The Biden presidency will probably change some of the Trump administration’s tactics towards China. But Biden will not change the underlying anti-China policies of the US openly launched under Trump. The most probable variant is that a Biden administration will try to persuade a number of countries to enter a ‘broad anti-China front’ – instead of the narrow ‘America first’ tactics of Trump. Consequently, China will find itself engaged in an international struggle between its ‘win-win’ approach to international policy and the US’s attempted ‘anti-China’ policy.

In many parts of the world the outcome of this can already be foreseen. ASEAN and most Asian developing countries, with the exception of India, will refuse to be drawn into a conflictual relation with China and will continue to seek mutually beneficial economic relations with it – a process continued in the recent signing of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). The same will apply to most of Africa, the Middle East and Russia.

At the other extreme, in the short term it will almost certainly be impossible to reverse the current anti-China positions of the majority of the US political establishment – it is an illusion to believe that the efforts of China’s English language mass media will be sufficient to prevent this, and therefore it is necessary to envisage that the struggle over public opinion within the US will be long and difficult. The US is also able to make threats against its closest allies, such as the UK, Canada, Australia and Japan, which will allow it to control the main parameters of their international policy – although in Japan and Australia this is highly irrational from the point of view of their direct economic interests.

This international situation necessarily means there are two main parts of the world in which the outcome of the struggle between China’s ‘win-win’ approach and the US’s anti-China is not yet clear – these are in the European Union, which requires a separate article, and in Latin America which is the subject of this article.

The end of Latin America as simply the US’s ‘backyard’

For many decades the United States both thought of and treated Latin America as its ‘backyard’ – exercising a dominant political and economic pressure which was backed up by numerous invasions, coup d’etats, and client dictatorships.

Because, for such a long period, the US did in reality control the situation in Latin America it would not be unfair to say that knowledge in China of Latin America was not as widespread as with some other regions of the world. The notable exception to this was Cuba – where the warmest relations, and high mutual respect, have existed for a long period between the Chinese and the Cuban leaderships.

In September 1960 Cuba was the first country in Latin America to establish diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China – after the success of the revolution led by Fidel Castro. The continuing high regard of China’s leadership for Castro was clearly expressed when he died in 2016 with Xi Jiping’s official statement declaring: ‘Fidel Castro, founder of the Communist Party of Cuba and Cuba’s socialist cause, is a great leader of the Cuban people. He has devoted all his life to the Cuban people’s great cause of struggle for national liberation, safeguarding state sovereignty and building socialism….

‘The death of Comrade Fidel Castro is a great loss to the Cuban and Latin American people. The Cuban and Latin American people lost an excellent son, and the Chinese people lost a close comrade and sincere friend. His glorious image and great achievements will go down in history…

‘The great Comrade Fidel Castro will be remembered forever.’

Xi Jinping personally visited the Cuban Embassy to pay his respects on the death of the Cuban leader.

Fidel Castro similarly expressed the highest support for China: ‘If you want to talk about socialism, let us not forget what socialism achieved in China. At one time it was the land of hunger, poverty, disasters. Today there is none of that… China is a socialist country… And they insist that they have introduced all the necessary reforms in order to motivate national development and to continue seeking the objectives of socialism.’

Castro noted: ‘The significant thing, the extraordinary thing for me and for the world, is that the legendary China, one of the first and richest civilizations and the most populated country on Earth, less than a century ago was a territory occupied and cruelly exploited by the powers imperial of that time…

“The Chinese process counted… with the contributions of great and brilliant political thinkers, who continued to develop and enrich the doctrines of socialism. ‘China has objectively become the most promising hope and the best example for all Third World countries.’

Regarding Xi Jinping Fidel Castro stated: ‘Xi Jinping is one of the strongest and most capable revolutionary leaders I have met in my life.’

The post 1998 situation in Latin America

But despite the success of Cuba’s socialist revolution in 1959 for several decades the US still continued to dominate the situation in Latin America – maintaining pro-US regimes in most countries in the continent, including installing a series of pro-US dictatorships, and supporting the terrorist war against Nicaragua after its 1979 revolution which eventually in 1990 brought down the nationally independent Sandinista government in that country.

