The UK political crisis, with the loss by Theresa May’s government of its parliamentary majority, coming only a year after the economically irrational referendum vote for Brexit and resignation of Prime Minister Cameron, is less globally decisive than US political instability but an important factor in European politics and strikingly confirms the crisis in the main ‘Anglo-Saxon’ countries.

This US/UK political crisis has major lessons. Because these ‘Anglo-Saxon’ countries were the ones in which neo-liberal policies were most famously implemented. The fact that deepening political instability has broken out in the two major countries where neo-liberal policies were inaugurated by their most famous representatives, Reagan and Thatcher, is evidently not accidental. However, while numerous analyses have been made of the economic aspects of neo-liberalism less attention has been paid to the present clear demonstration of its dangerously destabilising political consequences. This article therefore analyses in detail the relation between the economics of neo-liberalism and the deepening US/UK political destabilisation.

But, in addition to analysis of immediate events, it must be borne in mind that the UK and US were successively for two centuries the world’s most powerful economies. Analysing the deepening political crisis in the Anglo-Saxon countries, in its fundamental historical context, therefore also allows a clear understanding of the present dynamics of the global economy and geopolitics – as well as making clear why US domestic instability is inextricably linked with international geopolitical instability.

Historical position of the Anglo-Saxon economies

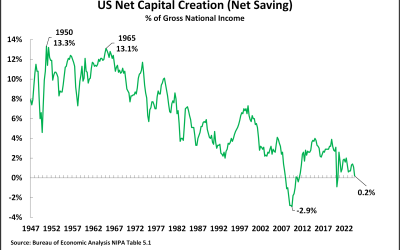

Starting with the fundamental historical framework, during the two centuries in which the ‘Anglo Saxon’ economies, first the UK and then the US, were the dominant countries in the world economy they both, at the respective peaks of their power, played a decisive global role in stabilizing the world economy through being large scale suppliers of capital for economic development of other economies.

The economic process involved, and its relation to the geopolitical dominance of first the UK and then the US, was simple. Throughout most of this period the UK and US were the world’s most internationally competitive economies. This competitiveness generated large balance of payments surpluses from overseas trade and property incomes. But, in economic terms, a balance of payments surplus necessarily involves an equal export of capital. Therefore, this high competitiveness of the US and UK economies generated balance of payments surpluses, which were used to generate capital exports to other countries, which in turn helped stabilise recipient states and the global economy as a whole. While this essential mechanism was the same in both countries certain specific features of the two economies will now be briefly examined in chronological order.

Pax Britannica

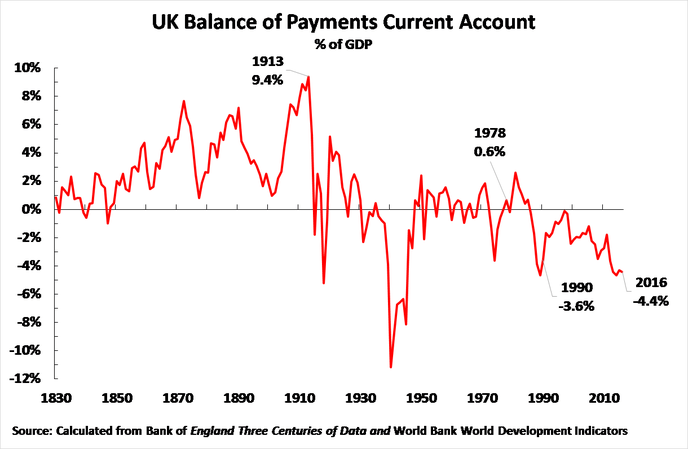

The period of UK global economic dominance in the 19th and early 20th centuries was classically studied in Imlah’s masterpiece Economic Elements in the Pax Britannica. This analysed the way in which throughout most of the 19th century large scale capital exports from the UK stabilised the world economy and geopolitical situation. Imlah’s study was of the detailed economic background to the reality that general conflict between the great European powers, which for most of this period were also the world’s most powerful states, did not occur for almost a century between the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 and the beginning of World War I in 1914. Imlah noted that throughout this century the UK, at that time the world’s most powerful economy, was a large-scale exporter of capital – Figure 1 shows this process and extends the data to the present day.

Figure 1 shows that huge UK export of capital, generated by its balance of payments surpluses, already reached eight percent of GDP by 1870 and by 1913 it was approaching 10% of GDP – to understand the consequences of the trends in this chart, as already noted. it should be appreciated that running a balance of payments surplus is equal to exporting capital.

