In particular, as usual, neo-liberals avoid dealing with the facts. They suggest that to avoid the ‘middle income trap’ China should follow the policies advocated by the World Bank and IMF – known internationally as the ‘Washington Consensus’ and which Justin Yifu Lin refers to as ‘Western mainstream development theory.’ But as Lin entirely accurately notes factually of this Washington Consensus: ‘I have not seen a developing economy implement Western mainstream development theory with success. The few examples of superior development performance… are the result of implementation of policies which from the perspective of mainstream economic theory are wrong.’

More precisely, as was noted in November 2015 from the Counsellors Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China: ‘Lin believes that over 20 years has passed and the countries that have promoted personalization, marketization and liberalization based on neo-liberalism have not been successful. Instead, they have experienced economic meltdown or stagnation and continuous crises and their average economic growth rates are even lower than the structuralism era in the 60s and 70s, with crises happening more frequently than in the 60s and 70s.’

Which economies have achieved rapid development

The present author would have some terminological differences with Lin, as there were always alternative development theories to the Washington Consensus in the West, and even more importantly China’s economic reform deriving from Deng Xiaoping was still more successful – this is analysed in ‘Deng Xiaoping and John Maynard Keynes.’ But terminological issues aside Lin’s fundamental point is entirely correct factually. Indeed, as the data given below will show, the situation is even worse than Lin indicated. The majority of countries which have followed the ‘Washington Consensus’ have become more ‘undeveloped’ in relative terms – that is they have actually fallen further behind the most advanced economies.

As confirmed by the data below, only an extremely small number of developing countries have achieved sustained rapid economic growth and/or made the breakthrough from ‘low’ or ‘medium’ income to ‘high income’ status. However, the fact that all the economies which have achieved this most rapid growth are in Asia makes it easy for China to study them.

This fact that so few developing countries have achieved sustained rapid growth, and made the transition to ‘high income’ status, necessarily has the corollary that the overwhelming majority of developing countries have failed in this – and therefore that the neo-liberal Washington Consensus, which was dominant outside Asia, has been factually shown to fail as a development theory. Instead of studying a failed theory the method of ‘seek truth from facts’ therefore requires that:

- the focus from a positive perspective should be on analysing those few developing countries which have achieved very rapid economic growth and become high income economies;

- from the negative perspective an analysis should be made of why those countries which followed the World Bank/IMF Washington consensus failed to achieve rapid economic growth and make a successful transition to high income status.

The aim of this article, therefore, is to establish the actual international facts on economic growth achieved by developing economies. Such a factual study naturally leads to theoretical conclusions. However, the method of ‘seek truth from facts’ is the only correct one not only for China but all countries. Factually demonstrating factually which development strategies have been successful and which have not is the indispensable prerequisite for any theory. A theory must correspond to the facts; the facts cannot be ignored or altered to fit a (false) theory. If any theory fails to fit the facts, it is wrong and should be abandoned.

This has crucial practical significance for China. China can no more escape the laws of economics than any other country. If China bases policy on a factually false theory of how to make the transition to a high income economy it will fail – with negative consequences for over a billion people in China and halting China’s national rejuvenation. Therefore, establishing the facts of success and failure in developing economies is a prerequisite for judging theories which explain them.

What is a high income country?

As a preliminary aside, it should be noted that there is a significant discussion as to whether the ‘middle income trap’ actually exists. For example, reviewing the issue, The Economist concluded regarding the middle income trap: ‘Some of its proponents argue that middle-income countries typically grow more slowly than richer and poorer economies. That is claptrap. If anything, they grow faster… from 1950 to 2010… Economies with an income per head of $13,000-14,000 (at purchasing-power parity) achieved per-person growth of almost 2.9% over the next ten years on average. That is faster than the average for any other income level… Development is a long and arduous process, during which economies continuously evolve in scope as well as size. Potential traps lurk at every level of income. There is no reason to single out the middle levels.’

However, this dispute will be disregarded here. It will be demonstrated that it is extremely difficult for a developing country to break through to high income status. Therefore, the issue will be treated as a factual examination of why only an extremely small group of countries have undergone very rapid economic development and broken out of low or medium economy status and become high income economies.

What is a high income economy?