This overall situation in Latin America, however, began to change sharply after 1998 with the election of Hugo Chavez as Venezuela’s president. Chavez successfully won numerous elections in that country until his death in 2013, and in particular defeated an attempted pro-US coup in 2002. Chavez’s success was then followed by the election of governments independent of the US in a whole series of Latin American countries – Bolivia, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Honduras, Nicaragua and others. This was the famous ‘pink tide’ in Latin America. As a consequence, from a situation whereby in 1998 the US dominated most of Latin America, for the first time in the continent’s history by 2014 the great bulk of Latin America had governments which were independent of the US and which were seeking regional cooperation.

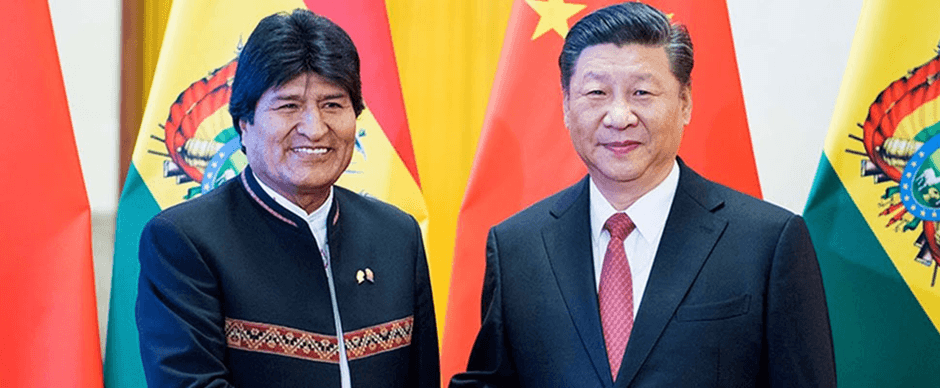

But as is well known, however, after 2014 the US then succeeded in reinstalling governments favourable to itself in a series of Latin American countries via ‘hard’ coups, ‘soft’ coups, elections or a combination of these. Pro-US regimes were reinstalled in Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, Honduras, Chile and other countries. The most recent step in this shift was the November 2019 coup d’etat in Bolivia against President Evo Morales.

But complacent US confidence that it was once again turning Latin America into its ‘backyard’ turned out to be false. Forces which supported national independence, and in some cases socialism, had strengthened and had deep roots in Latin America. Attempts by the US to overthrow the independent governments of Venezuela and Nicaragua failed, a left-wing president of Mexico Andrés Manuel López Obrador was elected in 2018, and a new left-wing government was elected in Argentina 2019. In the most recent, and spectacular, development the coup regime in Bolivia was defeated in the presidential election of October 2019 and Luis Arce, a supporter of Evo Morales and the Movement for Socialism (MAS) was elected president. In the same month, a national referendum in Chile overturned the old right-wing constitution. Simultaneously pro-US forces continued to hold power in major Latin American countries such as Brazil and Colombia. In summary both forces supporting national independence, and in some cases socialism, and pro-US forces are strong in Latin America.

It is in this situation, therefore, that China’s policy towards Latin America is formulated.

China has created major trade links with Latin America

A key change since the period when Latin America was the US backyard is that over the past two decades China has emerged as one of the most important markets for Latin American countries – in an important number of cases overtaking the US as their main trading partner. For example, in 2019, 32 percent of Chile’s exports went to China, 29 percent of Peru’s, 28 percent of Brazil’s, 27 percent of Uruguay’s, and 10 percent of Argentina’s. This mutually beneficial trade of China and Latin America has meant that despite changes in regimes already noted, Latin American governments of different ideological types, and different overall international alignments, have not attempted to disrupt this economic relationship with China. For example, during his campaign for the Brazilian presidency Jair Bolsonaro flirted with Taiwan separatists. But once he was in office, the objective imperatives of the situation made any economic break with China, or challenging of the One China policy, impossible. Far too much remains at stake. In November 2019, Bolsonaro met with Chinese President Xi Jinping, who said that China and Brazil will increase their trade ‘on an equal footing.’ Tsung-Che Chang of the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Brazil conceded in September 2020 that there are ‘many barriers’ for Bolsonaro to break with Beijing. Brazil simply does not have the room for manoeuvre that Australia, for example, has, since Australia—reliant upon the Chinese market—nonetheless joined with the US in a military alliance against China known as The Quad (along with India and Japan).