Imlah noted that massive supply of UK capital to other states, by compensating for shortage of capital in them, stabilised both the individual recipient countries and the world economy. It was for this reason that Imlah termed the 19th century the ‘Pax Britannica’ – supply of capital to the other countries by the world’s most powerful economy of that period stabilised the global situation. This period of avoidance of generalised conflict between the major European powers in 1815-1914 was, of course, used by them to colonise other countries – but that is another issue.

But after 1913, as Figure 1 shows, the economically devastating consequences of World War I for Britain meant that the UK could no longer play its former global stabilising role. By 1928 British export of capital had fallen to 2.6% of GDP. Britain’s ability to stabilise the global economy was then further weakened by the Great Depression – by 1935 UK export of capital was only 0.5% of GDP. During World War II the UK became a massive recipient of capital in aid from abroad – above all from the US.

After World War II UK export of capital resumed, but only at around of one percent of GDP. By this time also the UK had so declined as a percentage of the world economy that its capital exports were too small to play a globally stabilising goal.

Britain moved briefly into balance of payments deficit in the mid-1970s but then from the early 1980s onwards the UK moved into a permanent and worsening balance of payments deficit – this deficit indicating its economy had lost its international competivity. This date of the severe deterioration of Britain’s international competitiveness is of course significant – it was the Thatcher period.

This UK balance of payments deficit from the early 1980s had great domestic economic significance as analysed below. However, in terms of its global consequences by the late 20th/early 21st centuries the UK had lost its position as an economic ‘superpower’. While the UK balance of payments deficit was still internationally significant, being the world’s second largest in dollar terms after the US as shown below, by this time the global role of the UK deficit was very subsidiary compared to the US.

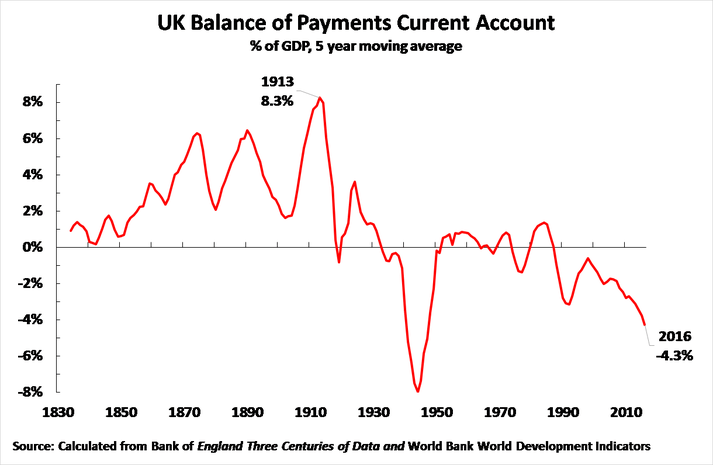

To avoid the UK data being dominated by purely short-term movements, and therefore to allow the trend to be seen clearly, a five-year moving average of the UK balance of payments is shown in Figure 2. As may be seen after 1913 the UK never regained its position as a massive exporter of capital and therefore lost its ability to stabilise the world economy. This role passed to the other great Anglo-Saxon power, the US – which is analysed in the next section.