A first issue is evidently what is the criteria for an economy to become ‘high income’? Internationally there are 68 countries or regions of countries which meet the World Bank official definition of a ‘high income’ economy – a per capita GDP of $12,736. This, however, presents a significantly misleadingly favourable picture for drawing lessons for China for two major reasons.

- First, the majority of these 68 high income economies are in very small countries – 35 out of 68 have populations of under five million. Only 22 high income economies or regions have populations of more than 10 million.

- A number of countries have ‘high income’ status exclusively due to their simultaneously having very small populations and being havens for tax evaders (Cayman Islands, Monaco, Liechtenstein, Bermuda, Isle of Man, etc.) or due to possession of large quantities of the single commodity oil (Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates etc).

Evidently neither of these types of economy can provide a development model for China – which has neither a small population, nor a strategy based on being a haven for tax dodgers, nor is an essentially oil dominated economy. Such realities, however, demonstrate that the method sometimes followed in media discussions of looking at China’s ‘ranking’ in a list of countries which takes no account of population, economic size, or whether a country’s economy is essentially exclusively an oil exporter is extremely misleading. Such a serious issue as China achieving high income status cannot be dealt with on the basis of sloppy statistics but instead requires accurate information.

Which countries have achieved high income status?

Turning to the facts of economic development, the most important ‘high income’ economies have been so for many decades (UK, US, Germany, France etc.). They achieved this status by relatively slow growth over many decades – usually more than a century. For example, average annual per capita GDP growth over the entire 20th century was only 1.9% in the US, 1.8% in Germany and 1.5% in the UK. Evidently such a slow growth path cannot provide a model for China – which aims to achieve ‘moderate prosperity’ by 2020 and ‘high income’ status by international standards in the next 5-10 years.

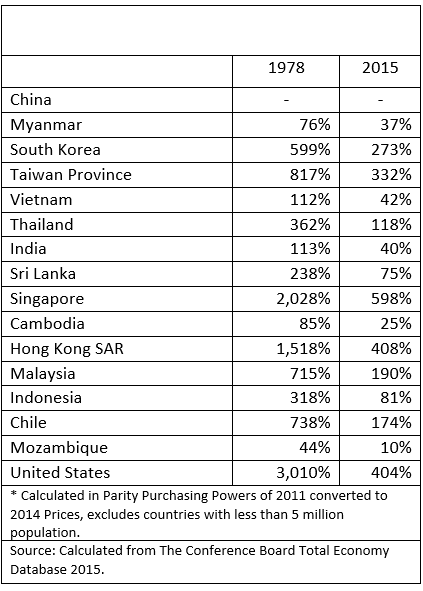

Turning to the conditions facing China’s development in the period since it began ‘reform and opening up’ in 1978, it can be noted that the majority of large developing economies actually fell further behind the US in this period. Taking as a criterion a country having a population of at least five million, and 40% of US per capita GDP in 1978, then of the 53 economies in this category 28 fell further behind the US in per capita GDP in 1978-2015 and 25 improved their position in comparison to the US. The majority of large developing economies therefore ‘undeveloped’ relative to the US in this period. This emphasises the difficulty of sustained rapid economic growth.

Over a longer period, it should also be noted that a number of previously advanced economies fell back into the ranks of developing economies or suffered disastrous setbacks. For example, Argentina’s per capita GDP fell from 67% of that of the US in 1938 to 30% by 2015, Chile’s per capita GDP fell from 60% of the US in 1910 to 50% by 2015, Russia’s per capita GDP fell from 43% of the US level in 1975 to 28% by 2015.1

It is also particularly striking that of countries that have gained in per capita GDP compared to the US only a few have gained greatly. Since the beginning of China’s economic reforms in 1978 only six countries or regions with a population of at least five million have closed the gap on the per capita GDP of the US by at least 20% – Mainland China, Malaysia, Taiwan Province of China, Hong Kong SAR, Singapore, and South Korea. All six are in Asia. Of these Mainland China achieved the fastest per capita GDP growth of any country not only in 1978-2015 but over the total period 1950-2015. Four of these economies – the ‘Asian Tigers’ of South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan Province of China, and Hong Kong SAR – all starting from a far higher per capita GDP than Mainland China, have already achieved China’s goal of transition from a ‘low’ or ‘medium’ to a ‘high’ income economy.