Latin American countries seek investment links with China

In addition to trade China’s investment in Latin America has been increasing significantly. Recent examples include a $2.3 billion investment by China Ocean Shipping Company in a shipping port in Peru; $3.9 billion in construction contracts to build a major highway and modernize railroads in Argentina; and a $3.5 billion deal by China’s State Grid Corporation to buy a controlling stake in Brazil’s third biggest electric utility. Mexico’s integrated supply chains with the United States and Canada have also attracted China investments in automobile manufacturing.

Given this foreign investment by China Latin American countries have begun to actively seek to attract it and have also supported China’s Belt and Road Initiative – Latin American governments from both right and left see the BRI as simultaneously mutually beneficial and free of political interference. A few examples illustrate this.

Mexico’s Minister of Economy Graciela Márquez Colín, has declared, ‘China and Mexico have to walk together, to build a stronger and more solid relationship.’ In July 2020, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement went into force. But Márquez Colín declared that despite this agreement, Mexico must ‘redouble its efforts’ to draw investment from other places, such as China.

Zhu Qingqiao, China’s ambassador to Mexico, said that his country agrees, and has ‘many plans to invest in Mexico,’ including the $600 million needed by the state-owned Dos Bocas petroleum refinery in Tabasco; this was to be financed together by the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, the Bank of China, and other international partners.

On June 4, 2019, just after he arrived in Mexico City, Ambassador Zhu wrote an opinion piece in a leading financial newspaper, El Financiero. ‘The trade war,’ he wrote, ‘will not stop China’s development. Faced with risks and challenges, China has the confidence to face them and turn them into opportunities.’ He stated China is prepared to increase its interaction with other countries, both through investments into those countries—such as Mexico—or by welcoming investment into China. China, he wrote, is not the author of this ‘trade war,’ and China would like this conflict to end.

In September 2020, Luz María de la Mora, a senior official in Mexico’s Ministry of Economy, said that China is a ‘great example’ for Mexico. China, she said, is a ‘partner to boost our economic recovery’ and help Mexico ‘emerge from the pandemic as soon as possible.’ No doubt the United States is and will be for a long time Mexico’s largest trading partner; but the new affinity between China and Mexico, particularly because of next year’s anticipated economic growth in China, is also important. Despite pressure from Washington, and there is no indication of a major change when Joe Biden becomes president in 2021, these Latin American countries such as Mexico know that they cannot break with China; that would be reckless.

Similarly in Bolivia, after the election victory of Luis Arce’s MAS, Chinese President Xi sent the new president a message of congratulations. In this, President Xi recalled the 2018 strategic partnership agreed upon by the Chinese government and then President Evo Morales. That partnership led to the choice of China’s Xinjiang TBEA Group to hold a 49 percent stake in a planned joint venture with Bolivia’s state lithium company YLB. President Morales said at the signing ceremony: “Why China? There’s a guaranteed market in China for battery production,”. Bolivia’s new president Arce was Morales’ head of economic policy. He has signaled that he would continue the policy of cooperation with China.

Regarding investment in Peru, Aluminum Corporation of China Limited (Chinalco) is investing in a $1.3 billion expansion of the Toromocho copper mine. COSCO SHIPPING Ports Limited plans to build and operate a $3 billion port on Peru’s Pacific coast. The China Railway Engineering Corporation plans to build a port in the southern city of Ilo, in a crucial copper mining region. And a subsidiary of the Zhongrong Xinda Group Co., Ltd. is building a $2.5 billion iron ore mine known as the Pampa de Pongo project. In April 2020, China announced Peru would sign a memorandum of understanding to join the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s multibillion-dollar global infrastructure program—despite warnings from Washington.

US pressure on Latin America

The dramatic increase in China’s economic ties with Latin America has been paralleled in accompanying political shifts. In addition to the countries seeking trade and investment with China already noted, at the most official level even three of the few remaining Latin American countries that previously had official relations with Taipei have abandoned this and now observe the One China policy – Panama, the Dominican Republic, and El Salvador. Confronted with this shift towards China in Latin America the US has become increasingly directly threatening to countries in the region. Again, some examples will illustrate this situation.