Rise and decline of the US stabilising role in the world economy

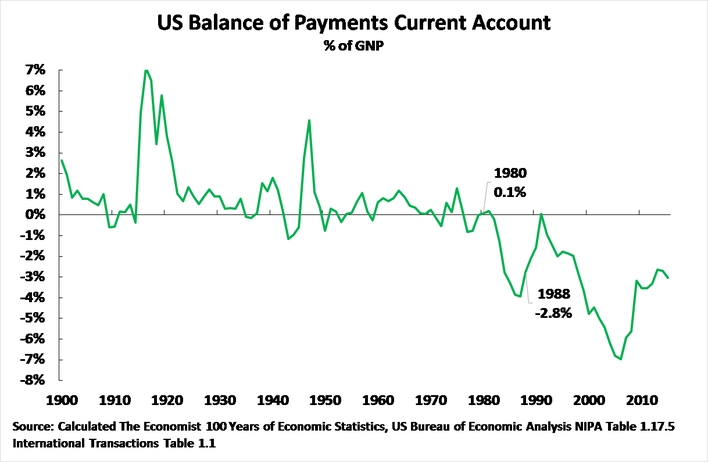

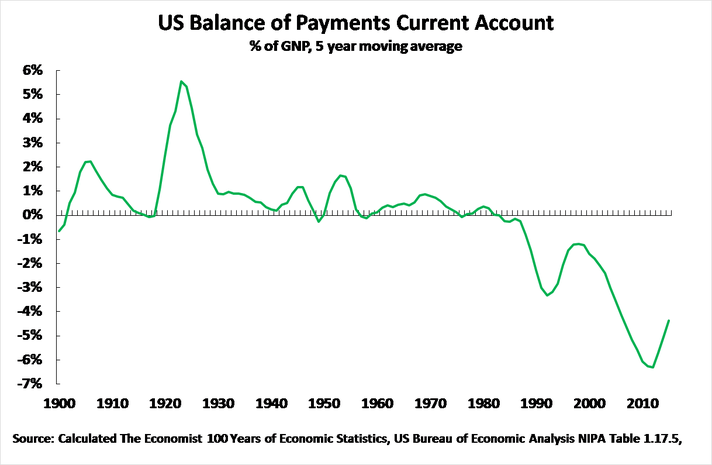

The US became world’s largest economy in approximately the 1880s but there was naturally a time lag before its period of global economic dominance began. In the 19th century the US had been a large-scale capital importer – a major part of which came from the UK. However, by the beginning of the 20th century the US economy’s rising power meant it had become a capital exporter – see Figure 3. The US remained an exporter of capital until the beginning of the 1980s. As the gigantic export of capital by the US during the World Wars, reaching its peak at 7% of GNP, was exceptional a five-year moving average for this data is also shown in Figure 4.

After 1945 the US acquired hegemony among the capitalist economies – completely replacing the UK. US capital exports were important not only in general but also specifically for particular regions and countries US foreign policy wished to stabilise/aid. For example, the US granted massive economic aid to Western Europe after World War II (the Marshall Plan), the US gave large scale aid to key military allies (e.g. Israel), the US subsidised numerous countries in the ‘Third World’ it wished to support US foreign policy, US company investment into numerous economies stabilised recipient states etc.

As with the UK during the ‘Pax Britannica’, from World War II until the 1980s the US could use large scale capital exports to maintain the stability of global order in which it was the dominant economy. These capital exports, in turn, were made possible by the US balance of payment surplus – reflecting the US’s high degree of international competitiveness.

However, Figure 3 shows that from the early 1980s a fundamental change took place. The US moved from balance of payment surplus into balance of payments deficit – that is the high international competitiveness of the US had disappeared. From a balance of payments surplus in 1980 the US had moved to a deficit of 2.8% of GDP by 1988 – an annual deficit of over $400 billion in today’s prices.

The date of this sharp decline in US international competitiveness is of course significant as it is the period in which Reagan was president. It is equally extremely striking that the US moved into balance of payments deficit, that is the international competitiveness of its economy declined, at exact the same time as the UK – in the 1980s. The leaders of the US and UK during this fundamental decline in economic competitiveness being, of course, Reagan and Thatcher.

This worsening of the international competitive position of the US and UK would necessarily lead to deterioration of their domestic and global positions – the trends which are analysed below are merely the precise mechanisms by which the deteriorating international competitive positions of the US and UK worked themselves out. The present political destabilisation of the US and UK will be seen to be an inevitable consequence of these fundamental economic processes.

The Anglo-Saxon economic ‘black hole’

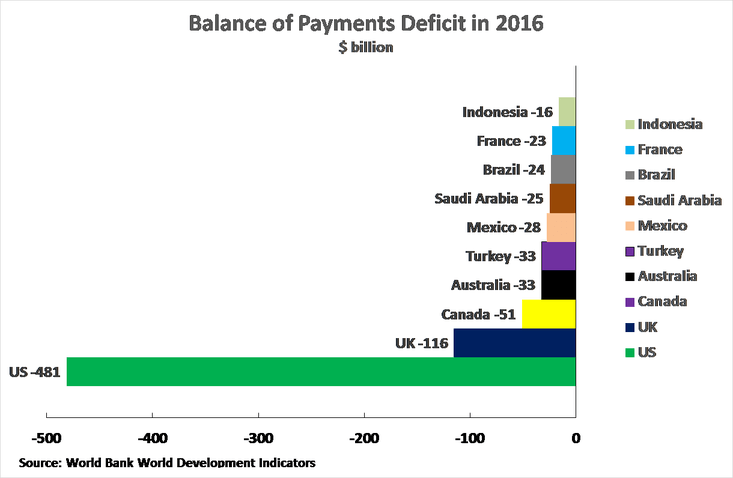

The net effect of the huge decline in US and the UK international competitiveness under Reagan and Thatcher, with both the US and UK moving into large balance of payments deficits, was that the major Anglo-Saxon economies became a type of global economic ‘black hole’. This may be seen clearly in Figure 5 which shows the 10 economies in the world with the largest balance of payments deficits in 2016. No other country even comes close to the $481 billion balance of payments deficit of the US or the $116 billion deficit of the UK.