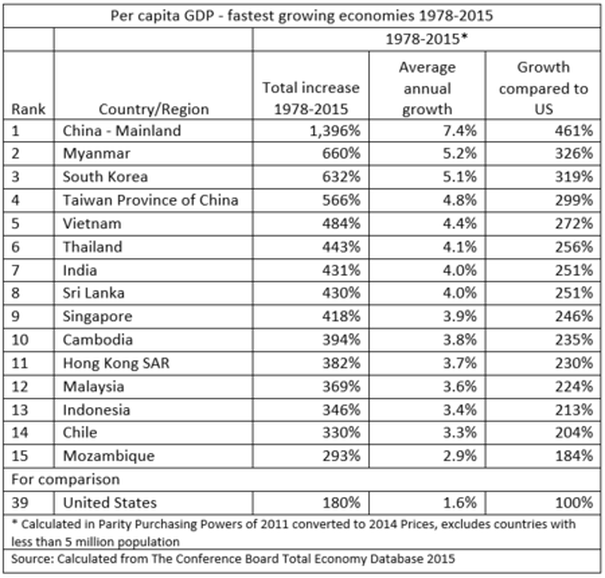

Asia’s dominance in rapid growth economies is overwhelming. As Table 1 shows all 10 of the world’s fastest growing economics are Asian – indeed the top 13 are. It is therefore Asian economic development, not the Washington Consensus of the World Bank and IMF, which has been an overwhelming success. It follows that what China has to study to ensure it breaks through to high income status is not the dogmas of the World Bank but the forces which led to China’s own economy outgrowing all others and, after that, what forces produced rapid economic growth in Asia.

China and the ‘Asian Tigers’

If China’s per capita GDP has grown more rapidly than any other economy, why has it not yet achieved ‘high income’ status by international standards? The answer, of course, lies in the difference in the starting points of different economies.

China in 1929 was already one of the world’s least developed countries, with a per capita GDP only 8% of the US – at that time India’s per capita GDP was 30% higher than China’s. This was a testimony to the failure of both the Qing dynasty and the post-1911 Republic to produce economic development capable of catching up with the advanced economies – China’s per capita GDP had been 13% of the US in 1900 and 10% in 1913. By 1950, after invasion by Japan and civil war, China was almost the world’s poorest country with a per capita GDP only 5% of the US. In 1950 of 141 economies in the world for which data can be calculated only 10 countries – eight in Africa (Botswana, Burundi, Ethiopia, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Lesotho, Malawi, Tanzania) and two in Asia (Myanmar, Mongolia) – had lower per capita GDP’s than China.2

To give a comparison on the calculations of Maddison India’s per capita GDP in 1950 was almost 40% higher than China’s and on the latest calculations of the Conference Board it was 80% higher. By 1978 China’s had outstanding social achievements, shown in the fastest increase in life expectancy in any major country in world history. China had also laid the basis for industrialisation and greatly narrowed the lead in per capita GDP of the other very large developing economy, India, which had existed in 1949. By 1978, compared to 1950, India’s lead in capita GDP over China had been reduced from 80% to 30% based on Conference Board PPPs, and from 40% to zero on Maddison’s calculations. These were very considerable economic achievements, and the social ones were absolutely outstanding, but China’s per capita GDP was still far behind that of other rapidly growing economies.

Since 1978 China has shown the world’s fastest economic growth, rapidly closing the gap in per capita GDP with all advanced and fast growing economies. As shown in Table 2 in 1978 US per capita GDP was 30 times that of US while by 2015 this gap had been closed to four times. As also shown China has closed the gap on, or overtaken, all other rapidly growing developing economies – in many cases dramatically. Nevertheless, the far higher per capita GDP starting point of the ‘Asian Tiger’ economies explains why they have already achieved ‘high income’ status by international criteria, while this is still 5-10 years ahead for China. Taking each ‘Asian Tiger’ since 1978:

- Mainland China has closed the gap on Taiwan Province’s per capital GDP from over eight times to only slightly over three times.

- Mainland China has closed the gap on Hong Kong SAR from Hong Kong’s per capita GDP being 15 times Mainland China’s to four times.

- China has reduced the gap from Singapore’s per capita GDP from being over 20 times Mainland China’s to being less than six times.