In September 2019, Trump’s daughter Ivanka visited Argentina. She travelled to Jujuy, which is toward the border with Bolivia. Ivanka Trump came with John Sullivan (then deputy secretary of state) and other members of the US government (from the Defense Department and from USAID). She met in Purmamarca with Jujuy Governor Gerardo Morales, and then alongside David Bohigian of the US government’s Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) announced $400 million toward road construction along what is known as the ‘lithium route’ (Argentina, with Bolivia and Chile, form the ‘lithium triangle’). This was widely seen across the border in Bolivia as a statement against the MAS’s orientation toward China.

Bohigian transitioned OPIC into its current incarnation as the International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) and launched a project América Crece (Growth in the Americas). This was directly designed as a challenge to Chinese investment in Latin America and the Caribbean. In September 2020, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo was in Guyana, where he championed the investment of ExxonMobil and other oil companies into the South American country. Pompeo said that Guyana should make a deal with US oil companies, which—he claimed—are not corrupt; ‘You look at that,’ Pompeo said in reference to their record, ‘and then look at what China does’, implying that Chinese firms are corrupt and that a country like Guyana should shun China.

On April 26, 2019, Kimberly Breier, the assistant secretary for the Office of Western Hemisphere Affairs in the US State Department, made a full-fledged attack on Chinese investment in Latin America and the Caribbean. China, she said, came to the continent with ‘bags of cash and false promises’ – she made allegations, but did not back these up with any facts.

Panama

One of the most dramatic examples of the US attempt to exert anti-China pressure on Latin American countries was in Panama. When Panama shifted its diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China in June 2017 then-President Juan Carlos Varela declared: ‘China has the largest population in the world, has the second-largest economy, [and] is the second-main user of the Panama Canal.’

Varela also said he gave the Trump administration about an hour’s notice of Panama’s decision to join China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

‘This is our decision,’ he said. ‘And I’m pretty sure I did the right thing for our people.’

‘The Trump administration soon made it clear it had a different view. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo visited Panama in late 2018 and warned against what he called China’s ‘predatory economic activity.’

El Salvador

A similar example of US pressure against national sovereignty is El Salvador. On August 20, 2018, El Salvador’s president Salvador Sánchez Cerén announced on national television that his country would break its ties with Taipei and recognize the People’s Republic of China. This was in accord with international law, said Sánchez Cerén, and it would bring ‘great benefits for our country.’

Not long after, US Senator Marco Rubio took to Twitter to announce that this move ‘will cause real harm to relationship with US including their role in “Alliance for Prosperity.”’

The ‘Alliance for Prosperity’ referred to former US president Barack Obama’s deal with several Central American countries to provide some modest development aid in exchange for a strengthened police force and the prevention of transit of migrants toward the United States; this was border enforcement dressed up as development.

Rubio’s threats however were inconsequential; the money was too little, and the price paid by the populations of Central America was too steep.

In November 2018, Sánchez Cerén went to Beijing, where he met with Chinese President Xi Jinping. Trade relations were central to the discussion, including encouragement for El Salvador to participate in China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

A year later, in December 2019, Sánchez Cerén’s successor, Nayib Bukele, arrived in Beijing to reaffirm the ties between El Salvador and China, as well as the desire of his cenre-right government to develop Belt and Road projects.

Therefore, it did not seem to matter if the president of El Salvador was from the right or the left; both were eager to acknowledge the importance of China’s role in the region, and both were willing to act independently of the US.

As news of the Chinese deals were announced, Bukele was criticized for getting El Salvador into a ‘debt trap.’ He responded firmly on Twitter. ‘What part of “non-refundable” do you not understand?’ he asked, referring to the fact that China was giving El Salvador grants and not loans.

But US pressure was not over. On January 30, 2020, Bukele stood beside Adam Boehler, the head of the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), to sign an agreement to implement ‘Growth in the Americas’ in his country.