This movement of the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ economies from balance of payments surplus to balance of payments deficit, that is from being suppliers of capital to requiring large amounts of capital from the rest of the world, necessarily changed their entire role in the world economy. From the UK and US position in the 19th and most of the 20th centuries, of being large scale suppliers of capital to the rest of the global economy, the US and UK by becoming dependent on capital from other countries reversed their role to becoming a ‘black hole’ in the world economy. From being globally stabilising exporters of capital the US and UK became dependent on capital from other countries. This meant that the US and UK have been transformed from stabilisers of other countries’ economies to destabilising the world economy.

As the impact of the US under Reagan was globally most important this will be concentrated on. But it will be seen that Thatcherism was simply a small scale variant of Reaganism – naturally with certain specific national features.

Decline of US international competitiveness

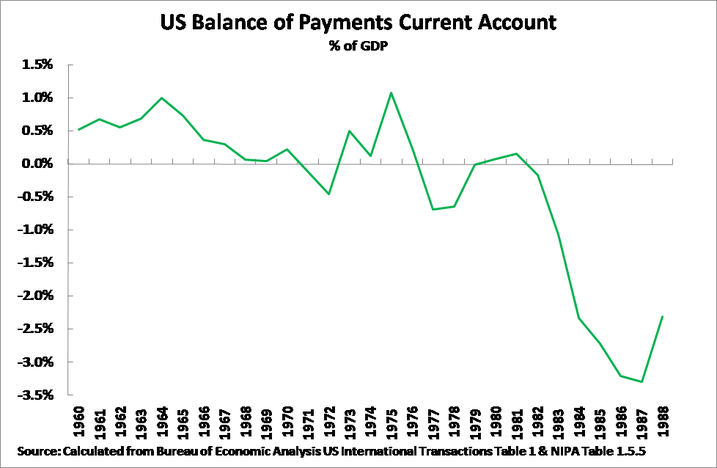

Analysing first the international dimension of the US economy, It was already noted above that the Reagan period witnessed a radical decline in US international competitiveness. As shown in greater detail in Figure 6, prior to Reagan winning the presidency in 1980 the US balance of payments, the key indicator of the US economy’s competitiveness, had remained essentially in balance despite the negative impact of the international oil price rise in 1973 – the largest US balance of payments deficit was 0.7% of GDP in 1977. In contrast, following Reagan’s election the US balance of payments deteriorated sharply – i.e. the US economy suffered from rapidly declining international competitiveness. By 1987, Reagan’s penultimate year in office, the US balance of payments deficit reached 3.3% of GDP – showing unprecedented post-World War II worsening US competitiveness. Overall in the period from 1980, the last year before Reagan came to office, and 1988, his last year in office, the US balance of payments deteriorated from a surplus of 0.1% of GDP to a deficit of 2.3% of GDP – a worsening of 2.4% of GDP, or almost $450 billion at today’s prices.

This sharp decline in US international competitiveness under Reagan, and the creation of a large US trade/balance of payments defict, necessarily had major consequences for the domestic economic structure of the US and US political stability which logically culminated in the Trump period. As a higher proportion of US goods were imported, due to the widening balance of payments deficit, jobs were lost in the US in industries which had previously produced for the home market those products which were now imported. This created the beginning of the notorious phenomenon of the US ‘rust belt’ – whole regions of the country characterised by shut down industries and unemployment. These ‘rust belt’ regions voted for Trump in 2016. However, before analysing these political consequences, a decisive feature of the Reagan period, in addition to loss of international competitiveness, will be examined – Reagan’s commencement of the massive build up of US debt.

Reagan and the accumulation of US debt

The declining international competitiveness of the US economy illustrated in Figure 6 shows that from Reagan onwards the US became increasingly dependent on inflows of capital from abroad – i.e. on external sources of capital. Figure 7 however shows that Reagan also simultaneously commenced large scale US domestic borrowing and debt build up .

