present level of fixed investment in the U.S. economy locks it into slow growth of only slightly above 2% a year – very substantially below China’s 5.0%.

- The U.S. can attempt to slow China’s economy towards the U.S. own slower growth rate, but it has no means to compel China to do so – that is it cannot “murder” China (as it did earlier with Germany. Japan and the Asian Tigers, for a detailed analysis of this earlier U.S. competitive success see “So-Called “Peak China” Is Simply a Western Campaign for China to Commit Economic Suicide”).

- If the U.S. cannot slow China’s economy the only way the U.S. can close the gap on China’s growth rate is by accelerating its own growth. This, however, requires an increase in the percentage of net fixed capital formation in the U.S. economy and, therefore, the U.S. must find sources of financing for this.

- U.S. use of capital from abroad to finance its own investment is a useful supplement to U.S. domestic capital creation, but it is simply not quantitatively nearly enough to be a substitute for U.S. domestic capital creation/savings in terms of accelerating U.S. economic growth.

- Trump’s tariff policy itself is incoherent and cannot produce a major increase in U.S. economic growth.

- Only a significant reduction in the proportion of the U.S. economy devoted to consumption, in order to increase the percentage used for investment, can increase the U.S. economic growth rate. Political developments which will take place in the U.S., with their consequent geopolitical implications, will therefore be deeply impacted by the forms these attempts to bring about reductions of the percentage of consumption in the U.S. economy will take.

- There are reforms which the U.S. could undertake which would release large resources from consumption to investment without any reduction in the proportion of the U.S. economy devoted to the population’s living standards. These are, most importantly, in terms of scale, reduction in the proportion of the economy devoted to military spending and/or rationalisation of the extraordinarily inefficient U.S. health system. Trump, of course, will not undertake either of these – because they would require, in the case of reducing military spending, a much less aggressive U.S. foreign policy and, in the case of health, the tackling of powerful vested interests in the U.S. which Trump has shown no sign of willingness to confront.

- As Trump will not cut military spending, or tackle the inefficiency of the U.S. health system, therefore, to attempt to speed up the U.S. economy he has no choice but to attempt to reduce the proportion of the U.S. economy that is used to maintain U.S. living standards. That is Trump will attack the living standards of the mass of the U.S. population, creating political resistance to this.

- These issues, therefore, determine the objective character of the political struggle in the U.S.. This, naturally, in this period is not between socialism and capitalism but between majpr reforms and maximisation of the means of U.S. military aggression. This development of this domestic situation in the U.S. will have major geopolitical implications. Maintenance of the present situation of the U.S., with low growth, will lead to mounting social and political tensions in the U.S. itself.

- Seen from a geopolitical angle, what this means is that an attack is being launched by Trump on U.S. living standards in order to maintain high U.S. military spending and its accompanying aggressive international imperialist policy. If Trump is successful in reducing the proportion of the U.S. economy used for U.S. living standards this will increase the ease with which he can increase U.S. military expenditure. Successful defence of U.S. living standards, conversely, will increase the pressure to reduce such U.S. military expenditure and actions. Other countries, threatened by the U.S., therefore have a direct interest in successful defence by the U.S. population against the attacks on its living standards that will be launched by Trump.

These are the fundamental conclusions which flow from an analysis of the real situation of the U.S. economy and the interrelation of this with politics and geopolitics. They make clear why Trump’s tariff policies, as announced on 2 April, cannot solve the fundamental problems that face the U.S. economy. And that the fundamental goal of Trump is to impose a severe defeat on the U.S. population, to crash its living standards, in order to better attack China.

Appendix – technical explanation of why any method other than increasing the percentage of net fixed capital formation in U.S. GDP will not succeed in accelerating underlying U.S. economic growth

Purely theoretically, expressed purely in algebra, it might appear that it is possibly to substantially increase U.S. GDP growth by means other than increasing capital investment. This is because, expressed in terms of growth accounting, the formula for GDP growth is:

GDP growth = CK+ CL + CTFP

Where, CK = contribution to GDP growth of increase in capital (capital services), CL = contribution to GDP growth of labour inputs (increase in labour hours plus improvement in labour quality), CTFP = contribution to GDP growth of total factor productivity. But once actual numbers are put it in becomes clear that only an increase in capital inputs will in practice secure a major increase in U.S. GDP growth. This is because.

- The increase in capital inputs is both the biggest contributor to U.S. GDP growth, accounting for 58% of growth, and has an ultra-high correlation with GDP growth of 0.95. That is, an increase in capital inputs will both make a high contribution to U.S. GDP growth and has an extremely high degree of certainty of doing so.

- Increase in labour inputs are the second highest contributor to U.S. GDP growth, accounting for 33% of growth, but have only a moderate/low correlation with GDP growth – 0.51. This means that the degree of certainty of increases in labour inputs leading to an increase in GDP growth is only moderate/low and the contribution of any increase in labour inputs to GDP is much lower than capital inputs.

- Increases in TFP have a moderate correlation with U.S. GDP growth, of 0.63%, but their contribution to GDP growth is extremely low, accounting for only 9% of U.S. GDP growth. Therefore increases in TFP have only a moderate chance of increasing U.S. GDP growth and, even if these occurred they would, due to the small role played by TFP in U.S. GDP growth, lead to only to a small increase in U.S. GDP growth.

Therefore, in practice, only increase in capital inputs have both a high degree of certainty and will make a high contribution, to U.S. GDP growth.

The detailed data on these correlations with and contributions to U.S.GDP growth may be found in “Trump 2.0 and China – Part 1, the real situation of the U.S. economy”.

Some readers may be surprised to see that TFP makes such a small contribution to U.S. GDP growth. This is because, very unfortunately, analysis in some sections of China’s media has failed to keep up with modern developments in growth accounting which have corrected errors made in Solow’s original formulation of this. For a detailed account of these see 中国经济增长核算法要与时俱进.

This article originally appeared in Chinese at Guancha.cn.

[i] It should be noted that in national account terms investment which has to be financed by savings/capital creation is both fixed investment, which is considered here, plus changes in inventories. However changes in inventories are much too small to offset the very large proportion of the economy constituted by fixed investment – the percentage of U.S. GDP accounted for by changes in inventories in 1965 was 1.2% of GDP and in 2024 it was 0.2% of GDP.

[ii] To understand why. By definition, the Balance of Payments must balance. Therefore, ignoring errors and omissions

Current Account (CA) + Capital and Financial Account (KA) = 0

Consequently

CA = −KA

Therefore, a current account deficit (negative CA) implies an exactly equal capital/financial account surplus (positive KA), meaning net capital inflows. Similarly a current account surplus means exactly equal net capital outflows.