En route back to El Salvador from China in December, Bukele stopped in Tokyo, where then-prime minister Shinzo Abe warned him not to allow Chinese companies to invest in La Unión port. China’s Asia Pacific Xuan Hoa Investment Company had been in talks to invest a considerable amount of money in the port.

The US government had campaigned against this, and now Abe whispered the United States’ warning into Bukele’s ear. The chill of the tensions between Washington and Beijing stopped Bukele’s hand; it was inevitable that he would seek to placate the United States as far as possible without breaking with China.

‘Growth in the Americas’

A key instrument used for this US pressure is América Crece ‘Growth in the Americas’. This was launched in 2018. The US likes to claim China is not transparent with its deals, but there is almost no information available on ‘Growth in the Americas’.

The US State Department website says the program ‘seeks to catalyze private-sector investment in infrastructure in Latin America and the Caribbean.’ The US government will doubtless operate to open doors for US companies.

In October 2018, the US Congress passed the Better Utilization of Investment Leading to Development (BUILD) Act, which joined the Overseas Private Investment Corporation and the Development Credit Authority into the DFC. US President Donald Trump placed Boehler – Jared Kushner’s former roommate – as its head.

The budget for the agency is US$60 billion. Both Democrats and Republicans are committed to this anti-China agenda.

One of the main DFC projects in El Salvador is the construction of a natural-gas plant in Acajutla, which is owned by the US energy firm Invenergy and its Salvadoran subsidiary Energía del Pacífico. US Ambassador Ronald Johnson said the DFC would provide financing for the project (it will be about $1 billion).

But severe concerns have been raised in El Salvador about the lack of concern for the environmental impact of the plant as well as the subsea pipeline’s effect on marine life and on the coastal habitat. But this threat to the environment is not the only one. Other attacks range up to murder of those opposed to such projects.

Ugliness of Growth in the Americas

‘Growth in the Americas’ funds have been promised in Honduras to build the Jilamito hydroelectric plant. On August 13 2020, US Representative Ilhan Omar and 27 other representatives wrote a letter to Boehler in which they pointed out that the project ‘has met a sustained campaign of opposition from affected local communities since it was announced.’ A campaign of assassinations and abductions has been carried out against opponents of the project. A lawyer for the communities concerned by the effects of this project, Carlos Hernández, was assassinated in April 2018, after the attacks that killed an activist Ramón Fiallos in January 2018. In late July 2020, armed men entered the home of Sneider Centeno in Triunfo de la Cruz and abducted him. They did the same to three other leaders of the Garífuna community.

The Belt and Road initiative

As was already noted the Belt and Road initiative is attractive to Latin American countries – China plans to spend at least $1 trillion on this project. Part of the Chinese money comes, as Bukele wrote when he left Beijing, as grants.

But this aid by China to countries that are part of the Belt and Road irks Washington. David Malpass, US undersecretary for international affairs, said in February 2018 that the US faced a serious challenge from ‘China’s non-market activities’.

In particular China invests and provides grants, Malpass said, with no insistence that the recipient countries ‘improve’ their ‘macroeconomic policies’. In other words, China does not make it a condition for such loans that labour laws are undermined or that subsidies for health and education are cut (as the IMF and the US Treasury Department often do); nor does China privilege the private sector. These are the ‘non-market activities.’

In a recent article, Professor Sun Hongbo of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences wrote that the US government pressures Latin American countries to cooperate with the US global policy agenda so that these countries – such as El Salvador – would have to choose between Beijing and Washington. No such pressure comes from China, wrote Sun.

This is a view echoed in Latin American and Caribbean capitals; they face pressure from Washington to break ties with China, something loathsome to most of the countries, as it has been for El Salvador’s Bukele. In summary what the US is doing is pressuring Latin American countries to inflict significant damage on their own economies, which benefit from ‘win-win’ relations with China, in order to pursue a US anti-China agenda.

Opposition to what the US is doing

This fact that the US is putting pressure on Latin American countries to act against their own national interests, and that of their populations, is producing a shift in public opinion in Latin America against the US and in favour of China. For example, a Pew survey from 2019 shows that 50 percent of Mexicans have a favorable opinion of China, while only 36 percent have a favourable opinion of the United States; more Mexicans had a favourable opinion of President Xi than of President Trump.