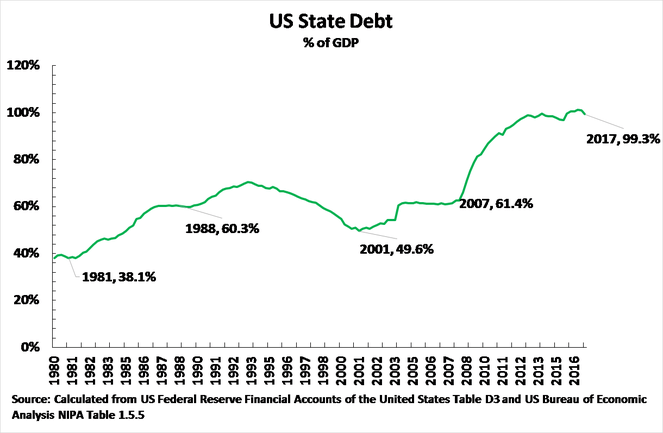

US state debt sharply increased from 38% of GDP when Reagan became president to 60% of GDP when he left office. While in mere words Reagan talked about ‘small government’ in reality a policy of high state spending, focussed on the military, was carried out which could only be financed by debt. In summary, the area in which the Reagan showed real economic skill was large scale borrowing and debt accumulation.

Once again Reagan created a policy framework which was then followed by most subsequent US presidents. Initially Clinton, reversing Reagan’s policy, reduced US state debt to 50% of GDP, but George W Bush rapidly restored US state debt to Reagan’s levels – state debt reaching 61% of GDP by 2007 as shown in Figure 7. With the beginning of the international financial crisis US state debt then rose rapidly further – reaching 99% of GDP in the 1st quarter of 2017.

This data therefore shows clearly that large scale build-up of US state debt was begun under Reagan, not simply during the international financial crisis – although the latter of course augmented US state debt further.

Rising US household debt

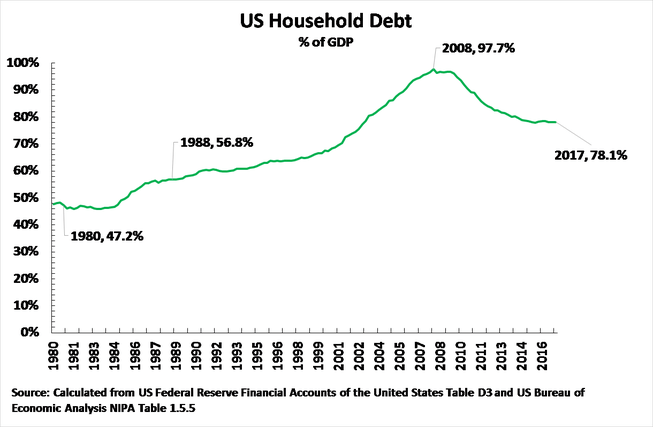

Alongside this large-scale US state borrowing the Reagan period saw a rise in US household debt – which increased from 47% of GDP in 1981 to 57% in 1988 (see Figure 8). Once again Reagan began a process which successor US presidents continued. Under Clinton, while state debt fell as a percentage of GDP, household debt continued to rise. This process continued under George W Bush – household debt reaching 98% of US GDP by 2008.

Such a large-scale build-up of US household debt was clearly unsustainable – US households were spending beyond their real incomes. The violent consequences of the international financial crisis therefore necessarily forced a sharp reduction in US household debt, with it falling from 98% of GDP in 2008 to 78% in the 1st quarter of 2017. This greatly exacerbated the fall in US living standards from levels which had been temporarily sustained by the large-scale debt increase under Reagan and his successors. This in turn necessarily destabilised US politics.