- Mainland China has closed the gap on South Korea from South Korea’s per capita GDP being almost six times Mainland China’s to under three times;

In summary, since 1978 China’s economy has far outperformed the ‘Asian Tigers.’ Nevertheless, the ‘Asian Tigers’ themselves have continued to grow much rapidly than the established advanced economies, and consequently for China to finally close the per capita GDP gap with the Asian Tigers China must continue to outperform them for a prolonged period – several decades.

China – comparison with advanced economies

Finally, so far China has primarily been compared to rapidly growing developing economies. However, it also casts a clear light on China’s development strategy to make a comparison with advanced economies.

It was noted earlier that the most important advanced economies achieved that status by very slow per capita GDP growth, of under two percent a year, over very prolonged periods – typically more than a century. Table 3 shows that this fundamental model has not changed. Taking the most important advanced economies over the period 1978-2015, annual average per capita GDP growth was 1.7% in the UK, 1.6% in the US, Germany and Japan, and 1.2% in France. China’s growth was approximately five times as fast as all these economies. The result was China’s catch up in terms of per capita GDP. It may also be clearly noted that the major advanced economies all had essentially the same per capita GDP growth rate of under two per cent – the maximum being 1.7% and the minimum 1.2%. As a result, over the period 1978-2015:

- China closed the gap in per capita GDP compared to the US from US per capita GDP being 30 times China’s to being four times.

- China closed the gap in per capita GDP compared to Germany from Germany’s per capita GDP being 26 times China’s to under three and a half times.

- China closed the gap in per capita GDP gap compared to the UK from 21 times to under three times.

- China closed the per capita GDP gap compared to France from 25 times to under three times.

- China closed the per capita gap Japan from slightly under 21 times to under three times.

This rapid catch up by China has a clear corollary and also historical context. The very slow growth rates of the advanced economies is not a new phenomenon but has existed throughout their entire history – including when they had per capita GDPs which were only a fraction of their present ones. The average slow growth of advanced economies is therefore not due to their current high levels of per capita GDP but existed also at an earlier stage, when they had levels of per capita GDP comparable to or even significantly below China’s present one. As all the advanced economies have had essentially the same, and very low, growth rates for over a century if China adopts their growth model it will also have low growth.

Conclusion

The global facts of economic development are therefore clear. Any economic theory and strategy for breaking through the ‘middle income trap’ must therefore correspond to these facts. It may be seen:

- Any model based on copying advanced economies is erroneous if the aim is to catch up with the advanced economies. The model of the main advanced economies is based on slow growth maintained over very many decades – over a century. China using such a slow growth model could not achieve ‘high income’ status by international standards in 5-10 years or close the gap with the advanced economies. China must therefore use economic methods which have been shown to generate rapid growth – those used by successful developing economies.

Of these methods used by developing economies:

- China’s has been by far the most successful strategy in generating rapid economic growth. China’s rate of per capita GDP increase has outperformed all other economies both over the entire period 1950-2015 and in 1978-2015. An examination of the superiority of China’s economic theory compared to Western analysis has been made in ‘Deng Xiaoping and John Maynard Keynes.’

- The second most successful economic development strategy after China’s has been what is generally referred to as the ‘Asian development model’ – the main features of this Asian model are analysed in ‘Why Adam Smith’s ‘classical theory’ correctly explained Asia’s growth – and how this clarifies why Paul Krugman’s critique of Asian growth failed to predict events.’

- The neo-liberal Washington Consensus of the World Bank and IMF, has been a failure compared both to China’s development model and those of the rapidly growing Asian economies – precisely as was noted by Justin Yifu Lin.

These are the facts on which any theory and policy for China’s economic development must be based including for overcoming the ‘middle income trap’. All three of these fundamental facts regarding of global economic growth must be explained by any economic theory and development strategy. They obviously lead to three decisive questions.

- Why did China outperform all other economies in per capita GDP growth?

- Why did a small number of Asian economies not perform as well as China but nevertheless outperformed all other developing economies and in some cases, aided by their starting points, have already achieved high income status?

- Why did most developing economies, those that followed the Washington Consensus, fail to achieve rapid economic growth, or make the breakthrough to high income status, and indeed in the majority of cases actually fell farther behind the most advanced economies?

Any policies for China’s economic development must be based not on dogma’s of the Washington Consensus, which global growth data shows has failed as a development strategy, but on the facts of those countries which have achieved successful rapid economic development. As always the only correct method in dealing with such a serious question as how to overcome the ‘middle income trap’ is to ‘seek truth from facts’.