Brookings Institute, a strongly pro-US, institution published a report in July 2020 which noted: ‘Today, comparatively speaking, the current state of U.S.-LAC [Latin America and the Caribbean] relations looks remarkably bleak. After three years of the Trump administration, the United States is practically displaced, largely absent, or has reverted to type as the threatening hegemon, prompting major declines in LAC favorable opinions toward Washington and a renewal of “Yanqui go home” antagonism. Trump has dramatically reversed course on a host of well-established policies from trade (withdrawal from TPP [TransPacific Partnership], for example) and migration to climate change and development assistance. His administration reclaimed and expanded strong-arm tactics and punitive sanctions against leftist regimes in Venezuela, Bolivia, and Cuba, and revived the interventionist rhetoric of the Monroe Doctrine of two centuries ago. While Congress has stepped in to ameliorate some of the damage, for example on development aid and renegotiation of NAFTA [North American Free Trade Agreement], the blow to the U.S. image is real. In the face of China’s assertive commercial and soft power diplomacy, these hardball tactics are playing directly into the hands of Beijing and anti-U.S. constituencies in the LAC region. In the COVID-19 response, China seems to have done a better job in rushing medical supplies to more states in showy displays of solidarity and friendship (except, of course, to countries that still recognize Taiwan).’ This situation in Latin America is in contrast to the situation in the advanced economies.

Increased understanding in Latin America of the importance of China

In addition to a more widespread grasp in Latin America of the importance of relations with China, a particularly acute grasp of this exists in countries seeking to maintain national independence. This was well expressed in a speech by prominent Bolvian journalist Ollie Vargas in a speech to a ‘Peace Forum’ organised by the ‘No Cold War’ campaign in September. This speech was given after the pro-US coup in Bolivia in November 2019 to remove President Evo Morales, and before the victory of Luis Arce, a Morales supporter and former economy minister, in the presidential election of October 2020. Again, it is worth quoting at length as an example of views developing in Latin America in light of present trends.

‘Bolivia is the latest country [after the November 2019 pro-US coup] to have suffered US intervention, to have left the path of sovereignty and national development and adopt the US model of free market destruction and colonial dependency. What has happened in Bolivia is what the US wants to impose in China, in Cuba and in those countries that have successfully resisted US imperialism for so many years…

‘In the economy, the effects have been… disastrous. After just a few months of neoliberal reforms: paralyzing state-led development projects started under Evo Morales; privatising the state industries that were nationalised by Evo Morales; and destroying the levels of public and social spending that were possible thanks to the socialist development that Bolivia had enjoyed in the past 14 years. All of that has been destroyed. Unemployment has now tripled, poverty has risen to the levels it was 15 or 20 years ago when Bolivia was the poorest country in the region.

‘Bolivia has gone back to the path of dependency, of assuming its role in a global division of labour in which the country exports raw materials with no means to alleviate the poverty that the country suffers.

Vargas noted:

‘China stands as an inspiration for countries in Latin America and the global south. China is a country that has refused to accept its destiny as a colonised country. China is a country that suffered a century of humiliation, a country whose big cities were divided up between numerous colonial powers for many years.

‘What’s happened in China now? China has refused to accept that position and has taken the path of national development through using the state as the motor through which it builds the country’s productive forces and through that lift people out of indignity, out of poverty, give people the tools with which to live a human life with internet, with electricity, with running water, with homes that don’t collapse whenever there is rain. And that’s the path that countries such as Bolivia were also taking for 14 years – beginning to develop and which has since been destroyed.

‘The China model is an inspiration for countries around the world. It’s important to remember that China is not a country that seeks to impose its model around the world; it doesn’t seek to invade countries, promote coups, to install puppets around the world. Here in Latin America China has extremely close relations with both Venezuela and Columbia – two countries with completely different, divergent official ideologies. But China still has commercial ties in both countries. China had commercial ties with Argentina’s right wing, neo-liberal government of Mauricio Macri and next door here in Bolivia with the government of Evo Morales. China doesn’t seek to impose their way of life, their culture, their economic model on those it interacts with.