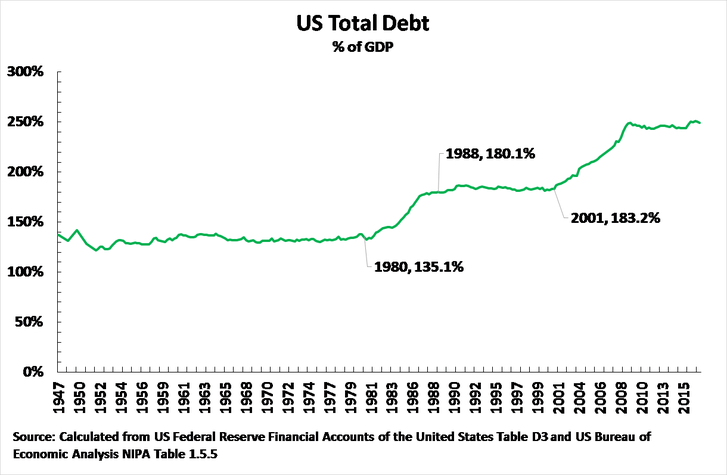

In summary, the overall consequences of the process inaugurated by Reagan was therefore a huge build-up of total US debt, which rose from 135% of GDP in 1980 to 188% in 1988. to 250% by 2009 – see Figure 9. The process unleashed by Reagan’s military spending, continued on the state side by the military expenditure of George W Bush, and on the household side under both Clinton and Bush, might therefore be likened to a huge ‘credit card binge’. While the huge bill on the credit card is being run up the card owner feels good as they are spending a lot! But when the credit card debt necessarily has to be paid the owner feels the deeply damaging effects.

The repayment became due with the international financial crisis. With the beginning of this crisis US state debt dramatically rose from 62% of GDP in 2007 to 101% of GDP by 2015, but simultaneously with this explosion of state debt the economic consequences for the population was extremely severe. Not only did US median incomes fall below 2009 levels, as analysed below, but US households were forced to run down debt by almost 19% of GDP.. With this combination of a fall in household incomes and the necessity of households running down debts accumulated from Reagan onwards, the deep economic and social discontent of the US population shown in the 2016 US elections was inevitable.

Trends in US income inequality

Turning to other features, Reagan inaugurated a massive increase in US inequality, and a falling share of total incomes received by the great majority of the US population – the consequences of which culminated in current US political instability.

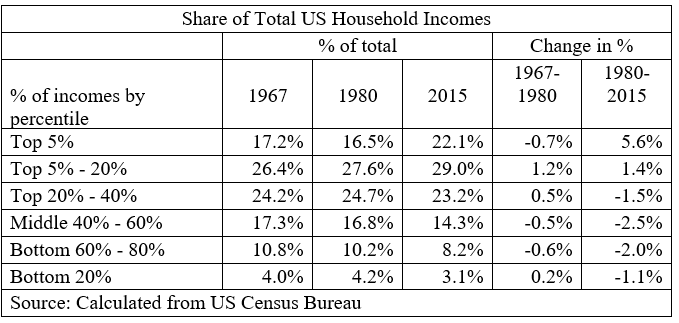

Table 1 below shows the percentages of US total incomes received by different levels of US income groups. As it will be seen that a clear change took place in 1980 the changes are shown in two periods – 1967-1980 and 1980-2015.

Analysing first the richest and poorest groups, from 1967-1980 the share of total incomes received by the 20% of American households with the lowest incomes rose marginally from 4.0% to 4.2%. The percentage of total income received by the top 5% fell from 17.2% – 16.5%. A small but definite evening out of the most extreme US income differences was therefore occurring in 1967-1980.

After 1980 this trend radically reversed. The share of incomes of the bottom 20% of US households fell from 4.2% to 3.1%. Simultaneously the share of incomes of the top 5% of US households rose by an extremely sharp 5.6% – from 16.5% to 22.1%. Furthermore, the share of total incomes in every income group in the bottom 80% of the US population declined – the total fall for 80% of the population being an extremely severe 7.1%, from 55.9% to 48.8%.

In monetary terms, the total income of the top 20% of US households in 2015 was $5.1 trillion while that of the entire bottom 80% was only $4.9 trillion. The total income of the top 5% of the US population in 2015 of $2.2 trillion was over seven times that of the bottom 20% of the US population of $0.3 trillion.

In summary, if from 1967-80 there had been some evening out of the most extreme US income inequalities, after 1980 there was instead a massive increase in the share of incomes of the top 5% of the population with and a simultaneous severe loss of the share of incomes of 80% of the population.

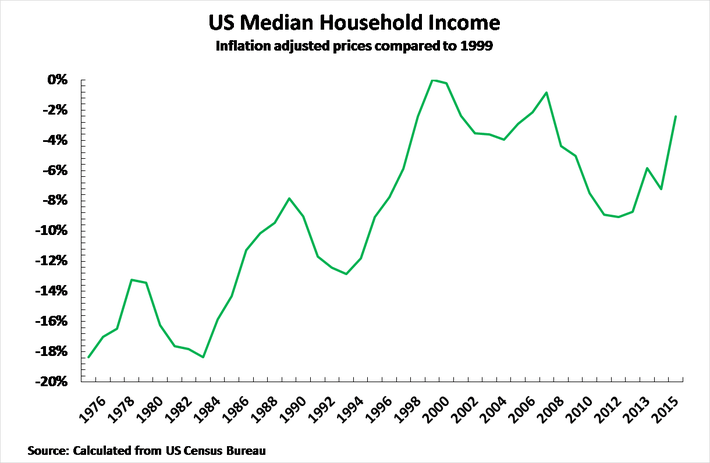

Finally, the trends after the international financial crisis undoubtedly exacerbated the trends in US inequality already established under Reagan. As Figure 10 shows US median household incomes by 2015 were still below the level of 16 years previously in 1999. At the trough of incomes in the Great Recession, in 2012, US median household incomes were more than 9% below their 1999 peak level. The US population had therefore suffered more than a decade and a half serious fall in incomes – which would produce deep political discontent and anger in any country.