‘Although the China model isn’t something that is being exported, it’s something that we have to study because it’s the model that can bring peace around the world. If the United States engaged with the world, if it sought partners in development, if the United States sought to work with countries as equals then the world would be a far more peaceful place. If they did as China does, cooperating with countries for mutual economic benefit, for mutual economic development, then the world would know prosperity, the world would know peace.

Vargas concluded regarding the potential win-win relations of Bolivia and China:

Here in Bolivia, China was involved in a number of state development projects which brought huge benefits to Bolivia people. The internet connection with which I’m speaking to right now is thanks to Bolivia-China cooperation under the government of Evo Morales. Before Evo Morales, Bolivia had a neoliberal model which created poverty and the country had almost no connectivity. Those in rural areas and working class areas of the city didn’t have phone signals or internet connection. And what happened when Evo Morales took power? He worked with China to build a satellite, it’s called the Tupac Katari satellite, named after an Indigenous leader who fought the Spanish Empire here in Bolivia. Bolivia is a small country, it doesn’t have the expertise to launch a rocket into space, so it worked with China to launch the satellite which now provides internet and phone signal to all corners of the country, from the Amazon, through to the Andes, and here in the working class areas of the big cities.

‘From this example of cooperation we can learn a lot because although China brought the expertise and a lot of the investment, they didn’t seek to take ownership of the final product. That satellite belongs to Bolivia, it belongs to the Bolivian people and China entered into that project as a partner, as an equal for mutual economic benefit.

‘Is that the model the US adopts? It’s not. The US seeks to take ownership of the country’s natural resources, seeks to take ownership of a country’s government and that model will always lead to war because it overrules the right of self-determination of the people. So wherever the people demand to govern themselves, demand national independence and sovereignty, they always run up against the model that seeks to crush them.

‘I think we have a lot to learn from the way that China interacts with the world on peaceful terms, seeking equal partners, seeking cooperation rather than domination, rather than dependency.

‘China is an inspiration for countries like Bolivia, an inspiration for how to rise out of a position of undignified poverty and of colonial dependency. We have a lot to learn. To summarise, while China is rightly maintaining economic and political relations with all Latin American countries regardless of their political ideology, a number, which is increasing in size, of forces in Latin are very actively seeking increased relations with China. A number of these, while not mechanically copying China, are seeking to learn from its model of development. This is aided by the fact that, on the political field, China has firmly indicated in numerous diplomatic forums that it opposes all external attempts to interfere in Latin America’s internal affairs – including attempts to promote ‘regime change’ in countries such as Cuba and Venezuela. China, and also Russia, have openly spoken out against the US unilateral sanctions against Venezuela.

Conclusion

The broad historical trend of development in Latin America, as well as current developments, is therefore clear from these facts. From a situation where for a century almost all Latin American countries were subordinate to the US, and a number remain so, an increasing number are seeking national independence – and a few are seeking a socialist path of development. Mutually beneficial relations with China interact with and aids this.

China does not interfere in the internal affairs of Latin American countries, and, as already analysed, seeks to maintain good relations with all Latin American countries regardless of their political orientation. Nevertheless, the fact that an increasing number of Latin American countries are seeking to maintain national independence strengthens their relations with China. Furthermore, while China does not attempt to persuade any country to follow its socialist path nevertheless, of course, other countries can study China and draw lessons for their own experience.

For China, as well as Latin American countries, the mutual advantages are clear. Latin America is a market of 650 million people. It has a large number of developing countries in which China’s manufactured exports are highly competitive. China also has the expertise and companies capable of building infrastructure, helping develop the raw material and agricultural production on which many Latin American countries still depend, and has the expertise to allow Latin American countries to proceed to their own manufacturing. At the same time friendly countries block aggressive US attacks on China in the UN and elsewhere. As already noted China is, with the European Union, the area of the world in which potentially the most countries are choosing between the ‘win-win’ approach offered by China and the economically damaging path of anti-China subordination to the US proposed by the latter.

Given the importance of these developments it is of considerable international importance for China to pay great attention to developments within Latin America. 07 December 2020

By John Ross, Senior Fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies Renmin University of China.

And Vijay Prashad, Director Tricontinental Institute for Social Research and Non-Resident Senior Fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies Renmin University of China.

* * *

This article was originally published in Chinese at Guancha.cn.