Summary of US trends

The Reagan period was therefore characterised by the following features:

- A major fall in the international competitiveness of the US economy;

- The US economy losing its previous position as a large-scale exporter of capital and it becoming dependent on imports of capital;

- A very sharp increase in US state debt;·

- An increase in US household debt,

- Sharply increasing inequality

·

These fundamental trends established under Reagan were continued by his successors.

Thatcher

Data confirms that Thatcherism was essentially a smaller scale version of Reaganism – naturally with certain specific national features.

- The first fundamental parallel between Thatcherism and Reaganism was the sharp deterioration in the UK’s international competitiveness under Thatcher. This was already shown in Figure 1 above. The UK moved from a balance of payments surplus of 0.6% of GDP in 1978, the year before Thatcher came to office, to a deficit of 3.6% of GDP in 1990, the year she left office. Therefore, under Thatcher the UK balance of payments deteriorated by 4.2% of GDP. This worsening of UK international competitiveness under Thatcher was consequently even worse than the US under Reagan – the UK’s balance of payments situation deteriorating by 4.2% of GDP compared to 2.4% for the US.

- This rapid deterioration of the UK’s international competitiveness under Thatcher, the increasing proportion of products which were imported, necessarily produced the same phenomenon as the growth of the ‘rust belt’ under Reagan. In the case of the UK it was the north of England that suffered massive unemployment and closure of industries. The political destabilisation and anger produced by this began the process leading to these regions voting in favour of the economically irrational policy of Brexit as a protest.

- UK unemployment rose dramatically under Thatcher – increasing from 6% when Thatcher came to office to 12% by the mid-1980s. Under the impact of rising unemployment and regressive tax changes introduced by Thatcher UK inequality rose rapidly. The Gini coefficient went from 0.25 in 1979 to 0.34 in 1990. Under Thatcher, as under Reagan, a massive increase in proportion of income going to the better off occurred. The real income of the bottom 10% of the population fell by 2.4 per cent, so the poor were worse off in 1990 than in 1979, while the income of the top 10% of the population rose by 48%. As a result, the number of those living in poverty under Thatcher rose sharply. Taking a standard UK measure of poverty, those with incomes below 60% of median incomes before housing costs, in 1979, 13.4% of the population were in this category while by 1990 this had almost doubled to 22.2%.

Thatcher enjoyed one major advantage compared to Reagan. In the 1980s, due to the discovery of North Sea Oil, the UK became a massive oil exporter. This economic windfall, due to geography not economic innovation, became even more valuable after the huge international oil price increase of 1979. The great tax revenues from oil and gas meant that Thatcher was able to avoid the large-scale build-up of state debt which occurred under Reagan. But, as can be seen from the increasing UK balance of payments deficit in this period, despite the enormous economic windfall from North Sea oil and gas this was not used to improve the competitiveness of the UK economy – on the contrary the international competitiveness of the UK economy substantially worsened under Thatcher.

With the worsening of the competitiveness of the UK economy which had begun under Thatcher, and which continued to worsen after her, Thatcher’s successors were not able to avoid a huge debt build up. Therefore, with a certain delay, the Reagan pattern of not only worsening international competitiveness and sharply rising inequality but also a huge build up of debt was replicated in the UK – making the parallel of the economic courses launched by Reagan and Thatcher complete.

In summary, the Thatcher period, as with the Reagan period, saw:

- a massive deterioration in UK international competitiveness, and in consequence an increasing dependence of the UK economy on capital from abroad;

- an extremely rapid rise in inequality.

·

Destabilisation of US & UK domestic politics

Having analysed the key trends under Reagan and Thatcher it is abundantly clear why their policies led directly to the domestic political instability which is currently gripping the US and UK.

- The drastic loss of international competitiveness of both the US and UK economies under Reagan and Thatcher led necessarily to elimination of jobs in industries which had previously supplied the domestic market as imports replaced domestically produced products. This culminated in the creation of the ‘rust belt’ in the US, which voted for Trump in 2016, and economic depression in the North of England – which voted for Brexit in 2016.

- Inequality rose dramatically under both Reagan and Thatcher, inaugurating the trend which has deepened further since.

- Reagan immediately launched a course of massive build-up of US private and state debt and, with a certain delay, a huge debt build-up also developed in the UK.

Global destabilisation

Finally, it should be noted that in one sense Reagan and Thatcher merit being considered as fundamental turning points – in the sense that they inaugurated policies which their successors continued. The deterioration of US and UK international competitiveness which began under Reagan and Thatcher became worse under their successors. While Reagan took the US balance of payments from surplus to a maximum balance of payments deficit of 3.4% of GDP, George W Bush took the US to a maximum deficit of 6.3% of GDP. The massive US debt build-up which began under Reagan became worse in the private sector under Clinton, and worse in both private and state sectors under George W Bush. The simultaneous accumulation of state and private debt which the UK had been able to avoid under Thatcher, due to revenue from North Sea Oil, became dramatic under Blair and his successors.

The inevitable result of this domestic and international destabilisation launched by Reagan was the 2008 international financial crisis – as both US reliance on foreign sources of capital and the build up of US personal debt had become unsustainable. The resulting international financial crisis forced retrenchment on the US both internationally and domestically:

- The US balance of payments deficit contracted from 4.3% of GDP in the last quarter of 2007 to 2.4% of GDP in the 2nd quarter of 2009 – while in the 1st quarter of 2017, the latest available data, the US balance of payments deficit was 2.5% of GDP.

- US total debt stopped rising after it reached 250% of GDP in the 3rd quarter of 2009 – but the financial resources available to US households sharply contracted with debt falling from 98% of GDP at the beginning of 2008 to 78% of GDP by the 1st quarter of 2017.

·

This forced retrenchment of the US of course produced the deepest US recession since the Great Depression – and shook the entire global economy in the international financial crisis.

Geopolitical and domestic political destabilisation

The international financial crisis in turn destabilised not only US/UK domestic politics but the entire international situation. The course of increasing international political instability after 2008 is extremely clear:

- In 2010 the Arab Spring and the generalised destabilisation of the Middle East began;

- Following the collapse of Gaddafi’s Libyan regime in 2011 ‘jihadists’ were powerfully reinforced in West Africa;

- In 2012 the electoral breakthrough of Marine in Le Pen in France began the rise of ‘populist’ movements in advanced countries;

- In June 2016 the UK voted for Brexit;

- In November 2016 Trump was elected US President, against the opposition of the establishment of both Republican and Democratic Parties, inaugurating almost continual severe political clashes in US politics;

- In May 2017 Macron was elected French President against the opposition of both right and left wing traditional political parties, and then Macron proceeded to crushingly defeat the traditional French parties in the legislative elections,

- In June 2017 Theresa May lost her Parliamentary majority in UK general election.

·

In short, the course embarked on by Reagan and Thatcher culminated in the destabilisation of not only domestic but international politics. This is of course why US the domestic political turmoil around Trump has been intertwined with international geopolitical destabilisation.

Why the delay in destabilisation?

Finally, the economic policies of Reagan and Thatcher clearly explain why the temporary ‘feel good factor’ while they were in office was replaced by deepening economic and political destabilisation ever since. As noted above Reagan and Thatcher may be compared to drunken ‘credit card bingers’. While the spending spree on credit goes on the drunk feels good because of all the things they are buying on debt but while simultaneously the strength of their business, their international competitiveness, is weakened by excessive consumption. But the drunk then feels terrible when they suffer first the hangover and then the extraordinary financial hardship involved in repaying the massive debts that have been run up – and when this has to be done under conditions in which their business is now far less internationally competitive than it was previously.

The world is still paying a terrible price for the drunken credit card binge of Reagan and Thatcher and the global financial ‘black hole’ it created in the Anglo-Saxon economies. The deep political instability now wracking the US and UK is the indelible legacy of Reagan and Thatcher.

Conclusion

Numerous correct economic critiques of neo-liberalism have been published, including in China – and therefore these analyse why China must avoid its damaging consequences. But another dimension is that the deepening political destabilisation playing out in the US and the UK, the historic homes of neo-liberalism, also gives another warning of why neo-liberalism is so dangerous and damaging. China and other countries must also clearly avoid the damaging political consequences of neo-liberalism.